A Celestial Cinémathèque? or, Film Archives and Me: A Semi-Personal History

September 2014

The Royal Film Archive of Belgium, aka Cinematek.

Baby boomers who think that they lived in the best of times can find evidence in my relation to film archives. I started studying cinema in the late 1960s, when university film programs began and archives were starting to open up to university researchers. Over my forty-plus years of visits, archives have undergone many changes and confronted many challenges. (“Challenges” are what we used to call “problems.”) I feel privileged to have watched these difficulties rise and be met—the need for preservation and restoration, the debate about rescuing nitrate-based copies, the rise of home video and cable television, and the pressures of digital media. What I hope to offer in the essay that follows are some sketchy answers to questions that arise from my own, admittedly limited, encounter with the archive world.

The encounters and the questions go together. From the start of my academic life I’ve been interested in the art of the cinema. While other researchers are interested in how films reflect or influence society, or how they are part of larger institutions (studios, government agencies), I’ve tried to focus on the ways in which filmmakers’ choices of form and technique shape their material and affect viewers. Paraphrasing Ernst Gombrich, I’m interested in forms and norms.

Pursuing those questions, I’ve tried to balance intensive and extensive study. Intensively, I watch films several times, sometimes very slowly, in order to examine how cutting, framing, lighting, staging, and other techniques are deployed. Repeated viewings also help me understand a film’s overall form, the way in which it presents a narrative or some other large-scale construction. But focusing so much on single films risks missing their relation to broader traditions. Working more extensively, I’ve also tried to see films in relation to the norms of their time, their genres, or their cinematic precursors and legatees.

I suppose the closest analogy to my line of inquiry would be that of art history, where scrutiny of individual works is guided by knowledge of their relation to traditions, schools, and craft practices. Rembrandt’s paintings have their unique artistic identity, but they need to be understood in relation to the history of portraiture, the development of sfumato, and the artisanal artworld of his day. Similarly, although Hitchcock’s Rope remains powerful taken on its own, it is more fully understood in relation to developments in the thriller genre, Hitchcock’s changing conceptions of “pure cinema,” and the growing use of long takes and complex camera movement in the 1940s.

Archives, it should be obvious, provide ideal situations for both avenues of research. Intensive viewing is difficult in projection, but watching a film at a flatbed machine allows you to stop, to go back, or to watch a sequence very slowly. (Nowadays these features are available on video playback, but when I started there was no such thing.) Just as important, archives are essential for extensive viewing. In order to understand the stylistics of 1910s European cinema, for example, a trot through a few masterpieces isn’t enough. We need to look at films in bulk, some of them very ordinary and even bad, in order to understand the norms governing filmmakers’ creative choices. Archives harbor a great many uncelebrated films that can shed light on the history of cinema art. If you are asking certain questions, no film is uninteresting.

Hence, in general terms, my need to explore archives. But my personal history is interwoven with tremendous changes in film archivery. In what follows, I’ll try to suggest how my own interests have intersected with changes in film culture and moving-image technology, as those have in turn affected archives.

An economy of scarcity

For about eighty years, the study of film history was dominated by an economy of scarcity. This was partly due to the nature of the medium.

Film archives are often called film museums, for a good reason. Like a museum of the visual arts, a cinémathèque preserves, restores, and displays artifacts. A film copy is subject to the same sorts of degradation that a painting might suffer. It can be damaged through accident, and it can be changed at the will of the users. Just as a Renaissance altarpiece may be pulled down, cut up, and remounted as a free-standing painting, so a film print can be cut and rearranged by censors or exhibitors. This happened a great deal in the silent cinema, when films were adjusted for different national markets, and it still sometimes happens today. Similarly, many early films were colored in one fashion or another, but for decades the prints circulated without tinting, toning, or hand-coloring.

A film print isn’t unique the way a painting is. Since the start of cinema, films were distributed in many copies derived, ultimately, from the camera negative. Yet each print was different—sometimes slightly, sometimes strikingly—from its mates. In this respect, a film is more like a photograph or a woodblock print. The single copy, while preserving many aspects in common with its counterparts, is also subtly a thing unto itself. For example, films made in the US Technicolor process exhibit extraordinary differences from print to print. The process simply had a wide and unpredictable range of results. So the archivist must be alert for the uniqueness of every film copy.

Until very recently, the commercial market place couldn’t be counted on to preserve films adequately. Because films were circulated and shown in a rapid rhythm, and because they were regarded as ephemeral entertainments, very few production firms maintained libraries of their output. Gaumont of France and Nordisk of Denmark are rare examples of companies who saw the virtue of storing their films, and even those collections were not complete. The American companies often destroyed their back catalogues in order to save space and money. As a result, only a tiny percentage of the world’s silent film output survives today.

Hence the economy of scarcity. For decades the film industry has put its emphasis on the latest release, the current hit. And as the new release became the old one, it passed into history and became inaccessible. People who wanted to see films from earlier times were largely unable to do so. True, companies occasionally reissued films, as Hollywood did during the 1940s to meet increasing demand. And there have always been fans who collected copies and government agencies which stockpiled film material. Still, there was no systematic effort to collect films from earlier eras until the 1930s. That was when film archives were born.

Creating a canon: 1920s–1930s

Before there were institutionally stable film archives, the writing of film history relied upon journalistic accounts and writers’ memories of seeing films as they were released. For example, Léon Moussinac wrote at a period when intellectuals were starting to take serious interest in cinema. Arguing against the view that cinema was mere recording of theatre, they tried to show that the new medium was the basis of a new art. Moussinac’s Naissance du cinéma (1925), a résumé of his viewings of films playing in Paris since 1920, constructed an account of film history that relied on two concepts.

Louis Aragon and Léon Moussinac, early 1940s, prisoner camp.

First, borrowed from traditional art history, was the idea that film history could be understood as the interplay among national schools. According to Moussinac and those who followed him, the American school displayed lyricism, concentrated storytelling, and a gift for burlesque. The Swedish directors harnessed the American discoveries in order to display their national sensitivity to landscape. The Germans turned to dark fantasy and complex pictorial compositions, while the French explored inner states and poetic imagery. Each school had as well its own masters: Griffith and Ince, Sennett and Chaplin, Sjöström and Stiller, Murnau and Lang, Gance and Epstein. At the end of the 1920s, Moussinac would add the Soviet cinema to his chronicle, with Eisenstein, Pudovkin, and others its figureheads.

A second concept that Moussinac deployed was less explicit but no less influential. The history of cinema could be understood as a liberation from its theatrical origins. He argued that the Americans discovered a purely cinematic rhythm, while the French developed this in the direction of individual psychology and highly refined plastic effects.

By the mid-1930s, a general story had taken shape that was to prove enduring. Its most influential form was seen in Maurice Bardèche and Robert Brasillach’s Histoire du cinéma of 1935. They accepted the division into national schools but, with the benefit of knowing sound cinema, were able to provide a more exact period scheme. Between 1919 and 1924, they argued, cinema became an autonomous art. Bardèche and Brasillach specified what Moussinac had left vague: the liberation from theatre was accomplished through devices specific to this new medium. Close-ups, superimpositions, unusual camera angles, and above all editing gave film unique resources for storytelling. To the division into national schools Bardèche and Brasillach added another scheme, that of birth-youth-maturity. The progress in technique led filmmakers to discover, step by step, cinema’s essence, and this teleology was fulfilled by the end of the 1920s. At that point, the silent cinema had become a mature art form. Sound, Bardèche and Brasillach claimed, led to a shrinking in artistic possibilities.

Later historians, writing in French and other languages, nuanced this account of the growth of “film language,” but it wasn’t fundamentally challenged. Who could have done so? Who could have borne witness to the Japanese cinema of the 1920s and 1930s—that great cinema which was producing more features than any other country in the world? Who could have integrated into the Europeans’ historical framework the cinemas of South America and China?

The sketch of film history constructed by French writers and their successors in other countries remained the official story. Reiterated by later generations of writers, it remains a powerful tale. To this day, the triumvirate Méliès-Porter-Griffith is held to be the source of cinematic storytelling as we know it. The masterworks acclaimed by journalists in the 1910s and 1920s, from Intolerance and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari to Metropolis and La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc, form the common core of classic revivals, DVD releases, and public performances with orchestras.

Sustaining the canon: 1930s–1960s

The canon was reinforced by the emergence of film archives. When well-supported archives were launched in the mid-1930s, they took the silent fictional cinema, as opposed to documentary or experimental filmmaking, as their central concern. Many early archivists had directed ciné-clubs, where classics were among the main fare. The Brussels-based Club de l’?cran was one of many who provided the first generation of archivists. Once systematic collecting began, a great deal of effort went into finding, conserving, and screening the classics of film art acclaimed in the mainstream histories.

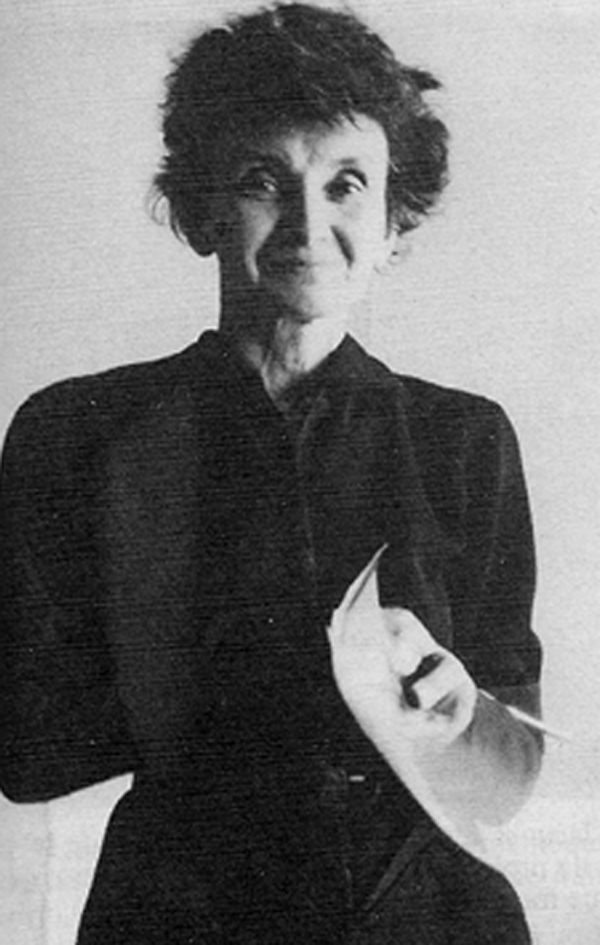

Iris Barry.

This tendency is particularly evident in the work of the Museum of Modern Art Film Library, as supervised by the curator Iris Barry. Barry knew Bardèche and Brasillach’s Histoire; she translated it into English in 1938. She had also served with the London Film Society, a major ciné-club. No surprise, then, that when creating a film collection she followed the traditional canon. MoMA quickly acquired copies of works by Méliès, Porter, Griffith, and Chaplin, as well as important German and Russian titles. In 1936 Barry and her husband John Abbott, director of MoMA, traveled to Europe to acquire copies of the most important silent and early sound films.

As the only venue in America that screened classic films regularly, the Museum became a temple to which the devout made pilgrimages. There, in just the first months of 1936 you could see Caligari, The Golem, The Love of Jeanne Ney, The Last Laugh, an installment of Fantômas, La Souriante Mme. Beudet, La Chute de la Maison Usher, and La Coquille et le Clergyman. These and many more would make their way into the MoMA circulating library of classic films on 16mm. The prints could be rented by schools, libraries, and ciné-clubs. Through these channels, the Film Library shaped Americans’ thinking and writing about film history for decades. Lewis Jacobs’ Rise of the American Film (1939) and Arthur Knight’s Liveliest Art (1957) relied chiefly on the MoMA canon.

Barry’s unit was well-funded and efficient, but it labored under constraints. Because MoMA’s remit was to collect only the best in any medium, Barry was obliged to confine herself to widely-accepted masterworks. Although the library swelled to over 700 titles, she included few items from American directors, from the French “Impressionists,” and from less well-known Soviet directors (Kuleshov, Barnet, FEKS). Other archives collected more comprehensively.

Famously, the Cinémathèque Française put the emphasis on acquisition and exhibition. Langlois gobbled up prints and showed them all, the famous and the obscure alike. The collection expanded secretly under Nazi occupation, so that after the war Langlois could launch programs filled with discoveries. And once more, archival activity shaped thinking about film history. A new generation of cinephiles was ready to overturn the classic canon.

The most famous among these critics (later to become filmmakers) were associated with the journal Cahiers du cinéma. For these young men, dreaming nightly at the Cinémathèque, all of film history was presented as a simultaneous order, Malraux’s musée imaginaire on film. An unknown Germaine Dulac film might be followed by Scarface or an early Griffith. Film criticism gained from a wider range of historical reference, a more eclectic sense of what the art of cinema might be. Now Sunrise rather than Der Letzte Mann became Murnau’s masterpiece (and for some, the greatest film of all time). Langlois’s screenings, along with the flood of overseas films into Paris following the Liberation, created a new awareness of how contemporary cinema might connect with earlier traditions. Instead of seeing the sound cinema as a steep falling-off from the glory days of silence, the Cahiers group saw it as continuing great traditions of personal expressivity and powerful mise-en-scène. The auteur policy, I think, was born partly from the effort to locate constellations in the Cinémathèque firmament.

Marie Epstein, early 1950s.

Important as the programs were in reconfiguring criticism, they did not lead to a renaissance of research into film history. Georges Sadoul, Jean Mitry, and other postwar historians were no radical revisionists. These men worked at refining the standard story of the growth of the medium in the silent era. They wrote their vast tomes on the basis of catalogues, clippings, and memories, not intensive or extensive viewing.

This was partly because the Cinémathèque Française was not geared to researchers. Langlois celebrated rare finds by screening them, not by making them available for scholarly investigation. As late as the 1970s, when I went to Paris to study obscure French films of the 1920s, local scholars were astounded that Langlois had admitted me. Whenever they had asked to watch a film in his archive, Langlois had told them to wait until it was screened in the public rotation. Yet there I was, an American sitting every day at Marie Epstein’s visionneuse. My only explanation was that Mary Meerson had told me, at my entry interview, “The French avant-garde were the first avant-garde. You will write this.” I sort of did.

Archives and Academe

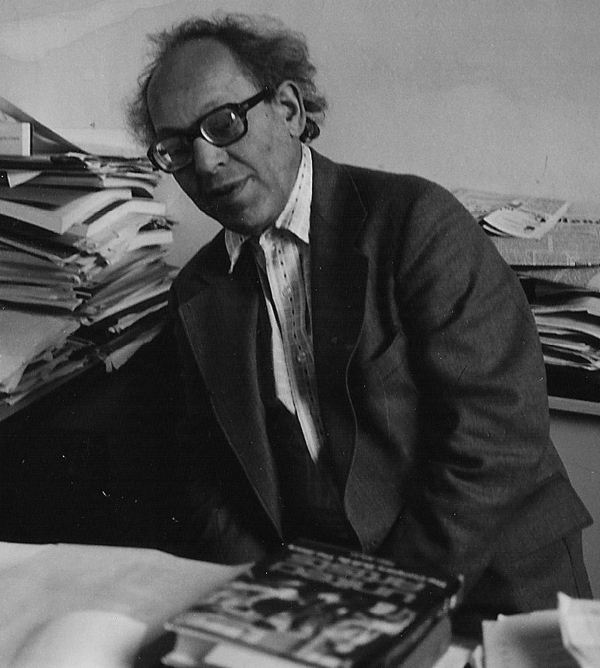

Jacques Ledoux, 1979. Photo: Kristin Thompson.

The earliest years of the Cinémathèque Royale de Belgique fitted well into the tradition I’ve been sketching. In the early 1950s, Ledoux and his colleagues screened ciné-club classics; one of the earliest shows, in 1950, was called “Les meilleurs films de tous les temps.” Programs included the famous works of Flaherty, the Soviets, Stroheim, Chaplin, Clair, and the like. But the Brussels Cinémathèque also showed recent French work by Bresson and Melville, American films by Renoir and Preston Sturges, and then-little-known Soviet silents like Protazonov’s Girl with a Hat Box. The canon was widening.

Over the same years, as new archives were founded, the International Federation of Film Archives (FIAF), established the validity of the idea of a modern, professional archive. FIAF members began systematically to coordinate the preservation and exchange of film materials. Still, though, an economy of scarcity reigned: Archives would have to cooperate in sharing the best copies and in locating undiscovered classics.

Fascinated by film as a teenager, I quickly absorbed the tastes that created the canon. I read books celebrating the great silent films and the major studio pictures of the 1930s and 1940s. I bought an 8mm copy of the Odessa Steps sequence and projected it on my bedroom wall. At college, I revived a ciné-club whose programs derived from the MoMA circulating program. My first screening was Der Blaue Engel. (Unfortunately, the sound went out on our projector halfway through, so our audience had a chance to test von Sternberg’s belief in cinema as the music of light.) These were the mid-1960s, so of course we also screened recent releases from Godard, Kurosawa, and other auteurs. When I saw Mizoguchi’s Sansho the Bailiff, I decided I wanted to study cinema for the rest of my life.

My timing was lucky, because archives were becoming more user-friendly. For one thing, FIAF began to recognize the importance of cooperating with researchers. In 1971, Karen Jones of the Danish Film Archive and Eileen Bowser of MoMA founded the indispensable International Index to Film Periodicals, and a year later, the first Symposium of FIAF’s annual congress was devoted to “Film Archives and Historical Research.”

Meanwhile, the “new cinemas” of the period were calling attention to filmmaking nations that had previously been considered marginal. South American movements like Brazil’s Cinema Nôvo, Eastern European young cinemas, and the Japanese New Wave could not be ignored. Films from the “Third World” were likewise coming to prominence. Festivals were screening these works more frequently, and archives had to take note, if only because these nations were rapidly forming their own cinémathèques. Likewise, by the end of the 1970s, programmers had to take notice of the great traditions of Japanese cinema. Although Kurosawa and Mizoguchi were widely known to westerners in the 1950s, awareness of other Japanese directors, notably Ozu, came in the 1970s and 1980s, when the canon was opening up widely.

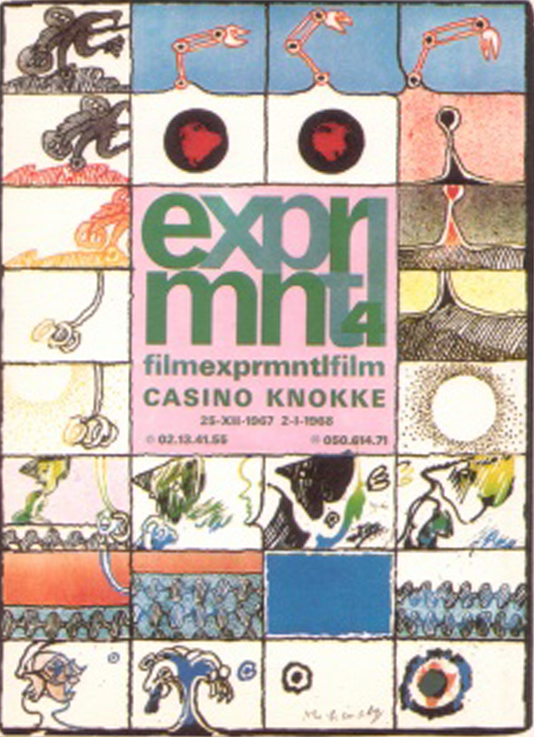

At the same time, avant-garde cinema had taken an oddly “archival” direction. The silent-film canon had included some experimental work, notably abstract films and surrealist and Dada works. Archives had encouraged avant-garde work through festivals, the most famous of which was Belgium’s EXPRMNTL events at Knokke-le-zout from 1958 to 1974. But as collectors and archives began to unearth and restore very early films, such as the Library of Congress Paper Print Collection, adventurous filmmakers began to “remake” them. The most famous effort was Ken Jacobs’ Tom, Tom the Piper’s Son (1969), an optical-printer exercise in which a 1905 Biograph film was slowed, blown up, frozen, and replayed as a series of what Jacobs called “infinitely complex cine-tapestries.”

A lively three-way exchange among filmmakers, archives, and scholars emerged. While so-called Structural films of the 1970s called attention to the peculiar richness of early cinema, many young researchers turned their attention to the period. Books, articles, and dissertations appeared. The trend culminated in a major 1978 conference held in Brighton, England, under the auspices of FIAF. Scholars and archivists met to watch 500 fiction films from 1900-1906, and the fruits of their deliberations were published in two large volumes. Soon came archive-based festivals devoted to silent cinema, in the Italian cities of Pordenone (the Giornate del cinema muto) and Bologna (Cinema ritrovato).

Ivo Blom and Paolo Cherchi Usai at Le Giornate del Cinema Muto, Pordenone; 1997. Photo: DB.

Avant-garde filmmakers eventually lost their taste for early cinema, but researchers and archivists made it a central area of their activity. Early cinema became one of the most mature areas of academic film research. Archivists in turn gave early cinema a privileged place in their work and began to make tinting, toning, and hand-coloring part of proper restoration of silent films. In a reciprocal exchange of energies, as archives made silent films more attractive and intriguing, more scholars were drawn to the area—which drove archivists to press further in their explorations.

More generally, archives began to welcome researchers, and to create facilities for intensive study. While some would screen films only in projection, others allowed suitably trained visitors to watch films at flatbed machines, younger cousins of Mlle. Epstein’s visionneuse. I experienced this change myself: At the Danish Film Archive in 1970, I was shown Dreyer films in their theatre, but when I returned in 1976 I was permitted to study them on a Steenbeck.

David at the former headquarters of the Danish Film Museum, 1976.

Personnel were changing too. If older staff saw the archive’s primary duties as conservation and public exhibition, there arose a generation of younger staff who wanted to encourage scholars to explore their collections. Many of these budding curators had studied film history in universities, so they understood that academic research needed slow, in-depth examination of the films as physical artifacts.

Even older archive hands became more receptive. In 1973, at George Eastman House, James Card permitted me to watch several French films, but only in projection. When I saw La Roue, I realized I had to look more closely. George Pratt allowed me to study certain sequences at a rewind, so there I perched, a reel mounted on either side of me, counting frames in the great train sequence. (Four frames—three frames—two frames!) Langlois, as I’ve mentioned, was surprisingly open to close study as well.

Jacques Ledoux, director of the Brussels Cinémathèque, was somewhat younger than Card and Langlois, and he understood that a new generation of film students would need access to rare classics. In 1979 my wife and collaborator Kristin Thompson was warmly welcomed at the Brussels archive. Three years later I paid my first visit.

Ledoux’s young colleague Gabrielle Claes, who is my age, was very sympathetic to the new research trends. Much of our research since then has relied crucially on this archive’s vast holdings.

At home in Madison, Kristin and I were able to use the extensive collection of Hollywood cinema at the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. As one of the top university-affiliated archives, the WCFTR was designed to foster academic inquiry. Similarly, the staff of the Library of Congress, many of whom had taken degrees in film history, understood that scholars like us were different from the TV producers looking for stock footage or the Robert Mitchum fans who just wanted to watch movies in those pre-video days. The WCFTR and the LoC proved crucial for our work on The Classical Hollywood Cinema (1985), and I continue to draw on the nearly 1930s and 1940s Japanese cinema I studied in the Washington collection.

These three archives proved particularly helpful because they did not confine their collections to official masterpieces. Unlike MoMA, these institutions have been obliged to collect very comprehensively. Required deposits (the LoC), encouraged deposits (Brussels), and complete studio collections (like our Wisconsin Center) permit the bulk viewing necessary to get an extensive sense of what ordinary moviemaking is like.

Other researchers of my generation and later have parallel tales to tell of their encounters with archives in studying Third World film, or documentary, or 1950s widescreen film, or experimental work. I was very lucky to have come of age in a period of unique cooperation between archives and academics.

Technology cracks the canon

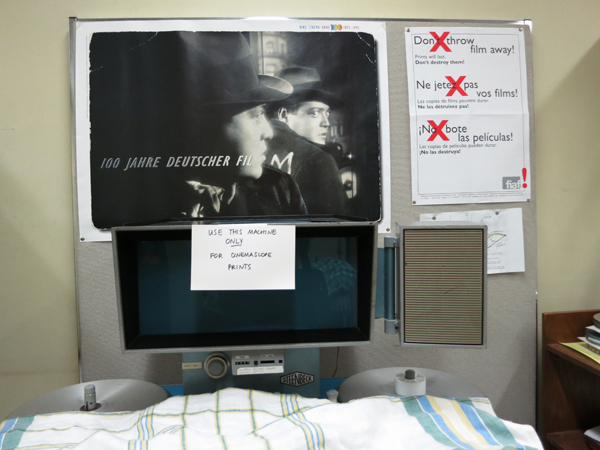

Viewing machine at the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research.

Throughout the 1970s and early 1980s, an economy of scarcity still ruled. Most films, even recent commercial hits, could be found only in studio libraries and public or privately-maintained film archives. Some copies made their way to 16mm, and many teachers and researchers worked with this gauge. But offerings were limited, visual quality was unreliable, and color and widescreen formatting were compromised in 16mm. A procession of new technologies, starting in the 1970s, radically and forever changed access to films.

Cable television permitted audiences to catch up with recent releases, but a few channels ran older titles as well. In the US, American Movie Classics (begun in 1984) was one of the first to identify itself with historical programming; others, most notably Turner Classic Movies (1994) followed. TCM became available in Europe, while the Franco-German channel ARTE broadcast classic films as part of its cultural programming. For researchers of the late 1980s onward, the newly invented videocassette recorder provided a way to capture and study films shown on these specialty cable outlets.

No less important was the emergence of a market in prerecorded videocassettes. When the VHS format triumphed in the early 1980s, consumers had a single standard and began to rent and buy cassettes. Studios, delighted to find a new market for their libraries, released older hits and some classics. Surprisingly large numbers of silent films were transferred to video. A brisk business in piracy arose, with recent hits naturally being the prime target, but some spillover to minor or lesser-known films. In Asia, a great many classics that had been shown on television wound up on bootleg VHS, for sale to the curious and the elderly. In London you could find shops that freely rented and sold copies of classic Bollywood films to the Indian diaspora. During my first visit to Hong Kong, I bought many legal laserdiscs and some, I confess, illegal tapes of obscure items.

Academics around the world began creating personal libraries of films they could not study in any other way. Film departments built vast collections of titles recorded off-air, bought on the legal market, and acquired through more uncertain channels. Before the Internet, professors traveling abroad brought back cassettes for departments of languages and literatures. Reciprocally, the circulation of national classics on videocassette enabled archivists to become aware of new films. Although VHS could never be a preservation format, it allowed for a quick-and-dirty glimpse of a film that might be worth showing or even acquiring. Technology had cracked open the canon.

Archive sweepings.

Purists like me vowed never to show a film to students on a video format. A film released on 35mm, we thought, should be shown in that gauge, or at a pinch in 16mm. This commitment was easy to maintain when anybody saw VHS projected on a large screen: the image looked awful. VHS was best suited for undergraduates analyzing a film at a monitor and for playing extracts in class, to spare wear and tear on a print. Laserdiscs provided better visual quality than tape, but the image still fell far short of film’s. (But its digital sound was undeniably better than the analog 16mm.) The arrival of the DVD at the end of 1997 foreshadowed the coming of digital exhibition and a still further change in how archives and researchers interacted.

The DVD format, one of the most successful entries in the history of consumer electronics, was quickly taken up by the public. The improvements in image and sound were evident to even non-specialists. American studios loved the antipiracy encryption and region coding that promised them control over distribution of the product. (Soon, however, hackers eroded that.) A DVD was versatile, able to be played on computers, videogame consoles, and big-screen home theatres. DVDs had random-access capability, and they respected widescreen formats. Even in early days, a DVD versions of a film tended to be cheaper than a VHS version, so price helped drive out the tape format. And very soon after the launch of DVD, electronics companies offered digital video recorders, which enabled consumers to record broadcast content to a hard drive or to an optical disc.

As with VHS, academic researchers began building libraries of DVDs available at home and abroad. They were also able to record films off-air. In the classroom, DVDs became the format of choice for course screenings, wiping out the 16mm nontheatrical market. The arrival of Blu-ray discs in 2004 confirmed the optical disc as a noncommercial exhibition vehicle. It became difficult for diehards like me to defend showing a worn 16mm print or even a decent 35mm when a BD offered vivid imagery and pinpoint digital sound.

More basically, the DVD signaled the start of “digital convergence,” the idea that any and all moving images could be converted into a common format and sent wherever one wished. The emergence of Internet 2.0 confirmed this development. YouTube (launched in 2005) and other sites created a demand for faster download speeds, which in turn encouraged more video content to be uploaded. From an academic’s viewpoint, the state of play in 2013 is astonishing. Thousands of films, from industrial documentaries to silent comedies and 1940s studio releases, exist online, waiting to be played, downloaded, and sent along to others.

Once more we encounter the interplay between the larger culture, academic research, and archives. With so many films easily available on digital formats, people who relied upon archives have found other options. I’ve been told by archivists that requests to watch items are less common from the general public and certain professional sectors. If you’re writing a biography of Marilyn Monroe, you will need to consult paper documents in archive collections; but you don’t need to request that her films be brought up from the vault. Many academics who have tackled film-related subjects have never watched a film print for research purposes. Home video abolished the economy of scarcity.

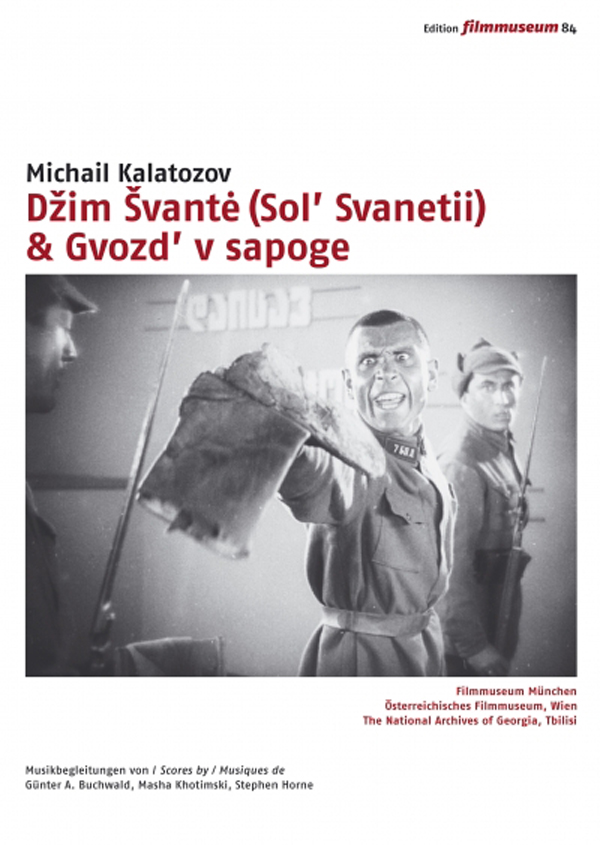

Archives weren’t slow to grasp the importance of the digital revolution. Although the DVD, or even the BD, could not become an archival format, the discs had other possibilities. Now archivists could compare versions of films easily by swapping discs. Moreover, an archive could also release some of its titles for the home and school markets. The Belgian Cinémathèque, the Cineteca di Bologna, and the Danish Film Archive made early and strong initiatives in this direction. A particularly vigorous thrust was made by the Edition Filmmuseum series in 2007 with the launch of its series of rare and well-presented restorations. DVD collections like Treasures from American Film Archives not only offered scarce films but generated financial return that could fund more preservation. In addition, these sets made the activity of preservation and restoration visible to a wide public.

Something similar happened with the Net, as archives began posting clips and even entire films to stir interest in their activities. Perhaps a landmark in this sort of outreach came in 2013, when the New Zealand Film Archive installed for a limited time the entirety of Hitchcock’s previously lost film The White Shadow. The gesture called more attention to the archive’s discovery than a simple publicity announcement could have, and it built good will among silent film aficionados and Hitchcock fans, who would be likely to invest in the DVD eventually.

How much my research was aided by the arrival of home video in various forms can be gauged from the acknowledgments opening my 2006 book, The Way Hollywood Tells It: Story and Style in Modern Movies.

The two archival linchpins of my research, the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Reserch and the Cinémathèque Royale de Belgique, were as usual magnificently cooperative over the ten years during which I gathered material for this book. So thanks to Maxine Fleckner Ducey of Madison, to Gabrielle Claes of Brussels, and to their staffs. I’d also like to thank Ted Turner and Warren Lieberfarb, two far-sighted moguls who have increased our access to the majestic range of American cinema.

In trying to answer questions about changes in narrative and visual style, I did watch many films on 35mm, but I needed to view hundreds of other titles. For bulk acquisition and viewing, nothing beats cable and DVD. So I wanted to thank the man behind Turner Classic Movies, as well as Lieberfarb, the Warner Bros. executive who oversaw the development of the DVD. These men revolutionized the public’s access to classic and contemporary Hollywood films. As a side benefit, their urge to make more money from movies opened up the possibility of our writing better film histories.

Something similar is happening as I write this account. My next book will trace innovations in Hollywood storytelling during the 1940s. With hundreds of films to study, bulk viewing is required. It would take me many years to travel to archives and view these films on film. Some would surely be unavailable anywhere. Fortunately, for the particular questions I’m asking, video often suffices. Not surprisingly, a great many 1940s films, both classics and obscure items, are available on cable television and DVD; indeed, fresh titles keep coming every day. And there is a vast network of collectors who circulate cheap copies of rarities by mail. I have even had to watch obscure items on VOD and YouTube.

Yet archives remain essential for me. For example, the DVD copy of an important film for my project, Guest in the House (1944), had an oddly abrupt opening sequence, not at all the same as that of the script on file in our archive. I was able to watch an original nitrate copy of the film at the Cinematek last summer, and I discovered that the copy commonly circulating was indeed missing a prologue and opening scene. I suspect that the DVD preserves a cut-down version that began showing on American television during the 1950s. During the same stay in Brussels, I was able to see two more films from the period that are not available on DVD or, as far as I know, on any other format.

Such will always be the case, I suspect. With the arrival of Internet 2.0, some futurists predicted the arrival of the “Celestial Jukebox,” a repository of all music ever recorded, merely one click away. I doubt this will come. Even more strongly do I doubt that there will ever be a Celestial Cinémathèque. Too many films of interest to particular researchers will remain unscanned, especially given shrinking archive budgets.

The last technological upheaval was the arrival of the Digital Cinema Initiative. This is the commercial exhibition format that between 2005 and 2012 gradually became the standard. Sponsored by the American studios, the new technology eliminated film prints from theatrical venues. A film arrived at the theatre on a hard drive to be decrypted by a projector that was essentially a computer with a light source inside. By the end of 2013, observers estimated that of the 130,000 screens worldwide, nearly 90 per cent of them were employing some form of digital projection.

Digital restoration at the Cinematek.

Archives weren’t wholly unprepared, as many had started to restore films using digital software. Still, the arrival of digital cinema as an exhibition technology was alarming. For reliable conservation, films would have to be maintained on photochemical supports. But for projection, many titles would have to be converted to Digital Cinema Package files. An archive with tens of thousands of titles faced enormous costs and effort in transferring just a fraction of its collections. Even with DCP conversion becoming faster and more flexible, it would leave thousands of films that could not be shown. Just as bad, with the new format becoming universal, even photochemical prints of indifferent quality became rare artifacts, to be protected rather than circulated. A DCP file can fail without long-term consequences; it can be rebooted or replaced by a clone. A scratched or torn print is damaged forever. It is as if art museums began displaying high-grade digital scans in order to protect their paintings.

When a film original passes into a digital version, be it DVD or Blu-ray or DCP, it loses some features that are significant for those of us who study the history of film artistry. A digital copy loses provenance and patina: the wear and tear of the original copy may be cleaned up by its transposition to digital, and scanning staff will always be tempted to tweak a frame that is judged too dark or too light. Already multitrack sound formats from the 1950s are being redesigned for DVD release because they are too unorthodox for 5.1 home theatre setups.

Sometimes high-intensity scanning of negatives makes a film too sharp, too revealing. Film is inherently forgiving, because the random scatter of photosensitive molecules in the emulsion creates an overall softness and shimmer. A digital scan can become like an X-ray, revealing the edges on Grace Kelly’s makeup or the mascara on John Wayne’s eyelashes. More generally, once a DCP copy is made by one archive, that tends to become the “official” international version, since making others from scratch is costly. In particular, tonal values will become fixed and uniform. A 4K restoration of a classic is likely to be the universal version of the film for quite some time.

Other results are more mixed. I was happy to learn that the DCP format, unlike early DVDs, preserves the frame-by-frame flow of the film original. The sort of frame-counting I performed on La Roue is still possible. But this accurate synchronization holds good only for sound movies. For silents, a fixed running speed is baked into the digital file, so that projectionists lose the capacity to adjust the speed in performance. As with every technology, gains bring losses too.

The canon has largely collapsed. There are no longer “minor” films. Every movie is potentially an object of veneration for some audience, and an answer to some research question. At the same time, the economy of scarcity has become an economy of glut. In my youth, I couldn’t have imagined that film would become so cheap—on Netflix, all you can watch for $7.99 a month.

As movies become ubiquitous, prints become rarities. The distinction between a “viewing print” and a “preservation print” becomes meaningless when there are no longer laboratories to strike new copies. Every print is now precious. And that preciousness is, for me, made material in the flexible, crisp feel of a strip of film between my fingers. Call me antiquarian, but a DVD is just a container. The film is the thing itself.

The archivists who guard these treasures have been a major part of my life. The Brussels Cinematek holds a special place in my heart, and I warmly thank its staff for forty years of helping me to try to understand how cinema works.

This essay was originally published in 75,000 Films, ed. Nicola Mazzanti (Brussels: Yellow Now, 2013). Reprinted with permission.

|

|