Another Shaw Production: Anamorphic Adventures in Hong Kong

David Bordwell

October 2009

What did

teenage viewers think when Kill Bill: Vol. 1 (2003) opened

with the logo for Shawscope? Could they possibly have shared the frisson felt

by baby-boomers who had haunted inner-city theatres thirty years before? Or by

viewers who had watched “Kung-Fu Theatre” on 1980s television? Or

by fanboys like Tarantino, freeze-framing cropped and trembling VHS tapes? For

all those generations, the Shawscope blazon opens onto a world of one-armed swordfighters,

beautiful woman warriors, and kung-fu masters with very long white eyebrows.

Without denying the peculiar pleasures of these sagas, we can peer behind the

logo and study this widescreen format’s place in a broader dynamic. The

Shaw mystique arose out of creative innovations of the studio’s personnel,

guided by the business policies of an all-powerful producer. We can as well analyze

how Shaw directors forged a distinct widescreen aesthetic—one that still,

as Tarantino seems to realize, has much to teach us about the ways movies can

seize spectators. Hong Kong took tutorials in widescreen from its neighbors,

but eventually it could offer lessons, and exhilarating ones, to the world.

Movietown and Its Master

At the end

of World War II, Hong Kong was in a position to grow from a sleepy

port on the South China coast into a capitalist tiger. It enjoyed a deep-water

harbor poised between China and the rest of Asia. A well-educated work force

operated in an atmosphere of dynamic entrepreneurship. Although ruled by a colonial

bureaucracy, citizens were protected by the rule of law and freedom of the press.

Unlike its neighbors, it remained a colonial possession, unshaken by civil war

and unfettered by dictatorship. England ran the government with an unexpected,

possibly unprecedented, lightness of touch, and left the people to make money.

This city

that in 1951 held only two million persons turned into East Asia’s

cinematic miracle, the biggest regional production center outside Japan. Through

the 1950s Hong Kong film companies produced 150 to 200 or more releases

annually. This was because the industry served not only the local market but

theatres in Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, Taiwan, South Korea, and Chinatowns

in Europe and North America. The films were made in several languages,

but two dominated. Mandarin was the principal language of the mainland and of

Taiwan, while Cantonese was spoken in southern China, much of the Chinese diaspora,

and Hong Kong

itself. Thanks to subtitling and dubbing, any film became export-friendly. 1 1

Several Hong Kong-based companies supplied the regional market, but midway through the 1950s,

two transnational entertainment firms got serious about expansion. The older

of the pair was the Shaw Brothers enterprise. The Shaw family, of Shanghai

origins, had been powerful exhibitors and producers in southern China since the

1930s. Wisely stationing their headquarters in Singapore, the several brothers

ruled over an international entertainment empire that included movie houses,

hotels, bowling alleys, amusement parks, and other leisure businesses. Before

the mid-1950s the company was conent to earn money primarily from exhibition

and so turn out a dozen or fewer films per year.

Shaws was

challenged by another Singapore-based firm, the Cathay Organization. Founded

in 1947, it was run by Loke Wan Tho, a Malayan Chinese determined to

modernize the East Asian motion picture business. 2 He

began building comfortable, air-conditioned theatres throughout the region, challenging

the Shaw firm on its own territory. To supply his venues with product, Loke took

over a bankrupt Hong Kong studio facility and renamed it the Motion Picture & General

Investment Co. 2 He

began building comfortable, air-conditioned theatres throughout the region, challenging

the Shaw firm on its own territory. To supply his venues with product, Loke took

over a bankrupt Hong Kong studio facility and renamed it the Motion Picture & General

Investment Co.

The first

MP & GI films were released in 1955, and they quickly seized attention.

In sharp contrast with the costume pictures and Confucian family dramas that

dominated the market, MP & GI’s product embraced American

popular culture. Comedies (Our Sister Hedy, 1957), melodramas

(Her Tender Heart, 1959),

and musicals (Mambo Girl and My Kingdom for a Husband,

both 1957) took place in modern urban settings and celebrated pop music and fresh

young stars. In 1960, MP & GI turned out thirty films, all in Mandarin.

The Shaws

didn’t sit on their hands. The sixth brother, Run Run (Shao Yifu),

came to Hong Kong in 1958 to set the studio on a new path. He began by upgrading

production values. Several studios were producing color films occasionally, but

Run Run made color a main attraction. Shaws’ opulent, song-filled

costume romances Diao Charn (1958) and The Kingdom and

the Beauty (1959) attracted international attention, winning several

prizes at the Asian Film Festival. By 1962 Shaw productions would shift wholly

to color production, a policy that set it apart from other firms. At the same

period Run Run oversaw the construction of a massive production facility,

Movietown, on picturesque Clearwater Bay. Opened in 1961, this film factory—no other

word will do—boasted

1200 employees, six sound stages, and three dubbing studios. Movietown ran around

the clock, with staff working staggered ten-hour shifts. Several hundred employees

were housed in dormitories in the compound. A few years later Shaws added six

more stages and a color processing laboratory. 3 3

As part of

his retooling of production values, Run Run Shaw embraced widescreen cinema.

Although at least one anamorphic film had been made in Hong Kong in the

1950s, 4 no

studio had embraced the format. As another thrust against MP & GI,

Run Run took steps to introduce anamorphic production. Instead of turning

to American sources, he looked to a nearer neighbor. 4 no

studio had embraced the format. As another thrust against MP & GI,

Run Run took steps to introduce anamorphic production. Instead of turning

to American sources, he looked to a nearer neighbor.

The Japanese Connection

Shaws had

already developed some ties to Japan, most steadily in the firm’s reliance

on Tokyo’s Far East Film Laboratory for post-production work. Shaws occasionally

collaborated with Japanese production firms too, notably on coproductions like Princess Yang

Kwei Fei (1955,

with Daiei) and Madame White Snake (1956,

with Toho).

Shaws found its crucial ally in cinematographer Nishimoto Tadashi. After

starting his career in Manchuria during the war, Nishimoto worked at the Shintoho

studio and served as assistant director on Japan’s first anamorphic widescreen

film, The Meiji Emperor and the Great Russo-Japanese War (1957).

He worked for Shaws on Love with an Alien (1958), a coproduction

with Korea, and shot a second picture for the firm, Lady of Mystery (1958).

After returning to Japan to film two anamorphic horror classics for Nakagawa Nobuo

(Black Cat Mansion, 1958, and Ghost of Yotsuya,

1958), he made a long-term commitment to Shaws.

Under his

adopted Chinese name He Lanshan, Nishimoto became a central force at Movietown.

He filmed the big-budget costume pictures of Shaws’ premiere director,

Li Han-hsiang: Yang Kwei Fei (1962); Empress Wu Tse-tien

(1963); and Beyond the Great Wall (1964). Nishimoto shot the

most prestigious production of the period, The Love Eterne (1963),

and he worked on significant films during the decade, including King Hu’s

breakthrough Come Drink with Me (1966) and the melodrama The Blue

and the Black (1966). He also shot more routine musicals, spy thrillers,

and sex films.

Nishimoto convinced Shaws of the value of Japanese craftsmanship. It was

after his arrival that the firm began sending its personnel to Japan to observe

routines at the major studios, and Shaws hired Toho’s special-effects department

to help on The Love Eterne. Most important from our perspective

here, Nishimoto took Shaws into the widescreen era. With Toho’s cooperation,

he brought Tohoscope equipment to Hong Kong, and he instructed cinematographers

in methods of filming in the anamorphic format. 5 Nishimoto

shot the studio’s earliest anamorphic release, Les Belles (1961),

and nearly all of his later films were in the format. 5 Nishimoto

shot the studio’s earliest anamorphic release, Les Belles (1961),

and nearly all of his later films were in the format.

While MP & GI

was slow to adopt color and widescreen, these technical innovations became central

to the newly-outfitted Movietown. But Shaws’ commitment to showcasing these

attractions slowed down production. The firm had released over thirty titles

in 1960, pre-Shawscope, but soon annual output fell to around twenty. A big costume

film might take two years to shoot, especially since Nishimoto was often dividing

his efforts among several projects simultaneously.

In 1964, Loke Wan Tho and other Cathay executives died in a plane

crash, and MP & GI

began to flounder. Given a chance to seize the market, Run Run Shaw

determined to ramp up output. He needed directors who could turn out films quickly.

To supplement the studio’s contract directors, Nishimoto helped Shaws secure

the services of the prolific Japanese director Inoue Umetsugu. Inoue is said

to have signed a contract calling for him to make a hundred films at Shaws. He

didn’t

fulfill his quota, but he did sign seventeen releases from 1967 to 1971. 6 Soon

after Inoue came aboard, Shaws hired five more Japanese directors: Furukawa Takumi,

Nakahira Koh, Shima Koji, Murayama Mitsuo, and Matsuo Akinori. 6 Soon

after Inoue came aboard, Shaws hired five more Japanese directors: Furukawa Takumi,

Nakahira Koh, Shima Koji, Murayama Mitsuo, and Matsuo Akinori. 7 All

were respected as speedy and efficient directors, but they weren’t mere

journeymen. They came from major studios, several had worked under esteemed masters

like Kurosawa, and one, Nakahira Koh, had made a scandalous success with Crazed Fruit (1956),

a portrayal of reckless upper-class youth. Shaws did not trade on the directors’ reputations,

however; all but Inoue worked under Chinese names. 7 All

were respected as speedy and efficient directors, but they weren’t mere

journeymen. They came from major studios, several had worked under esteemed masters

like Kurosawa, and one, Nakahira Koh, had made a scandalous success with Crazed Fruit (1956),

a portrayal of reckless upper-class youth. Shaws did not trade on the directors’ reputations,

however; all but Inoue worked under Chinese names.

From 1967 to 1972, the six émigrés shot over thirty films. They

often brought with them their cinematographers, lighting staff, choreographers,

and performers, so several interpreters had to be on the set. Although some directors

had worked on swordplay films and costume pictures at home, none were entrusted

with such projects at Shaws. Instead, they often simply remade the musicals and

thrillers they had shot in Japan. “The Japanese versions were usually

of higher quality,” producer Chua Lam recalled, “as the aim

of the Hong Kong versions was not to surpass but to copy.” 8 Sometimes

the copying was utterly literal, as in Nakahira Koh’s recycling of

a shot from Crazed Fruit (1956) in the Shaw production Summer Heat (1968). 8 Sometimes

the copying was utterly literal, as in Nakahira Koh’s recycling of

a shot from Crazed Fruit (1956) in the Shaw production Summer Heat (1968).

Despite the tendency toward replication, historians have pointed out that

this “Japanese Whirlwind” brought a new energy to the Shaw product,

pushing the studio toward a more cosmopolitan style, more urban subjects, and

younger stars. I’ll

try to show a little later that the émigrés also provided some

distinctively Japanese approaches to anamorphic filming.

Thanks partly

to the burst of new directing talent, Shaws bumped its output up to forty-two

releases in 1967, and steadied at around thirty per year afterward. By 1970 MP & GI,

renamed Cathay after Loke’s death, was a spent force. Shaws dominated the

market. Every Shaw release announced its dominance with a swaggering prelude.

A blast of trumpets and drums accompanied the studio’s logo (a shield swiped

from another band of brothers, the Warners). Then came the announcement that

the picture was in Shawscope, the name stretched across a double-flared design

reminiscent of U.S. anamorphic advertisements. Here is an early variant, soon

supplanted by the more familiar design centered on the Brothers’ shield.

At the movie’s close, along with the end credit, came the proud phrase, “Another Shaw Production.”

Genres and Styles

Arriving late

to the anamorphic competition, some seven years after the process was introduced

in the U.S., Shaws had a choice of equipment. Like most non-U.S. systems, Shawscope

didn’t rely on the technology developed by Bausch & Lomb

for Twentieth Century-Fox’s CinemaScope. Nor did it adopt Panavision,

which had yet to be available in the region. Charles Wang Cheung Tze, whose

firm supplied equipment to the studios at the time, recalls that Hong Kong

filmmakers used versions of both Dyaliscope and Kowa-based lens systems. 9 9

The French

Dyaliscope system improved the Fox format by offering a variety of anamorphosers

matched to the focal length of each prime lens. This assured a more constant

squeeze across the visual field. 10 Alternatively,

the anamorphosers provided by Japan’s Kowa optics company formed the basis

of several systems, including Tohoscope. Japanese filmmakers placed the Kowa

lenses not in front of the prime lens, as with CinemaScope, but behind it. 10 Alternatively,

the anamorphosers provided by Japan’s Kowa optics company formed the basis

of several systems, including Tohoscope. Japanese filmmakers placed the Kowa

lenses not in front of the prime lens, as with CinemaScope, but behind it. 11 This

arrangement enabled filmmakers to use as a prime lens a 10:1 zoom, which yielded

a great range of focal lengths. 11 This

arrangement enabled filmmakers to use as a prime lens a 10:1 zoom, which yielded

a great range of focal lengths. 12 As

a result Kurosawa and his peers could mount bold wide-angle and telephoto shots

at a time when American filmmakers had difficulty creating such imagery with

CinemaScope. 12 As

a result Kurosawa and his peers could mount bold wide-angle and telephoto shots

at a time when American filmmakers had difficulty creating such imagery with

CinemaScope. 13 13

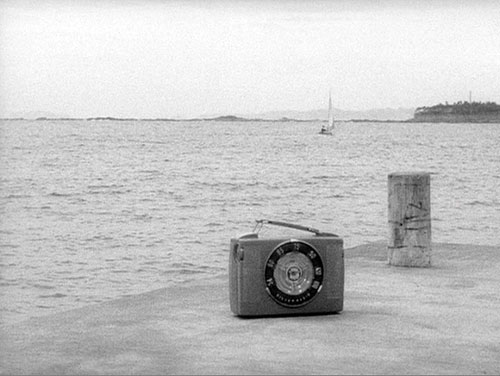

A characteristic

early example of Japanese anamorphic, from Masumura Yasuzo’s Giants

and Toys (1958).

The long lens captures a fight in Kurosawa’s Yojimbo (1961).

According to Nishimoto, Shawscope was based on Tohoscope, although Dyaliscope

lenses were probably also used on Shaw productions. By relying on these anamorphic

processes, Shaw films could exploit variable focal length in the Japanese manner.

Here’s a telephoto frame from the first Shawscope release, Les Belles (1961).

As in other

countries, certain genres became favored vehicles for the anamorphic process.

Going into the 1960s, the studio’s most prestigious genre was the huangmei diao,

the “yellow plum opera.” The films were costume pictures

set in a vague past, with most scenes partially sung. Often focusing on forbidden

love between aristocrats and commoners, the films drew upon traditional theatre,

most notably when male protagonists were played by female stars. The music,

however, was far from traditional, using more modern tonal scales and singing

styles. The cycle was launched by The Heavenly Match (1955),

a film from mainland China that proved a major hit. Shaws followed with the prestigious

pair Diau Charn (1957) and The Kingdom

and the Beauty (1958). The genre elevated many Shaws performers

to stardom, such as Linda Lin Dai, Betty Loh Ti, and Ivy Ling Po.

Most scholars regard The Love Eterne (1963), a Shawscope production,

as the epitome of the cycle, but fairly soon the genre fell out of popularity. 14 14

It took some

time, however, for the huangmei films to appear in the splendor of Shawscope.

Nishimoto Tadashi’s first effort in the genre, The Empress

Wu Tse-tien (1963),

was in production for two years. So the new format was premiered in other genres.

One was the wenyi film, or melodrama. Shaws had rarely indulged in pure

melodrama, but when Doe Ching, an eminent MP & GI director,

was lured away to Shaws, he was allowed to work in that vein. The melancholy Love without End (1961)

illustrates how smoothly the female stars nurtured at Shaws could be integrated

into the wenyi film. Love without End and

other wenyi were

filmed in black and white, but eventually the genre made the transition to color,

with the title sometimes trading on the process (Pink Tears, 1965; The

Rainbow, 1968). Like the huangmei film, the wenyi cycle

wound down in the late 1960s. 15 15

While appealing

to traditional tastes in the opera and wenyi films, Shaws also pursued

the young audience. MP & GI had pointed the way already: My Kingdom

for a Husband (1957) and Calendar Girl (1958) showed

that modern musicals with Westernized pop scores could succeed in the regional

market. 16 Armed

with color and widescreen, Shaw Brothers launched a cycle of cosmopolitan

show-business movies centering on young performers, among them Les Belles, Love Parade (1963), The Dancing Millionairess (1964),

and Till the End of Time (1966). Like the huangmei films,

the musicals wrapped their slim romantic plotlines in grandiose sets, sumptuous

costumes, and melodies that could become hits. It was this genre that Inoue Umetsugu

was imported to invigorate in Hong Kong Nocturne (1967), Hong Kong Rhapsody (1968), The Millionaire Chase (1969),

and many more titles, some adapted from Japanese musicals. 16 Armed

with color and widescreen, Shaw Brothers launched a cycle of cosmopolitan

show-business movies centering on young performers, among them Les Belles, Love Parade (1963), The Dancing Millionairess (1964),

and Till the End of Time (1966). Like the huangmei films,

the musicals wrapped their slim romantic plotlines in grandiose sets, sumptuous

costumes, and melodies that could become hits. It was this genre that Inoue Umetsugu

was imported to invigorate in Hong Kong Nocturne (1967), Hong Kong Rhapsody (1968), The Millionaire Chase (1969),

and many more titles, some adapted from Japanese musicals.

If we consider

what Western countries were doing with widescreen in the mid-1960s, the visual

approach taken in these films can look either naïve or charmingly anachronistic.

For these genres, directors developed a sort of plain-vanilla approach to Scope. 17 Usually

the camera adopts a horizontal and level framing. Figures are arrayed in rows

or scattered in moderate depth, although occasionally a large set permits grand

diagonals. 17 Usually

the camera adopts a horizontal and level framing. Figures are arrayed in rows

or scattered in moderate depth, although occasionally a large set permits grand

diagonals.

Clothesline staging in Love without End (1961).

Eavesdropping in depth (The Bride Napping, 1962).

The Shaw touch: An immense set and diagonal composition for The Love Eterne (1963).

Standard analytical editing, favoring over-the-shoulder shots and moderate

close-ups, is the default method of handling conversation scenes. We sometimes

find aperture framing or a veiling of distant action, especially in the diaphanous

curtains favored in the costume pictures.

Empress Wu Tse-tin (1963): aperture framing and veiled sets.

The cutting rate is moderate to slow; in the films I’ve examined, the

average shot length runs between eight and seventeen seconds. This approach to

Scope threw the emphasis on Movietown’s strengths: costume and set design,

with vibrant colors coordinated across the acreage of the frame.

Technical factors also favored keeping the cinematography simple. Nishimoto

recalled that the Tohoscope lenses couldn’t give very accurate focus. To

judge by the onscreen evidence, focus was particularly difficult at the extremes

of zoom lenses. In the 1960s, filmmakers seem to have favored wide-angle lenses,

even at the cost of bowed verticals. Nishimoto also claims to have typically

shot the color films at an aperture of f5.6 on film with an ASA/ISO rating of

50, both factors which would also minimize depth of field. 18 18

Nevertheless,

compared with the Japanese anamorphic films of the time, especially those in

black and white, the Shaw approach to its in-house genres seems quite conservative.

The huangmei and wenyi films are treated with a pictorial

solemnity that befits their echt-old-country atmosphere and conservative

morality. The primary exception to my generalization about these genres

comes in Inoue’s

musicals, from Hong Kong Nocturne (1967) onward. The musical

numbers and montage sequences tend to be somewhat more dynamic than the ones

we find in the early 1960s. Inoue decorates some passages with canted framings

and off-center compositions.

A canted angle

for a discovery scene in the musical Hong Kong Rhapsody (1968).

Even the straightforward scenes tend to rely more on low angles, more outré visual

effects, and staging in depth, even if not all planes can be well-focused. In

these ways Inoue’s visual style leans a bit toward the prototypical Japanese

use of anamorphic widescreen, which tends to be more varied and flashy than that

elsewhere in Asia, or indeed in Western countries.

A distinctively

Japanese treatment of widescreen, then, was imported to Hong Kong but toned

down. The process is apparent in another genre that emerged in the mid-1960s,

the spy film. The Japanese had already begun imitating the James Bond

series when Hong Kong studios followed suit with The Golden Buddha (1966)

and Angel with the Iron Fists (1967). Two early entries in

the cycle, The Black Falcon (1967) and Interpol 009 (1967)

were made by the imported Japanese directors Furukawa Takumi and Nakahira Koh,

both leaning heavily on their hits back home. Other spy adventures followed,

from MP & GI and other studios as well as from Shaws. As the cycle

faded, Shaws’ émigré directors moved toward the crime thriller,

in such films as Diary of a Lady-Killer (Nakahira, 1969), A Cause

to Kill (Murayama Mitsuo, 1970), and The Lady Professional (Akinori Matsuo, 1971).

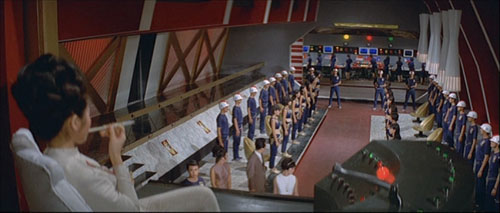

Again, the

mise-en-scène of these genres gets the inflated Movietown treatment, at

once lavish and tacky. The cavernous lairs of Mabuse-like villains are rendered

as vast sets, brilliantly lit and throbbing with saturated primary colors. These

master criminals worry more about interior decoration than world domination.

Angel

with the Iron Fists (1967): A huge Movietown set becomes a master criminal’s

headquarters.

Compared with the other genres I’ve mentioned, though, the spy films

and thrillers tend to have flashier camerawork. They take advantage of Run Run Shaw’s

decision during the building of Movietown to rely on post-dubbing rather than

direct sound. Freed from worrying about microphone placement, the director gains

flexibility of camera position. In the Japanese émigrés’ films,

entire scenes may be handled in low angles, and many shots offer canted framings.

The compositions often make bold use of architecture, slicing the visual

field into modules and spreading the action out to the very edges of the frame.

Partitional framing in The Black Falcon (1967).

Black Falcon: Extreme edge framing for suspense in the anamorphic format.

In particular, the Japanese fondness for partially blocked action, what I’ve

called elsewhere a “game of vision” that teases us with important

story information shifting in and out of visibility, is occasionally seen in

the spy films as well. 19 In

addition, the cutting in these genres tends to be somewhat more rapid than in

the costume pictures and musicals, with average shot lengths in the five- to

seven-second range. 19 In

addition, the cutting in these genres tends to be somewhat more rapid than in

the costume pictures and musicals, with average shot lengths in the five- to

seven-second range.

Three examples

suggest the ingenuity that occasionally emerges from these formula pieces. In Interpol 009 (1967), Nakahira

Koh creates a game of vision when agent 009 is jailed. The other

prisoners are clustered around him in the middle distance, leaving a gap that

reveals his face.

As the men pull a bit away from him, they open up an area in the distance

that a guard can step into, summoning the hero to leave.

Instead of cutting, Nakahira sustains the shot by having the agent leave the

cell, bidding farewell to the others from a tiny slice of space in the distance.

As Japanese directors often do, Nakahira has pulled the action into ever-smaller

zones of depth and obliged us to follow slight changes within quasi-geometrical

patterns.

Murayama’s A Cause to Kill (1970) centers on a woman

who sets up her cheating husband to be murdered, only to find that the husband

has killed the hitman. It is a

frank plagiarism of Dial M for Murder, complete with a cunning

police inspector and byplay with latchkeys. It’s also strongly Japanese

in its stylization, from abstractly composed high angles to aggressive foreground

planes.

A parking lot becomes a geometrical pattern (A Cause to Kill).

A telltale briefcase looms in front of us while characters argue in the distance.

A florid game with a lampshade suggests that Murayama had been watching The Ipcress File (or

maybe Godard’s Contempt).

One of the most striking flourishes comes when the accused man’s lover

is shown sitting down in the bedroom while the cop checks the wife’s handbag

for the latchkey. An off-center shot of the lover sitting down by a chair is

abruptly cut off by a stark close-up in which the handbag occupies the chair’s

spot and the detective lunges forward to seize it.

Achieving this sort of visual accent through tight framing and graphically

matched cutting is common across the history of Japanese cinema and is quite

unlike what we find in most Shaw productions, even other spy films made by Chinese

filmmakers.

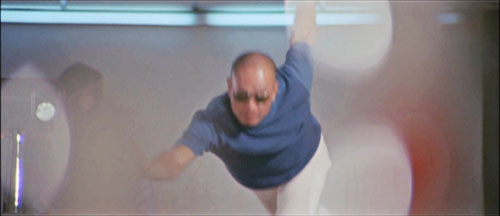

The same sort of stylization emerges in the set-pieces of The Lady Professional (1971).

By now, it’s apparent, directors had the continuously variable focal lengths

afforded by zoom lenses, and director Akinori embraces extremes of rack-focus

and distortion to achieve shock effects. We watch a bowling match from inside

the pin array: The player rolls the ball and we shift focus to a huge close-up

of a pin before it falls over.

A dying man flails at the camera, his hand enlarged out of all measure.

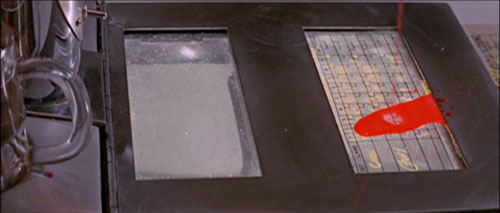

A killing at the bowling alley is rendered in an even more bizarre way. Offscreen

the bowler is shot, and blood drips onto the electronic scoreboard.

We then get a huge close-up of the bloodstain spreading on the scoring panel.

Cut to a shot of the victim slumping as a woman shrieks; the composition makes

the violence hard to detect.

He falls forward dead, into a grotesquely distended close-up.

This last shot seems to have been filmed in the 1.33 format and printed in

anamorphic proportions!

Just as the huangmei and wenyi genres

motivated a solemn approach to cinematography, the suspense and violence of thrillers

justify an exaggerated treatment, along with some startling experimentation.

But I’d argue that the most vigorous innovations occurred in another genre

that, retooled in the mid-1960s, pushed the others out of the spotlight.

Widescreen Action

“Shaws

Launches ‘Action Era,’” read the headline in the October 1965

issue of Southern Screen, the studio’s publicity magazine.

The story explained that the company was developing a new approach to the wuxia pian,

the “film of heroic chivalry.” Films featuring knights

errant and vigorous swordplay had been a mainstay of Chinese cinema since the

silent era. During the 1950s Hong Kong’s Cantonese-language companies

had found a ready audience for their fantasy wuxia pian. Here warriors

both male and female battled monsters, sought hidden treasure, dabbled in black

magic, and displayed astonishing fighting skills, including flying. Cantonese

cinema also developed the kung-fu film, most prominently in the lengthy series

centering on the martial artist Wong Fei-hung. In the kung-fu stories, the

fighters were often shot with rather static and distant coverage. Shaws’ proclamation

set its Mandarin-language product squarely against both the fantasy swordplay

film and the kung-fu films. The Southern Screen publicity

article defined the new trend as a “progressive movement.” “It

breaks with the conventional stagy shooting methods and introduces new techniques

to attain a higher level of realism, particularly in the fighting sequences.” 20 20

Shaws’ initial

offerings in fall of 1965, Hsu Tseng-hung’s Temple of the

Red Lotus and The Twin Swords, did not trigger an

overwhelming response, but the films of early 1966 did. Chang Cheh’s Tiger Boy was

followed quickly by King Hu’s Come Drink with Me,

which became one of the top-grossing Shaw titles of the year. In 1967, Shaws

released eleven wuxia pian,

including Chang Cheh’s huge hit The One-Armed Swordsman.

By 1970, swordplay films were the mainstay of the studio’s output. The rise

of the wuxia film

probably accelerated the decline of the other genres, particularly the huangmei and wenyi pictures.

These had cultivated women stars, but Chang Cheh began pushing for “masculine” genres

that would build up a stable of male actors. Soon the studio would be identified

with a string of stars—Jimmy Wang Yu, David Chiang, Ti Lung,

and Alexander Fu Sheng—all of whom worked with Chang Cheh.

Shaws’ new wuxia pian weren’t utterly original.

Multi-volume martial arts novels had long been a staple of Chinese popular fiction,

and a new wave of writers, led by Jin Yong, had recently begun

publishing earthier, more violent sagas. The new wuxia novels were

inspiring Cantonese and Mandarin filmmakers to rethink swordplay cinema when

Shaws launched its Action Era. 21 Perhaps

the most noteworthy competitor to the Shaws initiative was The Jade Bow (1965),

from the Great Wall studio. In addition, imported Japanese swordplay films

exercised a powerful influence over all companies. Shaws distributed swordplay

films from the Toei studio and the Zatoichi series from Daiei, and Run Run Shaw

screened these imports for his staff to study. The marketing muscle of Shaw Brothers

assured that its wuxia cycle

played the prime role in renewing the local martial arts film tradition. 21 Perhaps

the most noteworthy competitor to the Shaws initiative was The Jade Bow (1965),

from the Great Wall studio. In addition, imported Japanese swordplay films

exercised a powerful influence over all companies. Shaws distributed swordplay

films from the Toei studio and the Zatoichi series from Daiei, and Run Run Shaw

screened these imports for his staff to study. The marketing muscle of Shaw Brothers

assured that its wuxia cycle

played the prime role in renewing the local martial arts film tradition.

As we would

expect, the most dynamic stylistic innovations arose in response to the genre’s

demand for vigorous action sequences. At one level, Shawscope encouraged directors

to dwell on intra-shot effects, staging the principal moves within a single take.

Often the influence of Japanese cinema is apparent.

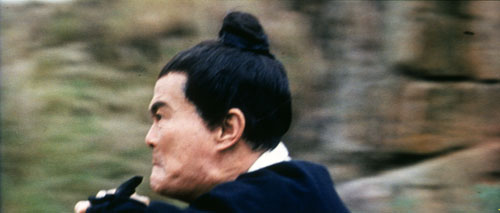

Consider what

we might call the one-by-one tracking shot. This follows a fighter encountering

and eliminating a string of opponents, each of whom plunges into and falls out

of the frame at the right moment. This tightly choreographed camera movement

is rare in Cantonese martial arts films of the 1950s but is common in Japanese

swordplay films. Used extensively in Come Drink with Me and

other Shaw films, the one-by-one tracking shot seems a clear effort to make the

action scenes less stagy. 22 Similarly,

the low-angle shots that we find in the Shaw films of the Japanese émigrés

seem to have inspired the wuxia directors. Chang Cheh found such

framings “warm” (as

opposed to “cold” high angles) and he recalled that “passionate,

spirited ‘new school’ directors used a lot of (extremely) low-angle

shots. Directors of my generation were often mocked for ‘having the cinematographer

crawl on the ground all the time.’” 22 Similarly,

the low-angle shots that we find in the Shaw films of the Japanese émigrés

seem to have inspired the wuxia directors. Chang Cheh found such

framings “warm” (as

opposed to “cold” high angles) and he recalled that “passionate,

spirited ‘new school’ directors used a lot of (extremely) low-angle

shots. Directors of my generation were often mocked for ‘having the cinematographer

crawl on the ground all the time.’” 23 Chang

experimented with shooting most scenes of The Assassin (1967) in

static low-angle framings, some quite boldly composed. 23 Chang

experimented with shooting most scenes of The Assassin (1967) in

static low-angle framings, some quite boldly composed. 24 24

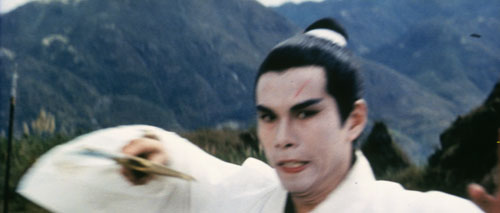

Other stylistic

strategies of Japanese swordplay films were smoothly assimilated to Shawscope.

Swordsmen who have been dealt a lethal cut stand for a time before eventually

collapsing. Fighters are configured in various degrees of depth, as in this shot

from The One-Armed Swordsman (1967).

Warriors swap places in the course of a shot, or leap in from offscreen, or

turn to reveal wounds as they fall out of the foreground. Likewise, Shaw directors

borrowed the Japanese device of blocked views. Sometimes figures will flash through

the foreground, quite close to the camera, creating a flickering view of the

action. In Chor Yuen’s Intimate Confessions of a Chinese Courtesan (1972),

the attack on a figure in a cart…

…is interrupted by figures flitting through the foreground…

…giving an extra weight to the blow we finally see.

Yet the influence of Japanese cinema wasn’t all-encompassing. The local

directors seemed to have avoided many of the most obvious features of Japanese

technique, such as the densely composed frames and free panning shots of Kurosawa’s Yojimbo (1961)

and Sanjuro (1962). Many of the swordplay films make use of the gigantic

sets and colorful costume design that were associated with the Shawscope product,

as in the climactic fight in The Assassin.

As we’ve seen, the émigré directors, even though they

had worked on period swordplay films in Japan, were not assigned wuxia projects,

so local directors had an opportunity to create something distinctive.

There are as well important differences in the national martial-arts traditions.

Japanese sword art (kenjutsu) emphasizes the power of the single stroke.

There is an entire division of technique (iaido, or iai-jutsu)

devoted solely to drawing the sword and cutting the adversary in one movement.

Prolonged sparring with each opponent is less significant that finding the precise

moment to thrust or slash. As a result, Japanese swordplay films tend to emphasize

the long buildup to the decisive stroke. This idea forms the basis of the famous

final scene of Sanjuro, a suspenseful, nearly unmoving face-off that

is resolved in an instant.

A similar emphasis on the sudden stroke can sometimes be found in Shaw films

of the late 1960s, but most often the heavier swords, spears, and other weapons

of the Chinese martial arts traditions favor extended fights. These scenes are

filled with thrusts, parries, feints, and evasive maneuvers. In Have Sword

Will Travel (1969), the final fight runs for over twenty minutes. The convention

of prolonged combat carries over to the kung-fu film, in which two fighters may

battle at exhausting length. To cover such extended action in single shots would

require long and intricate takes, so Hong Kong martial arts films gravitated

toward cutting. The complicated leaps, twists, and stratagems are much easier

to present in several shots. Just as important, the sustained combat creates

its own rhythm, which can be amplified or quickened by the editing pace.

So orchestrating

shot-to-shot relations became central to the wuxia pian. Many of

the 1960s swordplay films are cut reasonably fast, with average shot lengths

in the 5- to 6-second range, and some are swiftly paced, such as The Temple

of the Red Lotus (3.6 seconds ASL). As in other genres, the default

is analytical editing, with master shots broken into closer views. It seems,

though, that Shaws encouraged directors to use quite close views of individual

fighters, some lunging to the camera, others reacting abruptly to a blow. Typical

of this tendency is what we might call the fatal insert, in which a very brief

close-up of the blade inflicting the wound interrupts full shots of the fighters.

Breaking down a fight into details this way was at variance with the distant

coverage of fights in the Wong Fei-hung films.

Along with

analytical editing Shaw directors relied on constructive editing. Here no master

shot supplies a full view of the action; the viewer must build up a sense what’s

happening from bits of adjacent spaces. This is of course common in many traditions,

including the Hollywood western. (Shot A shows hero firing/shot B shows bushwhacker

being hit.) But constructive editing is particularly important in Hong Kong

cinema because it solves a problem that Japanese directors didn’t face.

Chinese traditions

of martial arts include certain techniques which are rather difficult to represent

on film. Even outside the fantasy swordplay tales, fighters execute quasi-supernatural

feats of strength or grace. The obvious instance is the “weightless

leap.” Heroes

vault into the air, sometimes sustaining themselves aloft for quite a while.

How can the film represent this? It’s hard to convey in a single shot,

though early Chinese directors used crude superimpositions to suggest it. Today’s

equivalent is the sort of CGI imagery we find in Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000), Hero (2002),

and their successors. In pre-digital days, the flying swordsman could be lifted

on thin wires, another technique that filmmakers seem to have borrowed from Japan. 25 More

commonly, weightless leaps were created out of constructive editing. A fighter

is shown springing up in the first shot, flying in the second, and landing in

the third. By breaking the event into chunks, the weightless leap could be made

clear, and although audiences probably sensed the artifice involved, if the cutting

were fast enough, the sequence could pass muster. 25 More

commonly, weightless leaps were created out of constructive editing. A fighter

is shown springing up in the first shot, flying in the second, and landing in

the third. By breaking the event into chunks, the weightless leap could be made

clear, and although audiences probably sensed the artifice involved, if the cutting

were fast enough, the sequence could pass muster.

In these ways,

Shaw directors adapted analytical and constructive editing to the demands of

swordplay films. But the wuxia directors enhanced the conventions that

they received. Elsewhere I’ve argued that the martial-arts film was Hong Kong’s

greatest collective contribution to the aesthetics of film, as historically important

as Soviet Montage, German Expressionism, and other stylistic schools. 26 Without

any knowledge of European avant-garde movements, the Hong Kong directors

intuitively discovered fresh and forceful approaches to rendering movement. They

merged indigenous practices of theatre and martial arts with principles of international “film

language” to create an expressive, visceral cinema. You don’t have

to be Quentin Tarantino to recognize that the Shaw studio created a tradition

of uniquely arousing filmmaking. 26 Without

any knowledge of European avant-garde movements, the Hong Kong directors

intuitively discovered fresh and forceful approaches to rendering movement. They

merged indigenous practices of theatre and martial arts with principles of international “film

language” to create an expressive, visceral cinema. You don’t have

to be Quentin Tarantino to recognize that the Shaw studio created a tradition

of uniquely arousing filmmaking.

What sorts of innovations do we find? For one thing, more than their peers

in other Movietown genres the wuxia directors used editing to create

dynamic graphic patterns. In the huangmei and musical films the rich

costumes tend to be part of a static array, dotted across the wide format. The martial-arts

films put the colors into motion, flashing costumes past us in bold patterns.

Thus in one scene of Golden Swallow, each fighter challenging Silver Roc

wears a different shade, and the combat that results presents a swirl of color,

with his white outfit clashing with the orange, brown, black, gray, and red costumes

of his adversaries.

The visceral impact of color is nowhere more apparent than in the use

of blood. It becomes vibrant red dabs, blots, and smears on any costume, and

can tint any scene. In The One-Armed Swordsman, when our hero

contemplates a knife, it picks up the reflection of a red fabric nearby and glints

as a bloody blade. More outrageously, the blood can fill the Shawscope screen.

One of the most remarkable films of the cycle, Cheng Kang’s 14 Amazons (1972),

delivers a stunning climax. The widows have tracked down the men who have

killed their husbands, and one woman warrior is battling the principal villain.

She slashes frantically at him and a jet of blood bursts across the frame.

Outrageously stylized, even cartoonish, the shot has the impact of a blow

to the spectator’s eye.

Sometimes the rapid cutting takes on bold rhythmic patterns. The best

example I’ve found comes in King Hu’s application of what Eisenstein

calls metric editing. A battle scene in Come Drink with Me is

designed and cut according to an arithmetical principle. In medium-shot, Golden Swallow

starts to run to the right (30 frames).

In another medium shot one opponent runs toward her (10 frames).

Another opponent runs toward her (10 frames).

Another medium shot: A third opponent runs to the camera, also in 10 frames.

In a climactic medium-shot, all three clash in a 12-frame shot.

It’s as if the initial thirty-frame shot has been splintered into three

equal follow-ups, the whole capped by a slightly more sustained shot. The effect

is to arrest our attention and create a series of percussive accents that initiate

the more sustained combat.

Some of King Hu’s wilder experiments were launched after he left

Shaws to make films in Taiwan, 27 but

other scenes in Come Drink with Me reveal one of his most original

extensions of editing principles. How, he asks in effect, can one show the strength

of warriors without either using special effects in the full shot or resorting

to the roundabout artifice of constructive editing? His answer is to modify analytical cutting

in ways that grant power and authority to his heroes. 27 but

other scenes in Come Drink with Me reveal one of his most original

extensions of editing principles. How, he asks in effect, can one show the strength

of warriors without either using special effects in the full shot or resorting

to the roundabout artifice of constructive editing? His answer is to modify analytical cutting

in ways that grant power and authority to his heroes.

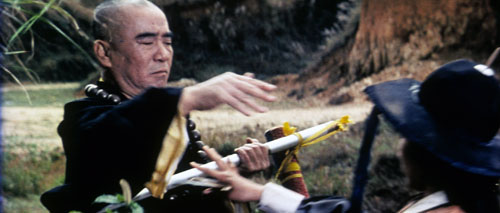

Take the premise that fighters can concentrate their chi and expel

it, in pressurized form, into a single blow from the palm. How to present this?

Outside a temple, Golden Swallow smacks an opponent open-handed, and in

the next shot the man is already reeling away several feet from her.

She meets her match in the abbot, who applies the same technique to her.

Drawing on the master-shot/closer view schema, King Hu creates jolting ellipses

that must be read as powerful blows. The smack takes place in the cut itself,

and the Shawscope format amplifies its force by extending the distance across

which the figure can be flung.

Probably the most notorious stylistic device of Hong Kong swordplay

films is the crashing zoom. In his script for Kill Bill, Tarantino

wrote: “We

do a Shaw Brothers-style quick zoom into a cu of her face.” 28 Perhaps

because of the uncertain focus available with the Kowa lenses, zoom shots are

fairly rare at the start of the wuxia cycle. When they do crop up, they’re

more common in moments of confrontation or dialogue than in fight scenes. In Golden Swallow,

when Silver Roc and Golden Whip face off in an inn, there is an abrupt zoom

past the men to show the heroine arriving in the distance. 28 Perhaps

because of the uncertain focus available with the Kowa lenses, zoom shots are

fairly rare at the start of the wuxia cycle. When they do crop up, they’re

more common in moments of confrontation or dialogue than in fight scenes. In Golden Swallow,

when Silver Roc and Golden Whip face off in an inn, there is an abrupt zoom

past the men to show the heroine arriving in the distance.

By 1968, though, filmmakers were integrating zoom shots into combat scenes

in ways that enhance editing choices. The aim, it seems, is less to zoom

in the middle of a shot than to use the zoom to underscore the shot’s beginning

or end. A fight in Yen Chun’s That Fiery Girl (1968)

employs several of the tactics I’ve already mentioned—the low angle,

the fighters who break our view by flitting through the foreground—but

it is launched by a framing that starts on an adversary and zooms back as he

hurls himself on the hero.

Directors went on to refine the device, exploiting the zoom’s power

to accentuate pauses in the action and to blend with the match-on-action cut.

In the 1970s, Shaw directors would commonly end a shot with a zoom in to an object

or a gesture, then cut to a new angle on the action, sometimes zooming out from

the same item. The effect is again to fit the smash zoom to the fight’s

pattern of blows and pauses, but at a finer-grained level. In Blood Brothers (1973)

Chang Cheh begins and ends his shot with symmetrical zooms centering on

a sword.

In all,

Shaw Brothers’ wuxia directors imaginatively transformed the conventions

that they inherited from Japanese and western cinema. Less statuesque than the huangmei films,

less inclined to one-off flourishes than the musicals and thrillers, the swordplay

films fused movement, color, cutting, and the plastic zoom into a rousing widescreen

style. The result was a rich legacy, developed both in the Hong Kong studio and

elsewhere.

Chang Cheh

continued to experiment, never losing sight of how Shawscope could extend the

visceral power of combat. By the mid-1970s he was employing fast cutting, tight

close-ups of faces and hands, and virtuoso shots that combined panning, tracking,

zooming, and rack focus. Likewise, Lau Kar-leung, one of Chang’s principal

choreographers, started directing in 1975, and he developed the Shaw innovations.

Drawing on martial-arts traditions throughout East Asia, Lau mounted fight

sequences of unprecedented intricacy, using the resources of thrusting movement,

turbulent color, pulsating cutting, and the precision zoom. He makes every bit

of the widescreen format a potential arena of combat. In Return to the

36th Chamber of Shaolin (1980),

the hero rushes toward an adversary and his movement is captured in an abrupt

zoom back.

He lifts his opponent’s arm and punches his chest, creating a focal

point on the far left of the anamorphic frame.

As he struggles, another fighter pops into the space cleared by the two figures’ action.

And soon that second opponent slips out from the first one’s armpit

and takes on our hero.

This sense of “all-over” shot design is seen in less frantic moments

as well. When Lau’s fights pause, his compositions snick securely into

place on the wide screen. Below are paused moments from Heroes of the East (1979;

aka Shaolin Challenges Ninja) and Legendary Weapons of China (1982).

While Spielberg, Lucas, De Palma, Carpenter, Hill, and other young American

directors were rediscovering the kinetic arousal of silent-cinema technique,

the Shaw filmmakers were doing much the same, and more inventively.

Outside the studio, the Shaw heritage was developed by King Hu in his

Taiwanese productions and by the younger Hong Kong directors (Sammo Hung,

Yuen Woo Ping) who emerged in the 1970s. Competing firms not only imitated

Shaws but also pushed beyond them, as for instance in Chia Chuang’s

remarkable Redress (1969), for the Wing Kun studio. Cathay, Shaws’ old

rival, was on its last legs when it drafted Wang Xinglei, a Taiwanese director,

to make a big-budget wuxia entry, Escort over Tiger Hills (1969).

It betrays the strong influence of Shaw directors, especially King Hu, but

it also moves in several new directions. Wang tries a little of everything—slow

motion, zooms, superimpositions, color tints, single-frame shots, and jump cuts.

The freedom of camera angle in the fights is even greater than in the Movietown

product.

At the climax, an astonishing montage stretches a warrior’s fall across

five shots in a manner that recalls the Eisenstein of Strike and Battleship Potemkin. 29 29

Scenes such as this offer decisive evidence that the Asian martial arts

film of the 1960s and 1970s provided a more venturesome, exhilarating use of

the anamorphic format than we can find in virtually any other national cinema

of the period.

Run Run Shaw, his Japanese creative personnel, and the directors

who launched the Action Era all laid the foundations of the modern Chinese

martial arts film. Shawscope helped the studio upgrade and refine its genres,

surpass the competition, and establish the company as the premiere Asian source

of filmed entertainment. Yet as often happens in fast-changing Hong Kong,

Shaws’ reign was short-lived. In 1970, Raymond Chow, Run Run’s

chief lieutenant, broke away and with his assistant Leonard Ho founded the

Golden Harvest company. Thanks to the success of Bruce Lee’s Big Boss (1971)

and the followup films, Chow’s studio quickly captured box-office supremacy.

Through the 1970s and the early 1980s, Lee, Michael Hui, Sammo Hung,

Jackie Chan, and other stars personified Golden Harvest’s formula

of kung-fu action and satiric comedy. Even Nishimoto switched to the winning

team, leaving Shaws to shoot Lee’s The Way of the Dragon (1972)

and Hui’s Games Gamblers Play (1974). 30 30

Over these

years Shaws’ swordplay and kung-fu continued to dominate the studio’s

output, while the rest devolved into bumptious comedies and sensational erotica.

Run Run Shaw invested in several western productions, notably Taipan (1974), Meteor (1978),

and Blade Runner (1982). Losing market share to Golden Harvest and

other rivals, the studio curtailed film production in 1985. Movietown became

chiefly devoted to shooting television series for Run Run’s local

channel, TVB. 31 31

By then, anamorphic widescreen production had begun to tail off across the

territory, not to be revived until the 1990s. Nevertheless, Shawscope had introduced

other countries of East Asia to the format, and producers in Taiwan and

Korea sought to give their films that extra production value associated with

the Shawscope logo. 32 (Young

filmmakers across the region, such as those in the New Taiwanese Cinema,

would later reject the wide format as a gesture of rebellion against popular

cinema.) At a more fundamental level, Movietown’s contribution to the art

of widescreen cinema was registered in the look and feel of all the action pictures

that crowded world screens in the boom years of the 1980s and 1990s. John Woo,

assistant director to Chang Cheh, never concealed his debt to his mentor.

Well before Kill Bill,

Tsui Hark had crafted homages to Shaw Brothers’ golden age in Once upon

a Time in China (1991) and The Blade (1995). Shawscope

helped Hong Kong filmmakers forge, if not a wholly new film language, a

robust and exuberant dialect. 32 (Young

filmmakers across the region, such as those in the New Taiwanese Cinema,

would later reject the wide format as a gesture of rebellion against popular

cinema.) At a more fundamental level, Movietown’s contribution to the art

of widescreen cinema was registered in the look and feel of all the action pictures

that crowded world screens in the boom years of the 1980s and 1990s. John Woo,

assistant director to Chang Cheh, never concealed his debt to his mentor.

Well before Kill Bill,

Tsui Hark had crafted homages to Shaw Brothers’ golden age in Once upon

a Time in China (1991) and The Blade (1995). Shawscope

helped Hong Kong filmmakers forge, if not a wholly new film language, a

robust and exuberant dialect.

Notes

For assistance on this essay, I am grateful to Darrell Davis, Emilie Yeh Yueh-yu,

Stephanie Ng, Sam Ho, Casey Lee, Stephen Teo, and the late

Charles Wang Cheung Tze, of Salon Films, Hong Kong.

1 :

The most comprehensive

study of Hong Kong film history of this period remains Stephen Teo, Hong Kong Cinema:

The Extra Dimensions (London: British Film Institute, 1997).

2 :

Poshek Fu, “Hong Kong and Singapore: A History of the Cathay Cinema,” in The Cathay Story,

ed. Wong Ain-ling (Hong Kong: Hong Kong Film Archive, 2002), 66–70.

3 :

For a survey of Shaw Brothers’ development during the period, see

Poshek Fu, “Going Global: A Cultural History of the Shaw Brothers

Studio, 1960–1970,” in Border

Crossings in Hong Kong Cinema, ed. Law Kar (Hong Kong:

Leisure and Cultural Services Department/ Hong Kong International Film Festival,

2000), 43–51.

4 :

The film was Mulan,

the Girl Who Went to War (Guojia company, 1957). See Hong Kong

Filmography vol.

IV: 1953-1959 (Hong Kong: Hong Kong Film Archive, 2003), 226.

5 :

See Han Yanli, “Japanese

Cinematographer Nishimoto Tadashi’s Hong Kong Romance,” Hong Kong

Film Archive Newsletter no. 32 (May 2005), 13-14. Nishimoto’s

recollections are presented in a book-length interview in Japanese: Nishimoto

Tadashi, Yamada Koichi, and Yamane Sadao, Honken e no michi: Nakagawa Nobuo

kara Burusu Rie [The Road to Hong Kong: From Nakagawa Nobuo

to Bruce Lee] (Tokyo: Chikumashobo, 204). He discusses the development of

Shawscope on pp. 114–120.

6 :

For a detailed account of Inoue’s years at Shaw Brothers, see Darrell

Davis and Emilie Yeh Yueh-yu, “Inoue at Shaws: The Wellspring of Youth,” in The

Shaw Screen: A Preliminary Study, ed. Wong Ain-ling (Hong Kong: Hong Kong

Film Archive, 2003), 255–271, as well as the biographical entry in same

volume, 318–319.

7 :

See Kinnia Yau Shuk-ting, “Hong Kong and Japan: Not One Less, “ in

Law, Border

Crossings, 106–109; Kinnia Yau, “Interview with Umetsugu Inoue,” in

Law, Border Crossings, 144–147. See as well the biographical entries

in Wong, The Shaw Screen, 318–319, 325–328, 336–337.

8 :

Quoted in Law Kar, Kinnia Yau Shuk-ting, and June Lam Pui-wah, “Transnational

Collaborations and Activities of Shaw Brothers and Golden Harvest: An Interview

with Chua Lam,” in

Law, Border Crossings, 139.

9 :

Interview with Charles Wang Cheung Tze, Hong Kong, November 2003, and email

correspondence October 2006.

10 :

On Dyaliscope, see Olivier Rousseau, “Les procédés

anamorphiques français

concurrent du CinemaScope (1953–1971),” in Le CinemaScope entre

art et industrie, ed. Jean-Jacques Meusy (Paris: Association française

de recherches sur l’histoire du cinéma, 2003), 111–112. See

also Alain Monclin, Optique et prises de vues (Paris: FEMIS, 1994), 255.

11 :

Interviews with Roy Wagner, ASC, Los Angeles, June 2005.

12 : “Put

behind an off-the-shelf 10:1 zoom lens, they didn’t look too bad—it

was probably the failings of the zoom lens that hid the shortcomings of the rear

anamorphoser” (David Samuelson, “Golden Years,” American Cinematographer 84, 9

[September 2003], 76).

13 :

Charles Wang Cheung Tze indicates that several Hong Kong filmmakers still

used Kowa lenses after his firm, Salon Films, made anamorphic Panavision available.

(Interview, November 2003.) Ramachandra Babu, a Malayam cinematographer,

claims that Indian cinema continues to use Kowa anamorposers “in large

numbers” (The History and Practice of Cinematography in India,

29 January 2004, p. 29,

at www.sarai.net/cinematography/pdf/interviews).

14 :

Edwin W. Chen, “Musical

China, Classical Impressions: A Preliminary Study of Shaws’ Huangmei

Diao Film,” in Wong, The Shaw Screen, 53–56.

15 :

Wong Ain-ling, “Colour

in Simplicity: On the Wenyi Films of Shaws,” in Wong, The Shaw Screen, 192, 204.

16 :

Yung Sai-shing, “From The

Love Parade to My Kingdom for a Husband: Hollywood Musicals and

Cantonese Opera Films of the 1950s,” in Wong, The Cathay Story,

193–198; see also Michael Lam, “Strangers in Paradise,” in

Wong, The Cathay Story, 200–212.

17 :

For a comparison with visual style in early U.S. CinemaScope, see my essay, “CinemaScope:

The Modern Miracle You See without Glasses,” in Poetics of Cinema (New

York: Routledge, 2008), 281–325.

18 :

Silas Lee, “Interview

with He Lanshan,” in A Study of Hong Kong Cinema in the 1970s,

ed. Li Cheuk-to (Hong Kong: Urban Council/ Hong Kong International

Film Festival, 1984), 121–122.

19 :

David Bordwell, Figures

Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging (Berkeley: University of California

Press, 2005), 83–139.

20 :

Law Kar, “The Origin and Development of Shaws’ Colour Century,” in

Wong, The Shaw Screen, 129.

21 :

Law, “Origin

and Development,” 130–132.

22 :

See my “Richness

through Imperfection: King Hu and the Glimpse,” inThe Cinema of

HongKong: History, Arts, Identity, ed. David Desser and Poshek Fu

(Cambridge University Press, 2000), pp. 113–136.

23 :

Chang Cheh, A

Memoir, ed. Wong Ain-ling, Kwok Ching-ling, and May Ng (Hong Kong:

Hong Kong Film Archive, 2004), 82.

24 :

Chang, A Memoir, 86.

25 :

According to Lau Kar-leung, he and Tong Kai saw wirework in the Japanese film The Bloody Shuriken (Akai shuriken,

1965) and decided to use it on The Jade Bow. “Interview

with Lau Kar-leung: We Always Had Kung Fu,” in A

Tribute to Action Choreographers, ed. Li Cheuk-to (Hong Kong:

Hong Kong

International Film Festival, 2006), 61.

26 :

See my “Aesthetics

in Action: Kung Fu, Gunplay, and Cinematic Expressivity,” in At Full Speed:

Hong Kong Cinema in a Borderless World, ed. Esther C. M. Yau

(Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2001), pp. 73–93. I make the

case at greater length in Planet Hong Kong: Popular Cinema and

the Art of Entertainment (Cambridge:

Harvard University Press, 2000), 199–260.

27 :

See Bordwell, “Richness

through Imperfection,” 113–136; Planet Hong Kong, 254–260.

28 :

See the Kill

Bill screenplay available at <www.fexon.com/screenplay.php?action=download&scid=14>,

p. 24 of pdf file.

29 :

For background on Escort over Tiger Hills see Stephen Teo, “Cathay

and the Wuxia Movie,” in Wong, The Cathay Story, 108–121.

30 :

His last film, however, was for Shaws: Super Inframan (1975).

31 : In the 1980s

and 1990s Shaws continued to release occasional quasi-independent productions,

often under the Cosmopolitan brand.

32 :

Elsewhere on this site I discuss Hou Hsiao-hsien’s use of the wide

format in his popular films of the early 1980s: www.davidbordwell.net/books/figures_intro.php?ss=4.

|

|