Rex Stout: Logomachizing

June 2020

Once I lived in humble hovels

And wrote a few legitimate novels.

Now, tiring of the pangs of hunger,

I ply the trade of mystery monger.

Murder, mayhem, gun and knife,

Violent death, my staff of life!

I wrote, through eating not bewhiles,

Of fate profound and secret trials.

Now—calmed the empty belly’s fury.

I write of guilt and trial by jury.

Suspense, excitement, thrills, suspicion,

Sources of excellent nutrition!

I took men’s souls on bitter cruises,

Explored the heart and necked the Muses.

But now to me I say: poor critter,

Be fed, and let who will be bitter.

Clues, deductions right and wrong,

O Mystery! Of thee I mong!

Rex Stout, “Apologia Pro Vita Sua”

Today Rex Stout isn’t as well-known as he once was. Do young folks read his books, or watch the TV shows based on them? For me, in the early 1960s the adventures of Nero Wolfe and Archie Goodwin provided one model of grownup behavior—part of the vista revealed by the Adolescent Window.

For decades since then, I’ve returned to Stout’s books at intervals; as the fans say, they’re exceptionally rereadable. Now, while working on a book on popular narrative in fiction and film, with an emphasis on crime and mystery storytelling, I thought it was time to dig in more analytically.

The result has turned out to be far longer than it can be as a chapter in the book. So I post it here as a kind of homage—but also as an argument for the artistic accomplishment of a writer who has given me a lifetime of pleasure.

Stout had an exceptionally long career. He was born in 1886 in Noblesville, Indiana, to a politically liberal Quaker family. Rex was a child prodigy, a whiz at spelling and mathematics. He decided college had nothing to offer him, and after bouncing around (usher, bookkeeper, Navy yeoman, etc.) he settled in New York City to try to write. Between 1912 and 1917 he published over thirty stories and four novels, mostly in pulp magazines. At age twenty-seven he gave up writing to run a company that arranged for school children to set up savings accounts. The earnings from this business enabled him to move to Europe and launch a second writing career.

That career began in the auspicious year of 1929. His first novel, How Like a God, appeared in the same fall season as Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury, Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms, and Thomas Wolfe’s Look Homeward, Angel. It was also a splendid year for crime: Hammett’s Red Harvest and The Dain Curse were published in book form, along with Ellery Queen’s Roman Hat Mystery, S. S. Van Dine’s Scarab Murder Case, Anthony Berkeley’s Poisoned Chocolates Case, and W. R. Burnett’s Little Caesar. The connection isn’t just a matter of timing. Stout’s novel, for all its literary ambition, is based on a suspense situation: the central action consists of a man climbing a staircase to commit a murder, while his story is told in flashbacks.

How Like a God put Stout among authors who were adapting experimental techniques for a wider readership—a sort of moderate or middlebrow modernism. How Like a God was called “an extraordinarily brilliant and fascinating piece of work.” 1 His next novel, Seed on the Wind (1930) was also formally daring, telling its story in reverse order. It made “the Lawrence excursion into sexual psychology seem pale and artificial.” 1 His next novel, Seed on the Wind (1930) was also formally daring, telling its story in reverse order. It made “the Lawrence excursion into sexual psychology seem pale and artificial.” 2 Stout was compared favorably with Dostoevsky and Aldous Huxley. 2 Stout was compared favorably with Dostoevsky and Aldous Huxley. 3 In a contemporary essay surveying the modern novel, a distinguished academic had no hesitation including Stout in the company of Woolf, Dos Passos, and Faulkner. 3 In a contemporary essay surveying the modern novel, a distinguished academic had no hesitation including Stout in the company of Woolf, Dos Passos, and Faulkner. 4 4

Accordingly, Stout mingled with the literati. He met G. K. Chesterton, Bernard Shaw, H. G. Wells, Ford Madox Ford, and Joseph Conrad. He got fan letters from Havelock Ellis and Mrs. Bertrand Russell. Manhattan tastemakers like Mark Van Doren, Christopher Morley, and Alexander Woollcott became close friends. 5 5

Yet soon Stout turned his back on experimentation. After the 1929 stock market crash he needed to make money. How Like a God and Seed on the Wind, published by a firm he helped found, sold poorly. His next efforts were less formally adventurous but continued in a vein of erotic provocation. Golden Remedy (1931) traces the sexual frustrations of a philandering concert impresario. In Forest Fire (1933) a park ranger confronts his homosexual impulses when a college student joins his unit. Both books garnered mixed reviews and few sales.

Over the years Stout provided variants of the same explanation for his move to mainstream genres. He took to heart the Collins Test, the distinction between art and entertainment.

These four novels had demonstrated to my satisfaction two things, first—that I was a good storyteller, and second—that I would never be a great novelist. I’d never be a Tolstoy, or a Dickens, or a Balzac…. I might write another dozen or even two dozen novels and they would all get pretty good reception but, two things, they wouldn’t make any large amount of money and they wouldn’t establish me in the first rank of writers. So since that wasn’t going to happen, to hell with sweating our another twenty novels when I’d have a lot of fun telling stories which I could do well and make some money on it. 6 6

His confession echoes a comment of several reviewers who found that his first two books, though technically a bit gimmicky, still managed to tell gripping stories. 7 More than one compared their effect to the suspense generated by detective fiction. 7 More than one compared their effect to the suspense generated by detective fiction. 8 8

Always a fast worker, Stout tried his hand at a political thriller (The President Vanishes, 1934), two comic romances, and detective novels.

There was no thought of “compromise.” I was satisfied that I was a good storyteller; I enjoyed the special plotting problems of detective stories; and I felt that whatever comments I might want to make about people and their handling of life could be made in detective stories as well as in any other kind. 9 9

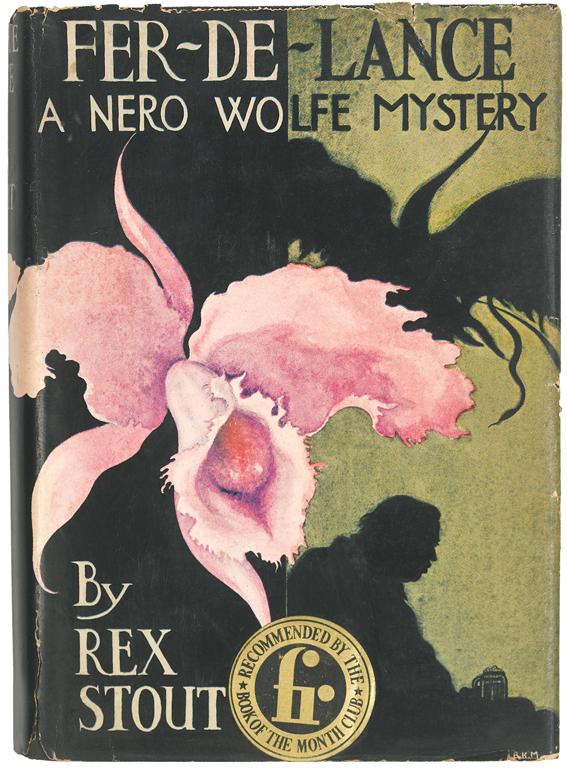

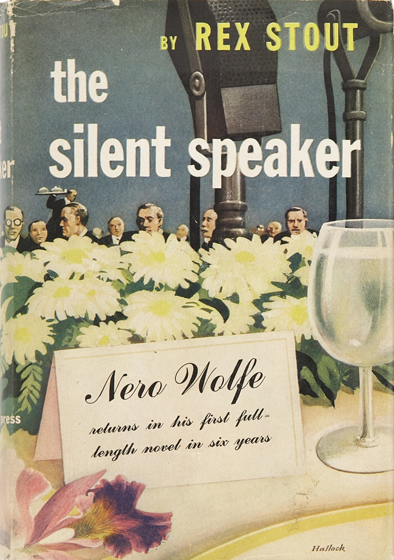

Fer-de-Lance (1934) launched a series centered on Nero Wolfe and Archie Goodwin, and after 1940, Stout would concentrate wholly on them. Their adventures, chronicled sequentially in thirty-three novels and forty short stories and novellas, ended in A Family Affair (1975), published shortly before Stout’s death. 10 10

Stout was a prominent figure in American political culture.. A founder of the left-wing New Masses magazine, he left when it was taken over by Stalinists. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, he mocked Nazi-friendly Congressmen in a book called The Illustrious Dunderheads. He mobilized writers for the war effort, while also fighting publishers to increase writers’ rewards from their work. After the war Stout championed the idea of world government, and he railed against what we’d now call the surveillance state. His biggest-selling Wolfe novel, The Doorbell Rang (1965), attacked the political machinations of the FBI. As an anticommunist liberal he initially supported the war in Vietnam, but he came to despise Nixon as a major threat to democracy. Today he would excoriate Trump.

Many mystery novelists of the 1920s and 1930s tried out modernist techniques, and we might have expected Stout’s exercises in detective fiction to show off his avant-garde ambitions. Instead, coming off some more linear and “straight” novels, Stout did something, in its way, more radical. He carried a central convention of the detective story to a new, almost obsessive limit; he made it newly ingratiating; and in the process he revealed some subtler ways to adapt modernist attitudes to language and narrative to a mass-market genre.

The technique of eccentricity

I understand the technique of eccentricity; it would be futile for a man to labor at establishing a reputation for oddity if he were ready at the slightest provocation to revert to normal action. 11 11

Nero Wolfe

How to fill out a novel’s full expanse? Especially one in a genre with rigid structural conventions? The classic puzzle plot, ideal for a short story, had to stretch itself to book length by means of subsidiary mysteries, more deaths, false solutions, some love interest, and the genius’s disquisitions. Hard-boiled authors might interweave crimes perpetuated by different malefactors (Hammett), pad out descriptions and atmosphere (Chandler), multiply parallels and kinship ties (Macdonald), and sprinkle interrogations across acres of white space (Gardner). Stout had recourse to some of these strategies as well. But coming from “straight” literature, he knew other ways to flesh out the mystery format while still respecting the core conventions.

Stout’s solution to the problem of scale fulfilled a precept Wolfe passed along to Archie: “There is no moment in any man’s life too empty to be dramatized.” 12 Spoken like a true Jamesian (“Dramatize, dramatize!”) and Joycean (Stout thought the Bloomsday chronicle the best novel of modern times). His aim, I think, was to compose a thoroughly conventional detective novel that also provided a character study, created a unique world, spun a yarn in a comic register, and invited us into an adventure in language. 12 Spoken like a true Jamesian (“Dramatize, dramatize!”) and Joycean (Stout thought the Bloomsday chronicle the best novel of modern times). His aim, I think, was to compose a thoroughly conventional detective novel that also provided a character study, created a unique world, spun a yarn in a comic register, and invited us into an adventure in language.

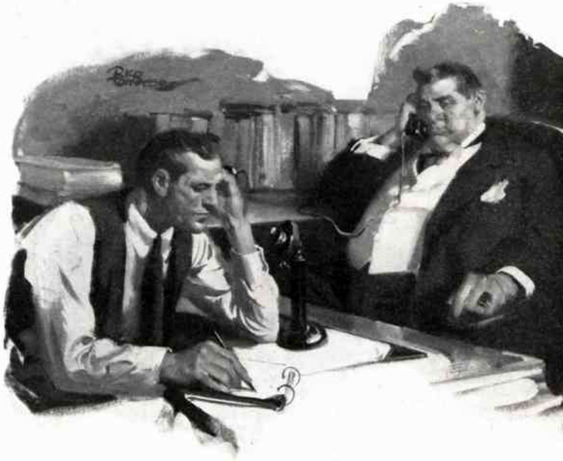

Start with character. Nero Wolfe, weighing in at one-seventh of a ton, lives in a well-appointed brownstone on Thirty-Fifth Street. There he breeds orchids, reads, drinks vast quantities of beer, and dines on meals of rare delicacy. To support his lifestyle he works as a private investigator. But he is the ultimate armchair detective. His central rule of behavior, and the formal premise that founds the series, is that he leaves his home only under extreme necessity.

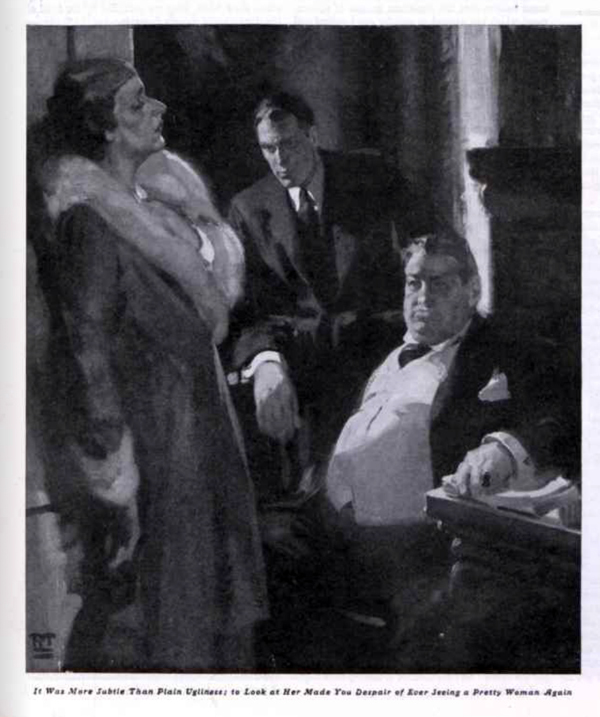

Wolfe’s self-imposed isolation obliges him to employ an assistant, Archie Goodwin, who works as his secretary, making appointments, typing correspondence, and keeping plant records. Archie also acts an investigator and go-between. Hee fetches clients, witnesses, and suspects to meetings. Slender and strong, reasonably handsome, Archie is attractive to and attracted by women of many ages. 13 13

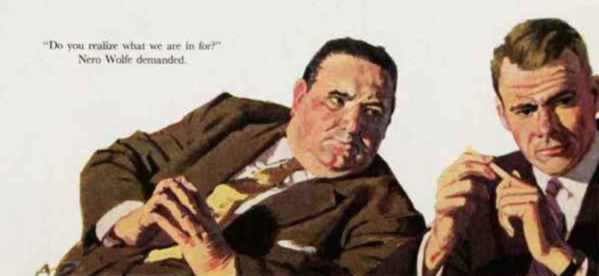

Wolfe is arrogant, lazy, oracular, and imperious. Of Montenegrin origin, he speaks at least six languages and reads voraciously. He is no altruist. He is driven by his need for money and his vaunting self-esteem, although he will also act out of a sense of obligation. His skills in intimidation, evasion, and bluff are considerable. Politically liberal, he has little faith in humans to achieve much collectively.

Above all, he is committed to rationality—or at least as much as a detective in the intuitionist tradition can be. As a boy Stout steeped himself in Doyle, R. Austin Freeman, Wilkie Collins, and other classics, and he admired Agatha Christie, Dorothy Sayers, and even Van Dine. He defended the orthodox detective story as a fairy tale “about man’s best loved fairy”: the belief in the power of reason to serve justice. 14 14

Grunting, pursing his lips, and closing his eyes, Wolfe avoids displays of emotion and recoils from them in others, especially women. His aplomb is that of the detached genius, the “transcendent detective” of classic whodunits. He combines the condescension of Holmes, the cosmopolitan experience of Wimsey, and the gourmet tastes of Philo Vance, with a dash of the fin-de-siècle aesthete: in the early books he claims to be as much an artist as a thinker.

Archie Goodwin, as Wolfe describes him in an appreciative mood, is “inquisitive, impetuous, alert, skeptical, pertinacious, and resourceful.” 15 He is good with weapons and his fists. He can bluff as well as Wolfe, but in an ingratiating, rapid-fire style. While no less sensitive to money than Wolfe—he often has to goad his boss into taking a lucrative case—he has a streak of idealism and fair play, perhaps partly because he hasn’t withdrawn from the world. He has lady friends, chiefly the heiress Lily Rowan, and he enjoys parties. 15 He is good with weapons and his fists. He can bluff as well as Wolfe, but in an ingratiating, rapid-fire style. While no less sensitive to money than Wolfe—he often has to goad his boss into taking a lucrative case—he has a streak of idealism and fair play, perhaps partly because he hasn’t withdrawn from the world. He has lady friends, chiefly the heiress Lily Rowan, and he enjoys parties.

The contrast between Wolfe and Archie has inclined some commentators to see Stout’s accomplishment as a teaming of two prototypical protagonists, the puzzle-solving genius and the hard-boiled man of action. It’s partly true, but in the blend both components are changed.

Traditionally the armchair detective commands center stage. The prototype, Baron Orczy’s Old Man in the Corner, is both protagonist and narrator. Prompted by a young woman, the Old Man recounts his cases in embedded flashbacks. Stout by contrast took the Armchair premise as a formal problem. “Like the restrictions a sonnet writer is held to, Wolfe’s chosen way of life offers a challenge that is fun to meet.” 16 Stout’s solution is to make the assistant participate fully in the action. Archie tells the story, and he is given plenty to do. In some books, Wolfe is offstage for many chapters. 16 Stout’s solution is to make the assistant participate fully in the action. Archie tells the story, and he is given plenty to do. In some books, Wolfe is offstage for many chapters.

Stout defended the use of a Watson as the best solution to the “purely technical problem” of fair play. 17 The writer must present all the information needed to solve the mystery, but the significance of crucial clues must be played down. Systematically surveying viewpoint options, Stout concludes that if we’re attached to the detective’s range of knowledge, suppressing his or her inferences is an obvious cheat. Stout was unwilling to accept the viewpoint shift that Sayers found natural in Trent’s Last Case, although he praised Sayers and Hammett for the way their third-person tales skillfully suppressed the detective’s reasoning. 17 The writer must present all the information needed to solve the mystery, but the significance of crucial clues must be played down. Systematically surveying viewpoint options, Stout concludes that if we’re attached to the detective’s range of knowledge, suppressing his or her inferences is an obvious cheat. Stout was unwilling to accept the viewpoint shift that Sayers found natural in Trent’s Last Case, although he praised Sayers and Hammett for the way their third-person tales skillfully suppressed the detective’s reasoning. 18 18

His preference was clear. A narrating sidekick not only justifies suppressing the detective’s thinking, but it provides creative options. A Watson

keeps the reader at the viewpoint where he belongs—close to the hero—, supplies a foil for the hero’s transcendence and infallibility, and makes the postponement of the revelation vastly less difficult. Also, if your imagination is up to the task of making the stooge a man instead of a dummy, he will be handy to have around in many other ways. 19 19

Stout seized on the opportunities afforded by an energetic, outgoing Watson who could contrast sharply with the great detective while complicating the plot and throwing his own mystifications into the mix. In effect, he turned the Poe-Doyle stooge into a coequal protagonist.

Stout believed that what made Holmes attractive was not his reasoning power but his idiosyncrasies. He admired “the thousand shrewd touches in the portrait of the great detective…. It is stroked in quite casually, without effort or emphasis.” 20 Accordingly, Archie is by turns frustrated and amused by Wolfe’s endless eccentricities, and his reactions go beyond John Watson’s amiable tolerance. Recorded in Archie’s blend of casual mockery, Wolfe’s idiosyncrasies and tantrums become diverting, even endearing. “What makes Wolfe palatable,” Donald Westlake notes, “is that Archie finds him palatable.” 20 Accordingly, Archie is by turns frustrated and amused by Wolfe’s endless eccentricities, and his reactions go beyond John Watson’s amiable tolerance. Recorded in Archie’s blend of casual mockery, Wolfe’s idiosyncrasies and tantrums become diverting, even endearing. “What makes Wolfe palatable,” Donald Westlake notes, “is that Archie finds him palatable.” 21 21

The Great Detective tradition had celebrated one sort of intelligence. Apart from Father Brown and a few others, the genius was purportedly a master of ratiocination, the wizard of little grey cells. Actually, as Leroy Lad Panek has convincingly shown, the brainy detective relies a lot on intuition. 22 In any case, Archie has a different endowment, what we’ve come to call social intelligence. Wolfe threatens, but Archie persuades, wheedles, fibs, flatters, cajoles. Both are suave, but each in his own way, and neither could do the other’s job. 22 In any case, Archie has a different endowment, what we’ve come to call social intelligence. Wolfe threatens, but Archie persuades, wheedles, fibs, flatters, cajoles. Both are suave, but each in his own way, and neither could do the other’s job.

The hardboiled detective tends to be wary, weary, and withdrawn, but Archie the extravert is socially adroit. He’s closer to the fast-talking newshound or salesman of 1930s movie comedies. And he has a more flexible conception of masculinity than what we find in most hardboiled heroes. He doesn’t manhandle women or bully weak men. He can punch, but he prefers shock tactics, yanking a man out of a chair by his ankles, or dragging another man down a hallway on his back. He loves to dance in nightclubs and usually prefers milk to whisky. He almost never gets whacked unconscious. On the one occasion he is given knockout drugs, he wakes up weeping and takes a plausible stretch of time to recover. 23 Then there’s his name: Who calls a tough guy Archie? And Good-win, at that? 23 Then there’s his name: Who calls a tough guy Archie? And Good-win, at that?

Stout admired Hammett enormously, ranking him above Hemingway, but had little patience with the “sex-and-gin marathon” on display in postwar noir novels. 24 In 1950 Stout even parodies the Chandler mode by having Archie impersonate a hardboiled dick. He squeezes a target with phrases like “first-hand dope,” “a nice juicy price,” “a fine goddamn mess,” and references to “bitching up” a plan before he declares, in the noble Marlowe manner: “I have my weak spots, and one of them is my professional pride…. That’s a fine goddamn mess for a good detective, and I was thinking I was one.” 24 In 1950 Stout even parodies the Chandler mode by having Archie impersonate a hardboiled dick. He squeezes a target with phrases like “first-hand dope,” “a nice juicy price,” “a fine goddamn mess,” and references to “bitching up” a plan before he declares, in the noble Marlowe manner: “I have my weak spots, and one of them is my professional pride…. That’s a fine goddamn mess for a good detective, and I was thinking I was one.” 25 Archie never normally talks like this. 25 Archie never normally talks like this.

Archie’s social intelligence makes him shrewd at reading people’s behavior, and Wolfe relies on him for reporting everything he notices. He’s also adept at clue-spotting. Above all, Archie has a roguish skepticism about mystery-mongering. He backs away from the conventions of his trade, veering into the mock-heroic when he asserts that as a detective he is trained to notice shapely figures. With a straight face he reports: “As an example of superior snooping, it was a perfect performance.” 26 He often flatters us when, just before a story’s denouement, he concedes that the reader probably solved the mystery before he did. His ingenuousness is both charming and cunning. 26 He often flatters us when, just before a story’s denouement, he concedes that the reader probably solved the mystery before he did. His ingenuousness is both charming and cunning.

Friday morning, having nothing else to do, I solved the case. I did it with cold logic. Everything fitted perfectly, and all I needed was enough evidence for a jury. Presumably that was what Saul Panzer was getting. I do not intend to put it all down here, the way I worked it out, because first it would take three full pages, and second I was wrong. 27 27

Archie invokes the convention of the false solution, parodies the need to hide the sleuth’s reasoning, expresses solicitude for the reader’s time, and turns the whole exercise into a modest admission of error. Deflate yourself, and you become even more likable.

Because Archie sees Wolfe through grudgingly admiring eyes, Stout can make their ongoing relations, long-term and short, part of the plot. This is another way to “dramatize every moment.” Stout turns the Watson/Holmes interplay into a battle of wits—not just a race to the crime’s solution but a daily game of two men pushing against one another. Archie prods the lazy Wolfe to take cases, quarrels with him about tactics, teases him about his habits, and threatens to quit. (Archie claims to have resigned or been fired dozens of times.).

The petty friction of different temperaments working and living together makes every moment fraught with interest. Both men bicker ingeniously. “You know me, I’m a man of action.” “And I, of course, am supersedentary.” When Archie pushes too far, Wolfe will interrupt: “Shut up.” Archie, though always sensitive to cash flow, is more of an idealist, willing to take a case on principle. “I don’t have to rob corpses to eat and neither do you.” They go through periods of sullen silence, usually broken by the need to cooperate on a case.

Part of the problem is that Wolfe can seem deficit in human feeling. He will invest more emotion in correcting a word choice than in registering a death. When a blunder gives Archie bitter indignation, Wolfe feels humiliated. After Wolfe’s daughter dies, Archie reports: “’She’s dead,’ he said glumly. It always irritated him if I talked like that.” Not that Archie is a wailer. Learning of the death of Wolfe’s oldest friend, Archie starts to tell Wolfe, “but I had to stop to clear my throat.” Both are stoic, but Archie is less jaundiced.

The men will change over the years, but from the start the interpersonal stratagems allow for a fundamental respect and affection. Wolfe admits: “I could do nothing without him” and Archie, while handing an arch-villain a line of patter, seems perfectly sincere in one claim: “He’ll always be my favorite fatty.” 28 More than once Wolfe propels himself out of the house to save his legman. After Archie’s boast about being a man of action, Wolfe reveals that the unconscious Archie rode home in a cab with his head in Wolfe’s lap. 28 More than once Wolfe propels himself out of the house to save his legman. After Archie’s boast about being a man of action, Wolfe reveals that the unconscious Archie rode home in a cab with his head in Wolfe’s lap. 29 29

Wolfe’s idiosyncrasies, Archie’s comparative normality and streak of insubordination, and the first-person narration all bias us toward Archie. Yet Stout balances the scales. Archie at times shows a streak of ethnic prejudice. Early in Too Many Cooks, Archie casually calls the black serving men “smokes.” But Stout is careful to differentiate his white characters by their terms for the servants: “Negroes,” “colored,” “boys,” and, from the most aggressively racist police officials, “niggers.” On this continuum, Wolfe becomes a model. His questioning of the staff shows his knowledge of and respect for African-American culture. After that marathon, and more encounters with racist officers, Archie uses no more epithets, in either conversation or narration. He settles on calling the staff “greenjackets” because of their livery. Such minor-key signals of his changed attitude will become important in the postwar stories.

The handling of racial identity is one extreme example in the ceaseless stream of contrasts that fill out the books. Archie’s impudence versus Wolfe’s stolidity, Archie’s flood of words versus Wolfe’s grunts and lapidary pronouncements, Archie crossing his legs and lifting his eyebrow and Wolfe closing his eyes and wiggling a finger and both of them turning over a hand: every instant is endowed with particularity.

Literary analogies spring to mind: Quixote and Sancho Panza, the phlegmatic and sanguine characters of the Comedy of Humours. Whatever we settle on, it seems evident we are on archetypal terrain. Poirot and Wimsey and Miss Marple are agreeable enough, but they aren’t incessantly, overwhelmingly lively. Archie and Wolfe are. “It is impossible,” wrote cultural historian and Columbia professor Jacques Barzun, “to say which is the more interesting and admirable of the two.” 30 Continuing characters in a series, as Holmes and Watson proved, can hold an audience for generations. In turning to the detective story, Stout brought literary craftsmanship to the task of elaborating the Armchair convention and the Holmes/Watson partnership. Abandoning Serious Literature, he scored a coup any author would envy. He created legends. 30 Continuing characters in a series, as Holmes and Watson proved, can hold an audience for generations. In turning to the detective story, Stout brought literary craftsmanship to the task of elaborating the Armchair convention and the Holmes/Watson partnership. Abandoning Serious Literature, he scored a coup any author would envy. He created legends.

Endless delicious minutiae

The explosion of book and magazine publishing at the turn of the twentieth century encouraged writers to pursue what today we’ve come to call world-building. Treasure Island (1883) and other adventure tales, children’s stories like Alice in Wonderland (1865), and science fiction like The Time Machine (1895) introduced readers to richly furnished imaginary lands.

Unlike the utopias and exotic realms of earlier fictions, these “New Romances” were rendered in novelistic detail. 31 Illustrations, stage versions, and the new medium of cinema made alternative worlds even more palpable. Carrying over a character from book to book had an obvious marketing advantage, but adding a unique terra incognita opened up still more possibilities. A series of books set in a proprietary neverland could sustain an entire writing career, as L. Frank Baum proved with his Oz franchise. 31 Illustrations, stage versions, and the new medium of cinema made alternative worlds even more palpable. Carrying over a character from book to book had an obvious marketing advantage, but adding a unique terra incognita opened up still more possibilities. A series of books set in a proprietary neverland could sustain an entire writing career, as L. Frank Baum proved with his Oz franchise.

World-building showed up in some prestige literature as well. Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio (1919) and Sinclair Lewis’s Zenith novels painstakingly portrayed fictitious American towns. Woolf’s Orlando (1928) was more fanciful, as was James Branch Cabell’s eighteen volumes of tales set in the French town of “Poictesme.” The most ambitious effort at modernist world-building was Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha county, chronicled for thirty years from Sartoris (1929) to The Reivers (1962).

Before Stout, no major writer of detective fiction had tried for such thickly populated milieus. Poirot had sidekicks but scarcely a domicile. The apartment of Ellery Queen and his father was minimal and standardized. Even more sparsely furnished was Perry Mason’s office, and his retinue was a skeleton crew. 32 Philo Vance treated his flat as a gallery of fine art, but did not have a circle of intimates. Lord Peter Wimsey lived a more fully described life, with both a circle of intimates and a detailed biography, provided by Sayers in a privately printed pamphlet. Unusually for a series detective, Wimsey also aged across decades in a more or less chronological sequence of cases. 32 Philo Vance treated his flat as a gallery of fine art, but did not have a circle of intimates. Lord Peter Wimsey lived a more fully described life, with both a circle of intimates and a detailed biography, provided by Sayers in a privately printed pamphlet. Unusually for a series detective, Wimsey also aged across decades in a more or less chronological sequence of cases. 33 33

Sayers’ ambition to fill the Wimsey canvas was doubtlessly indebted to the biggest name of them all. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle contributed to the New Romance trend with his Professor Challenger series, launched in The Lost World (1912), but his major literary creation showcased the world-building impulse in less fantastic surroundings. The Sherlock Holmes adventures settled the great detective and his roommate John Watson in a cozy bachelor redoubt rendered with loving exactitude, from the V.R. bullet-holes on the wall to the strong shag tobacco kept in the Persian slipper.

Stout was no stranger to the New Romance conventions. One of his pulp novels, Under the Andes (1914), a “lost race” story of an underground Inca population, came out of H. Rider Haggard. But we see Stout’s world-building at its most pervasive in his application of the Doyle template of a domestic space whose routines and furnishings could be rendered in refined detail.

The last Holmes story was published in 1927, and Doyle died in 1930. By then an ardent fandom had sprung up among the Manhattan literary elite. 34 Entire books treated Holmes and Watson as actual figures, culminating in Vincent Starrett’s Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, released just as Stout was beginning to write Fer-de-Lance. In his influential introduction to the first two-volume collection of all the stories, Christopher Morley waxed eloquent about the “minor details of Holmesiana” and the “endless delicious minutiae to consider!” 34 Entire books treated Holmes and Watson as actual figures, culminating in Vincent Starrett’s Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, released just as Stout was beginning to write Fer-de-Lance. In his influential introduction to the first two-volume collection of all the stories, Christopher Morley waxed eloquent about the “minor details of Holmesiana” and the “endless delicious minutiae to consider!” 35 The sitting room where clients called, Holmes stretched languidly on the sofa while he scraped the violin, breakfasts on winter mornings, “The game is afoot!”—each scrap of information was to be caressed and cherished. Morley founded the Baker Street Irregulars as an informal dining group. In 1934, the year Fer-de-Lance was published, Morley invited Stout to join the now habitually meeting Irregulars. 35 The sitting room where clients called, Holmes stretched languidly on the sofa while he scraped the violin, breakfasts on winter mornings, “The game is afoot!”—each scrap of information was to be caressed and cherished. Morley founded the Baker Street Irregulars as an informal dining group. In 1934, the year Fer-de-Lance was published, Morley invited Stout to join the now habitually meeting Irregulars.

Stout’s sardonic streak made him resist the cult’s ponderous coyness. “The pretense that Holmes and Watson existed and Doyle was merely a literary agent can be fun and often is, but it is often abused and becomes silly.” 36 Stout famously shocked an Irregulars dinner in 1941 with a remorseless paper asserting that Watson was a woman, probably the wife of Holmes and the mother of Lord Peter. 36 Stout famously shocked an Irregulars dinner in 1941 with a remorseless paper asserting that Watson was a woman, probably the wife of Holmes and the mother of Lord Peter. 37 With friendly humor he called the hagiographical speculations of a Holmes biography “un-canonical and un-Conanical.” 37 With friendly humor he called the hagiographical speculations of a Holmes biography “un-canonical and un-Conanical.” 38 He was bemused by the efforts of the Wolfe Pack, a coterie of admirers who wanted to immortalize his creation through devoted pseudo-scholarship. 38 He was bemused by the efforts of the Wolfe Pack, a coterie of admirers who wanted to immortalize his creation through devoted pseudo-scholarship.

But who can blame them? All the trappings were there. This cantankerous genius had a Watson. Said Watson tantalized us with references to unrecorded cases which, though perhaps not as evocative as the mention of the Giant Rat of Sumatra, still harbored Doyle’s glint of pawky humor: Wolfe, Archie tells us, “sweated the Diplomacy Club business out of Nyura Pronn.” 39 This Watson eventually confessed that the cases (“reports”) were being published thanks to the ministrations of a literary agent named Rex Stout. Some characters had even read the books. 39 This Watson eventually confessed that the cases (“reports”) were being published thanks to the ministrations of a literary agent named Rex Stout. Some characters had even read the books.

References to Archie’s Ohio childhood, Wolfe’s espionage work and family roots in Montenegro, discovery of an estranged Wolfe daughter, a gradual excavation of the past of restauranteur Marko Vukcic: such sporadic revelations coaxed the faithful to ever more patient rereading, ever wilder speculation. What today’s fans call head-canon proliferated. Is Wolfe Mycroft Holmes’ son? Or even Sherlock’s with Irene Adler? Is Archie Wolfe’s son? Or just his cousin? It was inevitable that the foremost Holmes expert, W. S. Baring-Gould, would turn out a treatise on the Wolfe ménage. 40 After Stout’s death Archie would purportedly sign a book correcting the Baring-Gould version and assuring us that everyone was living happily ever after. 40 After Stout’s death Archie would purportedly sign a book correcting the Baring-Gould version and assuring us that everyone was living happily ever after. 41 An alternative history was broached in an interview with an aging Archie, who gave Wolfe a heroic final case. 41 An alternative history was broached in an interview with an aging Archie, who gave Wolfe a heroic final case. 42 42

All this happened because, more than any other writer of the time, Stout carried detectival eccentricity down to obsessive-compulsive granularity. The brownstone on West 35th Street, however recognizably part of Manhattan, became an alternative world, ruled by patterns and behaviors capable of endless fine-tuning.

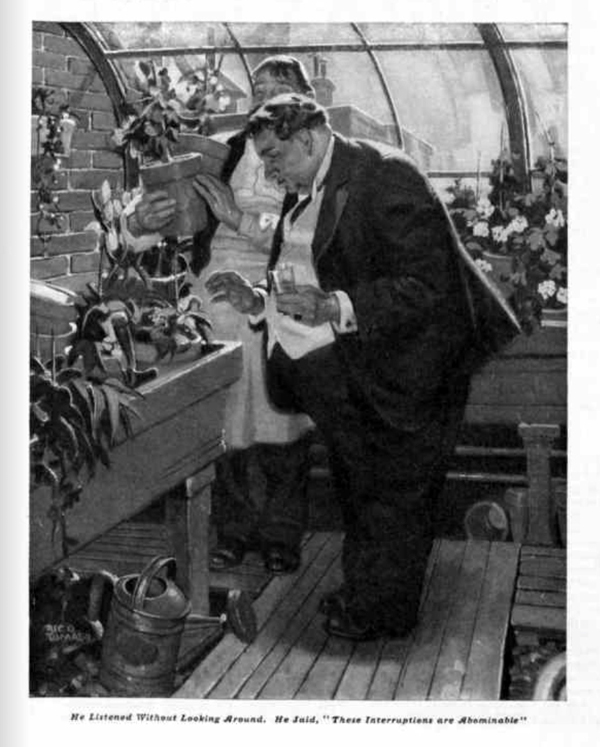

Pages are packed with the arcana of routine. Six days a week at 8:00 A.M., the chef Fritz Brenner delivers Wolfe’s breakfast to his bedroom. At nine Wolfe goes to the rooftop plant rooms for a two-hour session with his orchids and Theodore Horstmann. He descends to his office in an elevator, strides to his desk, and starts his business day. Beer is brought. Checks are signed. Every letter is answered. Archie, who has dusted and tidied up already, reports, or prods, or reads the paper. Lunch comes at 1:15, followed by more office hours.

At four Wolfe returns to his orchids until six. Dinner is around 7:15, and business is never discussed. The evening consists of reading, client meetings, or small intervals of radio or television. Archie may go out on a date, or to a poker game. Wolfe retires late, as does Archie. On Sunday Archie might shoot billiards in the basement while Wolfe watches; otherwise Wolfe visits his plants, reads books and newspapers, and shares a kitchen snack with Archie in the evening. Nobody goes to church.

In the last book of the series, after his most traumatic case, Wolfe contemplates ten days of peace. What will he do? “Loaf, drift…. Read books, drink beer, discuss food with Fritz, logomachize with Archie.” 43 This is a world that tries to keep anything new from happening. 43 This is a world that tries to keep anything new from happening. 44 44

Stout led no less organized a life than his characters. In 1932 he designed and built a modernistic house straddling the New York and Connecticut border. When he was not growing giant pumpkins, provoking political controversies, and teaching crows to talk, he punctually turned out a novel and two or three novelettes every year. These handcrafted stories, written without outlines and never revised after first draft, were sent in immaculate copy to the publisher. No piece consumed more than sixty working days. Erle Stanley Gardner, churning out over a million words a year, called himself the Fiction Factory. Stout was a Fiction Atelier.

The geography of the brownstone is as sharply etched as its routines. There is the greenhouse, where Theodore sleeps, and the basement, where Fritz has his apartment. The main floor consists of hall, front room, kitchen, toilet, dining room, and office. Upstairs is Wolfe’s bedroom, very large and striking, with its yellow telephone and black silk coverlet. In Archie’s homier quarters we find three chairs (who ever visits?), a tile-top table, a photo of his parents, and an African violet on the windowsill. Both the second and third floor contain guest rooms. In a back garden Fritz grows tarragon and chives.

As the years go by, we learn more and more. Seven front steps lead to the door, which has a one-way glass and a chain bolt. Pressing the button activates a doorbell, which replaced the buzzer of the first book. The best chair in the office is red, with a small table positioned at a client’s elbow for easy check-signing. At one end of the office is a big globe (first two feet, then three feet in diameter) that Wolfe likes to gently spin. On his desk is a thin gold strip that he uses as a bookmark. One drawer is reserved for the beer-bottle caps Wolfe occasionally counts. There’s a safe, a cabinet for files, and built-in bookshelves holding hundreds of volumes. A painting conceals a peephole. Eventually the office and front room become soundproofed.

We could specify forever. The chain bolt is two inches long, the painting depicts a waterfall, the study has eight light fixtures. A bar cart draped with a yellow linen tablecloth is wheeled out to serve visitors. The office floor is covered with an ever-changing rug, Persian or Armenian. Under Archie’s bed is a gong wired to go off if Wolfe’s room is approached. The orchids bloom in three rooms (moderate, tropical, and cool), with a potting room at the end. 45 45

Stout’s casually stroked-in details pay homage to the master. Morley called the Holmes stories “this great encyclopedia of romance,” but another detective novelist, Edmund Crispin, pointed out that the Wolfe digs are “so encyclopedic and thoroughgoing that the Holmes-Watson ménage on Baker Street, in comparison, is reduced to the sketchiest of shadow-shows.” 46 46

Revising the conventions

A richly furnished milieu to match the regimen of routines: these self-imposed limits carry echoes of High Modernist severity of space and time (Ulysses, Mrs. Dalloway) and their middlebrow counterparts (Twenty-Four Hours, Dangerous Corner). But the constraints also allow Stout to quicken every moment “in any man’s life.” Habits and habitat are dramatized through details. Apart from characterizing his Holmes and Watson in full array, Stout uses world-making to fill out the novel’s length. In the process, he can enliven central conventions of the classic puzzle mystery.

For instance, the Armchair premise motivates not only Archie’s excursions but the need to hire other operatives who become fixtures of Wolfe’s World. Saul Panzer the unassuming but exceptional free-lance, is flanked by sturdy Fred Durkin and overconfident Orrie Cather and a couple of other sides of beef, along with Dol Bonner of the caramel eyes. These operatives become helpers, occasional obstacles, and Archie’s comrades in arms. They allow Stout to keep offstage all the boring Q & A, all the tailing and stakeouts and alibi-checking that fill up the more plodding hardboiled books and police procedurals. As needed, a helper can be promoted to client (as Orrie is in Death of a Doxy) or conspirator (as in The Doorbell Rang). Outsourcing the humdrum tasks of detection, Archie and Wolfe can concentrate on confronting the key suspects, bantering with one another, and occasionally discovering a corpse.

Similarly, Wolfe’s willful immobility recasts the convention of the bumbling police. Archie can be summoned to headquarters and even jailed as a material witness, but Wolfe can usually avoid that fate. The cops must come calling. Wolfe can subject Inspector Cramer and Sergeant Purley Stebbins to his schedule and, when he finally grants them an audience, intimidate, bargain, and dodge accusations in comfort.

Once more the filigree detail flows in. Archie will watch amusedly from his desk, swiveling to take notes or do some typing. (“I made a note to grin when I got the time.” 47) Cramer must sit fuming in the big red chair and sooner or later he will fling his unlit cigar at Archie’s wastebasket (and will miss). One thing that makes the novels endlessly rereadable, as the fans attest, is looking forward to these rituals, and enjoying how Archie renders them this time. Will Cramer call him Archie or just Goodwin? Will he let Archie take his coat in the hall? Will Archie describe the reddening of Cramer’s face, or his teeth clenching his cigar, or where he situates his fanny on the chair? 47) Cramer must sit fuming in the big red chair and sooner or later he will fling his unlit cigar at Archie’s wastebasket (and will miss). One thing that makes the novels endlessly rereadable, as the fans attest, is looking forward to these rituals, and enjoying how Archie renders them this time. Will Cramer call him Archie or just Goodwin? Will he let Archie take his coat in the hall? Will Archie describe the reddening of Cramer’s face, or his teeth clenching his cigar, or where he situates his fanny on the chair?

The personal habits of the Great Detective have always helped flesh out the standard plot and build fan loyalty. In 1941, in one of the milestones of critical writing in the genre, Howard Haycraft warned the would-be author that readers want to know everything about our heroes, including what they eat for breakfast—“though we mustn’t be told too often.” 48 48

He likely had Stout in mind. Stout delineates every exotic dish served at Wolfe’s table, every sandwich Archie gobbles in custody, even Cramer’s stomach-turning snack of salami and buttermilk. Groceries, brought home by Fritz or picked up in flight from the police, are lovingly itemized. The Continental Op briefly notes his abalone soup and minute steak, but Archie dwells on his dining options.

I had had it in mind to drop in at Rusterman’s Restaurant for dinner and say hello to Marko that evening, but now I didn’t feel like sitting through all the motions, so I kept going to Eleventh Avenue, to Mart’s Diner, and perched on a stool while I cleaned up a plate of beef stew, three ripe tomatoes sliced by me, and two pieces of blueberry pie. 49 49

No moment too empty to be dramatized: Archie invokes another Wolfe domain, Rusterman’s, only to head to the diner counter and indulge the Ohio boy’s fondness for comfort food. The “sliced by me,” reiterating Archie’s impulse to act, is a touch nobody but Stout would include.

Building this unique world obliges Stout to alter the role of detecting as a profession. Wolfe runs a business, and he does it better than almost any of his fictional counterparts. As the boss (which Archie is never allowed to call him), Wolfe adheres to the hours he has fitted into his schedule. He scrupulously answers correspondence, with Archie taking dictation in his own bespoke shorthand. Archie the legman is also the firm’s bookkeeper, and he constantly reports income, losses, and terms of payment.

Philip Marlowe accepts what business he can scrape up, while Perry Mason can afford to take indigent clients, even a caretaker’s cat. Wolfe and Archie rely on high-end customers. After all, as Archie confides in 1950, maintaining the household costs $10,000 per month, and Wolfe must pay top income-tax rates. Fees of $50,000 aren’t unusual, and in 1965 one retainer comes to twice that. True, some cases yield no payment, and Archie may nudge Wolfe to take on small-dollar business on principle. But then, if only to save face, Wolfe will declare that his self-esteem, or the need to evade jail, overrides the loss of income.

Wolfe’s fee structure means that the clientele comes mostly from the plutocracy and the professions—lawyers, professors, media producers, company executives, and a surprising number of writers and publishers. The hardboiled dicks like to expose affiliations between the upper crust and organized crime, but Wolfe and Archie seldom do. (Only the master adversary Zeck runs a racket, and even he operates chiefly as a CEO.) Wolfe deals with crime in the suites, not the streets. Typically a financial or personal problem leads to a murder, and Wolfe and Archie are obliged to solve the crime in order to collect payment for the original assignment. In one book Wolfe calls this “effecting a merger.” 50 50

More than most detectives, Wolfe takes on clients in teams. He may be retained by a committee delegated to manage a crisis, or representatives of a firm or professional association, or a family of heirs, or a band of old college classmates. Accordingly, the question-and-answer scenes of the classic mystery get recast as business meetings, or what Archie sometimes calls conferences. Wolfe summons a group of people with stakes in the matter, and the result shows how Stout manages to dramatize the quizzing that is the mainstay of the classic puzzle. The open-ended quality of these sessions made Jacques Barzun call it Wolfe’s seminar method. 51 51

“I doubt I’ll have a single question to put to any of you, though of course an occasion for one may rise. I merely want to describe the situation as it now stands and invite your comment. You may have none.” 52 52

Refreshments are served—more detailing of beverages and preferences—and participants are free to examine Wolfe’s library and furniture. Chandler, who had been an oil-company executive, confessed he had trouble writing scenes with more than two people, but Stout, who founded a successful company, excelled in rendering roundtable discussions.  53 53

The mercantile tenor of the books also reshapes the conventional denouement, the gathering of all the suspects. Archie, reflecting as usual on the artifice of detective conventions, calls these Wolfe’s parties or charades. Theatrical they often are, but they don’t have the inexorability of Ellery Queen’s “exercises in deduction.” Often Wolfe’s evidence is flimsy and he must provoke the guilty party to self-betrayal. Assembled in Wolfe’s office, usually under the eyes of Cramer and Stebbins, the principals are lectured, hectored, bluffed, and misled. After the book’s procession of meetings presided over by Wolfe, the climax seems less a blinding revelation than a boardroom power play, even a hostile takeover.

The practicalities of business thus help extend the plots, surrounding the mystery in—what else?—more routines. Similarly, two of Wolfe’s avocations get expanded to novelistic length. His passion for food is the basis of Too Many Cooks (1938), in which murder takes place at a ceremonial gathering of master chefs. Wolfe’s solution earns him a rare secret recipe. As for orchids, they provide Stout several premises, most extensively in Some Buried Caesar (1939). Here Wolfe attends an upstate agricultural exhibition in hopes of trouncing a rival orchid grower. Wolfe wins a medal and three ribbons and almost incidentally forces a killer to commit suicide.

All this local color adds up to the pleasure of predictability, the routines and milieu we know so well. Just as important, though, is the thrill of a tidy world disrupted. The brownstone may be threatened by a bomb or a snake, the plant rooms strafed by machine-gun fire, the office’s Persian rugs soaked with a victim’s blood. Wolfe’s adherence to schedule is broken by emergencies, not least the death of friends. Nearly every story includes Archie’s assertion that in this case some custom or other was breached for the first time.

Actually, Wolfe abandons his armchair far more often than we’d expect. He leaves home no fewer than thirty times in seventy-three stories. Sometimes the pretext is ludicrous (playing Santa Claus at a party?), but it’s often significant: a meeting of gourmets, an orchids competition, an attempt to rescue Archie, a contribution to the war effort, a ruthless scheme to eliminate a master criminal, and a surreptitious trip to Montenegro to avenge two deaths. He justifies rule-breaking as supremely rational. “One test of intelligence…is the ability to welcome a singularity when the need arises, without excessive strain.” 54 54

Detective stories usually make investigations routine; here investigations shatter routines. Thereafter the plot must work to restabilize Wolfe’s world—coordinating the “family” (Fritz, Doc Vollmer, the lawyer, the operatives), or setting up surrogate spaces. Wolfe holds court in a spa in Too Many Cooks and in an inn’s guest bedroom in Some Buried Caesar. If all detective stories are, as Auden suggested, about restoring Eden, the vividly etched all-male paradise at West Thirty-Fifth Street is made especially worth redeeming.

You can argue that Stout’s near-maniacal loading of every moment with world-building value led him to shambolic plotting. Despite his enjoyment of the “special problems” of designing a detective story, critics and fellow novelists complained that the Wolfe plots are diffuse, inconsistent, and riddled with coincidence. Sometimes Archie dumps background data and timetables in front of us with a lordly contempt for the rules of the game. “I give it here…not for you to exercise your brain—unless you insist on it—but for the record.” 55 55

The stage is overcrowded. Apart from the repertory company, there may be a dozen clients and suspects, and many are sketchily characterized. Since Wolfe leaves alibi-breaking to the police, the standard mechanism for eliminating suspects (and stretching out the book) isn’t operative. Often, anyone could have committed any of the crimes in question. Indeed, in the hit-and-run murders that crop up frequently, the adult population of Manhattan might need to be rounded up. Yet we tend to trust the Wolfe-Archie assumption that the closed circle of suspects characteristic of the classic puzzle holds good here too.

Many of the plots have dead spots, days or weeks of waiting for something to develop. Pressured, Wolfe may run an advertisement or assemble suspects and make idle threats to provoke impulsive mistakes. Or events may crowd in to force a finale. Murders tend to pile up in later chapters, but they don’t necessarily clarify the case. Wolfe’s conclusions are often risky intuitions, underdetermined by evidence that would convince a jury. Hence the frequent recourse to extralegal pressures that would give even Perry Mason pause. Wolfe will coolly order burglary, send out anonymous messages, and press the guilty party to commit suicide.

In even more severe violation of fair-play conventions, later phases of the plot are likely to hide crucial information from Archie, and us. Wolfe often dispatches Saul, now a Jamesian ficelle, to unearth information that will prove decisive in the final “conference.” This hugger-mugger pays perverse tribute to the need to restrict the Watson viewpoint, but it distracts from the articulation of the puzzle.

Stout admitted that his own strictures on fair play were often violated by the best mystery-mongers. 56 Doyle ended his career by concocting “preposterous” mysteries, but that didn’t lessen the magnetism of the Holmes/Watson relationship. 56 Doyle ended his career by concocting “preposterous” mysteries, but that didn’t lessen the magnetism of the Holmes/Watson relationship. 57 Accordingly, Stout never wanted to sacrifice character byplay to the exigencies of the genre. Wolfe’s dodgy shortcuts, implausible as they sometimes are, create fine scenes. They generate suspense, offer Archie new challenges, allow Wolfe to earn his fee, prove his cunning, and provoke Cramer’s wrath. Likewise, keeping Archie in the dark at the climax adds value, tightening household friction and giving him occasion for eloquent complaint. 57 Accordingly, Stout never wanted to sacrifice character byplay to the exigencies of the genre. Wolfe’s dodgy shortcuts, implausible as they sometimes are, create fine scenes. They generate suspense, offer Archie new challenges, allow Wolfe to earn his fee, prove his cunning, and provoke Cramer’s wrath. Likewise, keeping Archie in the dark at the climax adds value, tightening household friction and giving him occasion for eloquent complaint.

So the shagginess of plotting in the Wolfe saga can be seen as a cost, but also a benefit of the decision to weight world-making. In a genre that depends on what Stout called “designed concealment,” what better camouflage than a sparkling surface? 58 A critic sympathetic to Stout noted of the late novels: “One wonders if Mr. Stout has all but given up writing detective stories for the weirdly challenging sport of stretching short stories into novels. It would seem so, but the padding is pretty entertaining.” 58 A critic sympathetic to Stout noted of the late novels: “One wonders if Mr. Stout has all but given up writing detective stories for the weirdly challenging sport of stretching short stories into novels. It would seem so, but the padding is pretty entertaining.” 59 That’s because it seeks to dramatize what other writers treat as filler. 59 That’s because it seeks to dramatize what other writers treat as filler.

Venom in the desk drawer

Nearly all the typical Stout dynamics are on display in the first book, Fer-de-Lance of 1934. The esoteric title distinguishes it from the run-of-the-mill detective novel of the moment. 60 Stout’s trust in the reader’s patience is apparent in the fact that the viper doesn’t appear or get mentioned for over two hundred pages. 60 Stout’s trust in the reader’s patience is apparent in the fact that the viper doesn’t appear or get mentioned for over two hundred pages.

I tried it again. “Fair-du-lahnss?”

Wolfe nodded. “Somewhat better. Still too much n and not enough nose.”

Stout takes the opportunity to contrast Heartland Archie and worldly Wolfe while letting smart readers enjoy linguistic play and instructing the rest of us in pronunciation. Of his next book a reviewer would write: “Mr. Stout adorns his tale with lots of good writing adapted to highbrow and lowbrow alike.” 61 61

Fer-de-Lance, rather long for a mystery of its day, presents a cascade of coincidences and delays. The murder isn’t revealed as such until the fourth chapter. Not until the twelfth, over a hundred and fifty pages in, do we learn that the victim was not the intended target. Red herrings include a golf bag that seems missing but isn’t. One witness is questioned at intervals across the book, and she eventually admits something crucial she could have provided much sooner. Another key witness is conveniently out of town for the first two hundred pages; upon returning, he provides the solution. Stymied, Wolfe forces a crisis by running a newspaper advertisement, but he needs another sixty pages to force the culprit to kill himself, with the death of the original target as collateral damage.

These plot zigzags are enfolded in the minutiae of Wolfe’s world. The opening plunges us right in.

There was no reason why I shouldn’t have been sent for the beer that day, for the last ends of the Fairmont National Bank case had been gathered in the week before and there was nothing for me to do but errands, and Wolfe never hesitated about running me down to Murray Street for a can of shoe-polish if he happened to need one. But it was Fritz who was sent for the beer. Right after lunch the bell called him up from the kitchen….

Beer, Wolfe, Fritz, a successful case, an order issued by the employer, and household custom are all breezily taken for granted from the start. In an ordinary book, this would be a more typical middle chapter. The mystery isn’t Whodunit? but What’s the big deal about the beer? The scene centers on Wolfe (the “Nero” isn’t supplied for three chapters). Archie hints at his bulk but concentrates on chronicling his eccentric thoroughness in sampling the entire array of legal 3.2 beer. “None shall lack opportunity.” He could have waited; Prohibition is only a few months from ending.

We approach the main action at several removes. Fred Durkin brings in Maria Maffei, whose brother Carlo is missing. Maria leads Archie to the key witness Anna Fiore, whom he brings back to the office. Based on a phone call she overheard, Wolfe concludes that a man who dropped dead on a golf course has likely been murdered. But Maria is poor, so now Wolfe has to find someone to pay him to take the case. As in other books, a bona fide client will cover the costs of justice.

As Wolfe’s involvement deepens, the first chapters provide demonstrations of personal styles. Archie’s dogged but fruitless questioning of Anna in the boarding house is contrasted with Wolfe’s patient conversations with her in the office. Archie takes two hours, a period Stout renders in a paragraph of summary, but Wolfe pursues her for five hours, with the crucial exchanges dramatized in several pages. “It was beautiful,” Archie reports. The questioning reveals that the missing brother is indirectly involved in the golfing death.

Swerving the spotlight, Stout gives Archie his own big scene. He delivers to the White Plains investigators Wolfe’s $10,000 bet that the death was a murder and that poison will be found if the body is exhumed. This is the first display of Archie’s gifts for politely annoying the hell out of authorities with a string of arguments, threats, and forced choices. Wolfe’s confidence that he can turn the case to profit gets amplified by Archie’s grinning effrontery. Later we’ll discover that they’re also settling an old score with this District Attorney, who among other transgressions has married money.

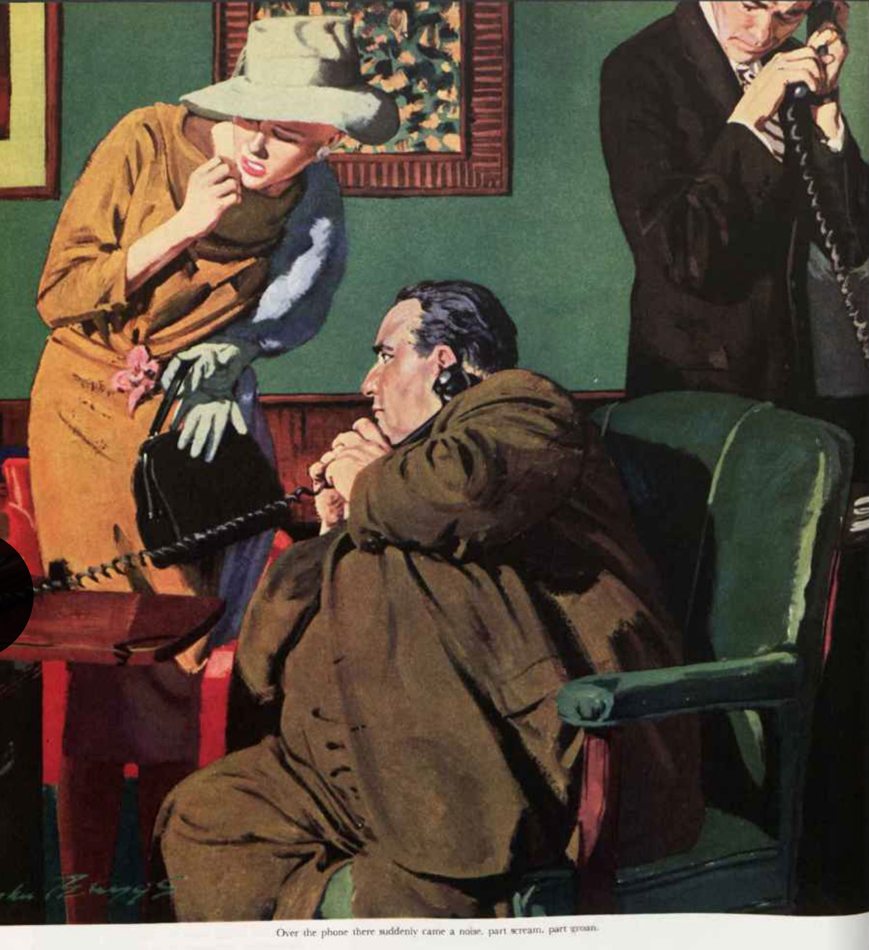

The first six chapters are occupied with these business maneuvers. A hardboiled novel would begin with the murder victim’s daughter visiting the office, but here that comes eighty pages in. She’s been lured by Wolfe’s newspaper advertisement, itself the result of his accidental discovery of the murder. Once Wolfe is hired, Archie can rush toward the action he enjoys, and we get the characteristic cycle of his excursions, his reports to the boss, his tapping his newspaper sources, and the conferences with police and suspects. The hero-worshipping tone in the early chapters gives way to exasperation, as we’re introduced to the rhythm of Wolfe stubbornness and Archie badgering that will pervade the series to come.

The opening stretches also display how Wolfe uses his supersedentary role to play puppeteer. He bends everyone to his agenda, with Archie summoning people to meals and interrogations while horning in on their private lives. The Armchair premise, driven by Wolfe’s self-centeredness, ultimately determines how he’ll settle the case. By triggering the killer’s murder/suicide, he will never have to bestir himself to testify in court.

Besides familiarizing us with the routines and introducing us to the protagonists’ personal styles, the opening stretches of Fer-de-Lance set in place distinctive features of Stout’s prose. The first sentence is a sinuous but perfectly compact evocation of immediate circumstances and Wolfe’s imperious habits, and perhaps it hints at Archie’s annoyance at not getting the beer assignment. More generally, Archie’s vulgar zest and Wolfe’s pompous pronouncements dominate these sections, but Fer-de-Lance establishes a finer-grained pattern of echoes and refrains that show something just as distinctive in Stout’s achievement.

Other detective writers adapted modernist schemas to mystery through time shifts, viewpoint switches, replays, dossiers, grids, and the other techniques. Stout was far more orthodox on these dimensions, though his embedding of exposition and flashbacks is exceptionally smooth. More salient are the ways he brought modern novelistic finish to the detective story, bending Archie’s vernacular to verbal patterning that had become part of mainstream literary technique.

Take a straightforward instance. Early in Fer-de-Lance Wolfe says that Archie collects facts but has no “feeling for phenomena.” Wolfe tells Maria that Carlo’s disappearance is only a fact. Apparently it doesn’t become a bona fide phenomenon until physical clues let him grasp Carlo’s role in the murder.

The phrase sounds good, but Archie, having looked up “phenomenon,” suspects Wolfe is just parading. Yet Archie can’t let it go. He will defend his hunches about one suspect as proving he too can pick up on “phenomena.” When no suspect seems a prime candidate, Archie reflects that Wolfe may need to “develop a feeling for a new kind of phenomenon: murder by eeny-meany-miney-mo.” Later, Archie confronts Wolfe and starts talking “just for practice”:

“The problem is to discover what the devil good it does you to use up a million dollars’ worth of genius feeling the phenomenon of a poison needle in a man’s belly if it turns out that nobody put it there?”

In the book’s closing lines, Wolfe says he’s willing to take responsibility for the two deaths that conclude the action and keep him out of court. Archie replies:

“Now, natural processes being what they are, and you having such a good feeling for phenomena, you can just sit and hold your responsibilities on your lap.”

“Indeed,” Wolfe murmured.

The “phenomena” phrase, exploited for different resonance, recalls the taglines that echo through 1930s films. As woven into a book’s narration, though, they also descend from literary tradition. Jane Austen, whom Stout considered “probably, technically,” the greatest novelist, sends the word “likeness” chiming significantly through Emma. 62 After Wagner, artists in many media made more self-conscious use of motivic play, and it was a prominent strategy of modern literature and drama. 62 After Wagner, artists in many media made more self-conscious use of motivic play, and it was a prominent strategy of modern literature and drama.

The most proximate source for Stout was perhaps Ulysses, with its refrains of “Met-em-pike-hoses,” “Your head it simply swirls,”’ and many more. Similar strategies are at work in Conrad and Shaw. 63 Stout’s first “art novel,” How Like a God, introduces the rare word “vengeless” very early and brings it back twice across the book to emphasize the protagonist’s passivity. 63 Stout’s first “art novel,” How Like a God, introduces the rare word “vengeless” very early and brings it back twice across the book to emphasize the protagonist’s passivity. 64 64

Stout relies heavily on refrains, both within and across books. Take “satisfactory,” Wolfe’s highest term of praise. When Wolfe repeats it in a burst of praise, Archie takes the moment as record-breaking. In another book, Archie applies it to their guest: “That girl would have been a very satisfactory traveling companion.” The word recurs at intervals and returns on the last page, where Archie works off his anger by punching an obstreperous guest whose “hundred and ninety pounds…made it really satisfactory.” 65 By The Final Deduction (1961), Archie can introduce the word in his narration and conversation before Wolfe finally resorts to it. 65 By The Final Deduction (1961), Archie can introduce the word in his narration and conversation before Wolfe finally resorts to it.

Similarly, the later novels reiterate Wolfe’s objections to “contact” as a verb and his insistence that “quote/unquote” is a barbarism. Erle Stanley Gardner’s repetitions from book to book are bland filler, while Stout’s serve more literary ends of characterization and patterning, while quietly assisting world-building.

A refrain limited to a single book is seldom a clue to solving the mystery. More often it will mark characters. A woman is called a snake by her father-in-law, and Archie riffs freely on the word when he encounters her. A showgirl in Death of a Doxy (1966) can recite the alphabet backward, a skill that gets deflated at the climax when she’s tongue-tied. 66 The refrain can also create associative links, as in Before Midnight (1955), where “crap” hooks up with “memory” and “drink.” Most often, as we’ll see, the refrain is exploited for comic possibilities. 66 The refrain can also create associative links, as in Before Midnight (1955), where “crap” hooks up with “memory” and “drink.” Most often, as we’ll see, the refrain is exploited for comic possibilities.

Fer-de-Lance doesn’t yet deploy “satisfactory” in the Wolfean sense, but it sprinkles in refrains like “lethal toy,” “genius,” “artist,” and “lovin’ babe!” and pauses for a debate about the slang use of “ad” for “advertisement.” Sometimes the iterations are closely packed, knitting together dialogue exchanges, but they can also recur at a distance. Archie reflects that somehow Wolfe could be called elegant, and when the obstinate witness Anna behaves with poise four pages later, he grants: “She was being elegant. She had caught it from Wolfe.” Two hundred pages later, when Archie induces Anna to sign the decisive statement, he notices that their first client Maria has changed dramatically. “She looked elegant.” Evidently she has caught it from Anna.

Or take foreshadowing. The classic detective story scatters clues deceptively, creating a sort of disguised foreshadowing. The gun hanging on the wall in act one might not be the murder weapon; something else is, but it will be barely mentioned or deceptively described. A more self-consciously literary novel can foreshadow action through imagery rather than plot-dependent clues and hints. For instance, the beer bottles brought in to Wolfe on the first page of Fer-de-Lance remain as props in later office scenes, as does the desk drawer in which Wolfe stores his opener and bottle caps. At the climax, that drawer is opened.

“Look out!”

Wolfe had a beer bottle in each hand, by the neck, and he brought one of them crashing on to the desk but missed the thing that had come out of the drawer…. I was ready to jump back and was grabbing Wolfe to pull him back with me when he came down with the second bottle right square on the ugly head and smashed it flat as a piece of tripe.

The beer and the drawer are carefully planted, but most novelists, detectival or not, wouldn’t proffer a remark two hundred pages earlier, long before we have heard anything about vipers and have met any suspects.

I looked at Wolfe and back again at the pile on the floor. It was nothing but golf clubs. There must have been a hundred of them, enough I thought to kill a million snakes. For it had never seemed to me that they were much good for anything else.

I said to Wolfe, “The exercise will do you good.”

Rereading this passage with the knowledge that a snake will indeed pop up in the office and Wolfe will dispatch it furiously gives Archie’s serpent massacre and his teasing comment weight as items of literary artifice.

Stout is composing his first Wolfe book sentence by sentence. He isn’t a minimalist like Gardner or a simile-monger like Chandler or Macdonald, but rather a weaver of softly echoing imagery. These motifs supplement world-making and become another means of dramatizing each moment.

The fortunes of Pfui

If you resent the vulgarity of Mr. Goodwin’s jargon I don’t blame you, but nothing can be done about it.

Nero Wolfe 67 67

A vein of comedy runs through mysteries of the 1920s. Lord Peter warbling about a body in the bath is only the most obvious instance of the silly-ass characterization that crept into the puzzle form. London’s Bright Young Things took up sleuthing in A. A. Milne’s Red House Mystery (1922), while Margery Allingham’s Albert Campion, with his sidekick former burglar Magersfontein Lugg, began as a parody of Wimsey. At a loftier level, Sayers, Anthony Berkeley, and others had thought that the detective story could legitimize itself by becoming a “novel of manners,” with the mild satire that that term implied. A rougher, more sarcastic humor could be found in Hammett and other hardboiled authors, at about the same time slick magazines were running folksy tales of comic detection. 68 68

Film had offered some comic crime efforts as well. Howard Hawks turned Trent’s Last Case (1929) into a Charley Chase farce, and Seven Keys to Baldpate (1930) revived the perennially popular stage mystery. But the influence of screwball comedy had the strongest effect. The film of The Thin Man (1934) showed the lively possibilities of socialites solving murders in the midst of high-end shopping, fine dining, and tipsy chatter. Even the hard-bitten Perry Mason of the novels became the louche drunk of The Case of the Lucky Legs (1935).

Stout had a funny side. He wrote humorous short stories in his pulp days, and after the second Wolfe novel, The League of Frightened Men (1935), he published a light romance, O Careless Love! (1935) about three schoolmistresses looking for adventure in New York. Later came Mr. Cinderella (1938), a Capraesque novel about a bashful inventor of kiss-proof lipstick. Stout’s first published article, a satiric guide to seducing women, was published in a sniggering misogynist anthology, and in the same year he gave the Saturday Evening Post a boyhood memory of being chased by a bull. 69 Far more ambitious was his effort in the Wolfe books to meld the conventions of the post-Doyle detective story with vernacular American comedy. 69 Far more ambitious was his effort in the Wolfe books to meld the conventions of the post-Doyle detective story with vernacular American comedy.

Stout claimed to have hated movies, but he didn’t disdain pratfalls and funny situations that are easy to visualize. Some Buried Caesar (1939) begins with Archie crashing the sedan, with Wolfe jouncing in the back seat. As they start out to a nearby farm, Wolfe notes that they’re crossing a cow pasture. “Being a good detective, he produced his evidence by pointing to a brown circular heap near our feet.” Soon, though, a bull charges them. (“He started the way an avalanche ends.”) Archie runs to the fence and vaults clumsily over, to the amusement of two young women watching. Meanwhile Wolfe has somehow found a perch on a boulder in the field and is now standing as still as a statue, awaiting rescue.

Later in the book, a twenty-five-page interlude finds Archie jailed with a despondent conman named Basil. When Wolfe visits, it’s not just to console Archie but to get ready cash. As Wolfe starts to recall his experience in a Bulgarian prison, Archie shuts him up by shouting through the bars, “Oh, Warden! I’m escaping!” Lily Rowan, whom we first meet in the book, calls on Archie as well, using the nickname that will always recall the bull episode, “Escamillo.”

All this is the prose equivalent of a screwball comedy. So too is the moment in Champagne for One (1958) when Wolfe, attacked by a murderous woman, rears back and kicks her chin. One scene in And Be a Villain (1948) could be a script for a 1940s satire of bobby-soxers. Wolfe is trying without much success to question a teenager who has started a fan club. Her idol is “simply utterly,” the girl explains:

“You see how that is. The old ego mego.”

You can see why I’d like to be fair and just to her.

Wolfe nodded as man to man.

He asks her about the soft drink her idol peddles, and she replies: “Oh, I guess I adore it.” Wolfe wonders if there’s pepper in it. “I don’t know, I never thought. It’s a lot of junk mixed together. Not at all frizoo.”

“No,” Wolfe agreed, “not frizoo.” 70 70

This example reminds us that the slapstick episode launching Some Buried Caesar is atypical. Stout’s comedy is largely verbal, a torrent of wisecracks, teasing, mimicry, malapropisms, and barefaced silliness. You have to be fast. Wolfe can occasionally crack a mild joke, often at Archie’s or Cramer’s expense, and once in a great while Cramer fires back. When Archie says he can start breathing again, Cramer says: “The day you stop I’ll eat as usual.” (Food again.)  71 Lieutenant Rowcliff, the only thoroughly bad cop, wears the mark of Cain in this chattering crowd: he stutters. Of course Archie enjoys provoking this reaction. He has timed how long it takes. 71 Lieutenant Rowcliff, the only thoroughly bad cop, wears the mark of Cain in this chattering crowd: he stutters. Of course Archie enjoys provoking this reaction. He has timed how long it takes.

Doyle recalled, somewhat unfairly, that Watson never showed a gleam of humor, but Archie personifies fun. In nearly every story somebody accuses him of clowning. Herewith samples.

To Lily Rowan: “You’re always right sometimes.”

To Wolfe, after a stretch of inactivity: “I’m just breaking under the strain of trying to figure out a third way of crossing my legs.”

To Wolfe, who mentions when he went out in the rain. “Yeah. Will I ever forget it. There was such a downpour that the pavements were damp.”

To O’Hara, bearing a message from Wolfe: “He said to tell you you’re a nincompoop, but I think it would be more tactful not to mention it, so I won’t.”

To a visitor who wants to see Wolfe: “You C A N apostrophe T, can’t. Don’t be childish.”

To Wolfe, who opens a book instead of tackling a case and instructs Archie to order some orchids: “Right. And Sitassia readu for you and Transcriptum underwood for me.”

To a suspect: “You’re too careless with pronouns. Your hims. Your first him’s opinion of your second him is about the same as yours.”

The man is shameless. “I agree with whoever it was, millions for de-femmes but not one cent for tribute.” A thug decides to lecture Archie about showing too much humor. “Someday something you think is funny will blow your goddamn head right off your shoulders.” Esprit de l’escalier makes Archie ponder. “Only after he had gone did it occur to me that that wouldn’t prove it wasn’t funny.”

Archie’s comment tops the topper, indicating that the smartass dialogue is set inside an even richer verbal texture. The Wolfe books are the only novels in which Stout employed first-person narration. “It’s Archie who really carries the stories, as narrator,” Stout noted. “Whether the readers know it or not, it’s Archie they really enjoy.” 72 Why? I think because his performance calls on many tricks of yarn-spinning in the American grain. 72 Why? I think because his performance calls on many tricks of yarn-spinning in the American grain.

There’s exaggeration, as when Archie declares of Wolfe’s gift of a card case: “I might have traded it for New York City if you had thrown in a couple of good suburbs.” There’s vaudeville backchat. “I wanted to ask her what the difference was between asking her advice and wanting to see what she would say, just to see what she would say.” Homely synecdoche is recruited too. The sentence “I told the temples, ‘This is absolutely childish’” makes sense only because fifty pages earlier Archie has confided that slightly depressed temples on a young woman always appeal to him.

That Archie calls his books “reports” merely adds to the joke; nothing could be further from neutral description. Trying to tell all leads to digression.

Smith shook his head. That was one way in which he resembled Wolfe. He didn’t see any sense in using a hundred ergs when fifty would do the job. Wolfe’s average on head-shaking was around an eighth of an inch to the right and the same distance to the left, and if you had attached a meter to Smith you would have got about the same result. However, Wolfe was still more economical on physical energy. He weighed twice as much as Smith, and therefore his expenditure per pound of matter, which is the only fair way to judge, was much lower. 73 73

A report thrives on clichés, but Archie plays with them.

I didn’t want to give her the impression that I was at her beck, let alone her call.

“I am prepared,” Nat Traub announced, in the tone of a man burning bridges, “to say that I will vote for Meltettes.”

Above all, there’s the mixture of spoken language and literary calculation. Chandler could tell us that a man has a face like a collapsed lung, but Stout gives us something more conversational. “He didn’t look tough, he looked flabby, but of course that’s no sign. The toughest guy I ever ran into had cheeks that needed a brassiere.” Stout claimed to hate similes, but when he gives them, they supply a characterizing bonus. A woman laughs, then she stops. “A sort of chuckle came out of her, like the laugh’s colt trotting along behind.” The “sort of” preserves the oral dimension, but you can hear the chuckle in the verb “trotting.” You might even remember Archie’s Chillicothe childhood.

Archie’s demotic can slam the gearwork between high and low, lofty and ingenuous. In one of the most brilliant passages Stout ever wrote, Archie is sharing a dinner with Wolfe and Cramer.

If you like Anglo-Saxon, I belched. If you fancy Latin, I eructed. No matter which, I had known that Wolfe and Inspector Cramer would have to put up with it that evening, because that is always part of my reaction to sauerkraut. I don’t glory in it or go for a record, but neither do I fight it back. I want to be liked just for myself. 74 74

How to define the tone of this passage of mock defense—cast, inevitably, as a mingling of food and word choice? That last sentence is at once proud, self-deprecating, sincere, and a jab at the American conviction that one’s individuality is precious, even during a burp.

This is the relaxed performance of a tall tale. Admirers have compared Archie’s idiolect to that of Huck Finn, but I hear the shuttling among registers we find in Twain’s platform speeches and literary critiques. Writing of Fenimore Cooper, he notes:

In his little box of stage properties he kept six or eight cunning devices, tricks, artifices for his savages and woodsmen to deceive and circumvent each other with, and he was never so happy as when he was working these innocent things and seeing them go. 75 75