The Classical Hollywood Cinema Twenty-Five Years Along

David Bordwell, Janet Staiger, and Kristin Thompson

September 2010

This is a look back at a book that we wrote in the early

1980s and that was published in 1985. For more on the book, and our rationale

for posting this essay, see the

blog entry here.

Some background

The Classical Hollywood Cinema went through two major phases of development.

Kristin and David had been thinking about a project on Hollywood film style for

a while. Janet, who had for a seminar with Douglas Gomery written a paper on

early screenwriting and division of labor, joined them in the runup to her Ph.

D. comprehensive examinations in spring of 1979. That summer all three of us

went to Washington to watch films and do research.

Janet spent the rest of 1979 and the calendar year 1980

at her home in Cleveland doing research and writing. David and Kristin bounced

around more. They were in New York City, where David taught at NYU, during the

fall of 1979. After returning to Madison in the spring of 1980, they went to

Los Angeles for a long stretch of the summer (enjoying the unstinting hospitality

of Ed Branigan and Roberta Kimmel). Fall and spring 1980–1981 they were teaching

at the University of Iowa.

Janet defended her dissertation in May of 1981. During

the summer of 1981, all three of us met to read the book aloud to one another

and revise each other’s

work. We finished a 1350-page version of the manuscript and sent it to Princeton

University Press.

Joanna Hitchcock, then Film editor at Princeton, was a

strong backer of the book, but the first readers recommended rejection (and they

were readers we had picked!). Even with two more favorable readings, the project

was unlikely to get through the Press committee. Still, we’ll always be

grateful for Joanna’s

efforts on our behalf. 1 1

Phase

two: After the initial rejection, we set about looking for other publishers.

Those whom we approached, including Columbia University Press, declined, usually

on grounds of length. In response, we did cut about 100 pages, but the manuscript

was still vast. Finally, Philippa Brewster, of Routledge and Kegan Paul of London,

solicited other readers’ opinions and agreed to publish the book. RKP quickly

sold the US rights to Columbia. Both the UK and US editions came out in the spring

of 1985, some four years after we had finished our initial draft.

Some basic questions

Here is the opening of our book proposal.

What we propose is not another study of an outstanding individual,

a trend, or a genre. The Classical Hollywood Cinema analyzes the broad

and basic conditions of American cinema as a historical institution. This project

explores the common idea that Hollywood filmmaking

constitutes both an art and an industry. We examine the artistic uniqueness and

the mass-production aspects of the American studio cinema.

Moreover, we show how these two features fundamentally depend on one

another. On the one hand, this cinema displays a unique use of the film medium,

a specific style. This makes Hollywood cinema

amenable to being considered a group style, comparable to Viennese classical

music of the eighteenth century or Parisian cubist painting of the early twentieth.

On the other hand, we can see the specific business practices of the Hollywood industry

as initiating and sustaining its distinct film style. The history of Hollywood is

thus the coalescence and continuation of a film style whose supremacy was created

and maintained by a particular economic mode of film production.

More specifically, The Classical Hollywood Cinema addresses

four questions:

- How does the typical Hollywood film

use the techniques and storytelling forms of the film medium?

- When did the Hollywood style begin

to be formed and how has it changed?

- What particular production system has created and maintained the Hollywood style?

- How has technological change affected film style and industrial practice?

In the course of answering these key questions we had to nail down some concepts.

We weren’t discussing “the industry,” which includes not only

production but also distribution and exhibition. We discussed instead what we

called the mode of production, particular strategies for organizing work on a

wide scale. Similarly, we took “style” to include features of both

narrative form and cinematic technique. This is because we were discussing a “group

style.” Art historians discussing Impressionism would include not only

techniques of paint handling but typical subjects and iconography as part of

the general Impressionist style.

We proposed that Raymond Williams’ idea of an artistic

practice could tie together both style in the general sense and a mode of film

production. Hollywood was, we claimed, a particular “mode of film practice,” a

bundle of characteristic artistic and labor-based activities. Williams explained

the idea with a certain wooliness, but we saw what he was getting at:

The recognition of the relation of a collective

mode and an individual product—and these are the only categories we can initially presume—is

a recognition of related practices. That is to say, the irreducibly individual

projects that particular works are, may come in experience and analysis to show

resemblances which allow us to group them into collective modes. These are by

no means always genres. They may exist as resemblances within and across genres. 2 2

As the proposal indicates, our project had affinities with work in other arts.

Historians of art and music had long considered how an art movement’s output

was supported by patronage, the art market, and salons. This parallel with art

history made our enterprise different from the 1970s studies of classical textuality.

At the same time, by focusing on a popular and mass-produced art, we were going

somewhat beyond what most art historians would have tackled. There were also

kindred works in literary studies and musicology. 3 Perhaps

a closer kin is The Fiction Factory, Quentin James Reynolds’ 1955

study of Street & Smith dime novels and pulp magazines, or Mary Noel’s Villains

Galore, on story weeklies. A more serious academic parallel is Robert D.

Hume’s remarkable Development of English Drama in the Late Seventeenth

Century, an effort to combine a detailed analysis of all extant plays with

historical examination of the professional milieu (Oxford University Press, 1976). 3 Perhaps

a closer kin is The Fiction Factory, Quentin James Reynolds’ 1955

study of Street & Smith dime novels and pulp magazines, or Mary Noel’s Villains

Galore, on story weeklies. A more serious academic parallel is Robert D.

Hume’s remarkable Development of English Drama in the Late Seventeenth

Century, an effort to combine a detailed analysis of all extant plays with

historical examination of the professional milieu (Oxford University Press, 1976). 4 Since The

Classical Hollywood Cinema, there have been other studies in the same spirit. 4 Since The

Classical Hollywood Cinema, there have been other studies in the same spirit. 5 One

of the liveliest is Ken Emerson’s Always Magic in the Air: The Bomp

and Brilliance of the Brill Building Era (Viking, 2005), which shows how

a recording company can develop its own forms, genres, and division of labor. 5 One

of the liveliest is Ken Emerson’s Always Magic in the Air: The Bomp

and Brilliance of the Brill Building Era (Viking, 2005), which shows how

a recording company can develop its own forms, genres, and division of labor.

Our book was different from these others in being more

explicitly theoretical. That was partly because some ground-clearing was required.

Nowadays, for example, one wouldn’t need the extensive discussion of artistic

norms David launched in Chapter 1. Similarly, no film historians and few historians

of any art would have gone as far as Janet did in distinguishing different modes

of production, or specifying the hierarchy and the division of labor. But again,

these concepts were new to film studies, and so they needed spelling out to a

degree that wouldn’t

be necessary today.

We also had to carve out our area of study because as a

phenomenon the classical studio cinema isn’t perfectly parallel to those

we encounter in orthodox art history. It isn’t a period, because classically

constructed films are still being made. It isn’t a movement, at least like

others in film history, because those, such as Italian Neorealism, are far more

limited. It’s something

else, and it makes us rethink the categories we use to study other group styles.

We

cast our net wide, examining not only films but all the trade periodicals we

could find, archive documents recording studio production practices, and personal

recollections of people we interviewed, like Charles G. Clarke, Stanley Cortez,

William Hornbeck, Linwood Dunn, and Karl Struss. This made for a swarm of endnotes,

nearly every one packed with many citations.

And we did it all on note cards and typewriters.

David Bordwell

It’s important to realize what The Classical Hollywood Cinema is

not and never tried to be. Perhaps the most common strain of criticism was that

it didn’t take into account other things.

Why did we not do a full-blown comparative study, situating Hollywood in

relation to other national cinema traditions? There is a serious

methodological point here. How, after all, can you be sure that the features

of technique or narrative that you’re picking out distinguish Hollywood?

Perhaps we find the same features in French or Brazilian films. The reply is

that we did rely on our intuitive experience with other traditions to come up

with some broad contrasts with other modes of filmmaking (e.g., Soviet montage

cinema, contemporary art cinema). Moreover, especially in the pre-video era,

a systematic and fairly comprehensive cross-national study of this sort wasn’t

practical. Kristin and I have gone on to try to trace alternative styles, 6 but

film studies is still very far from a complete comparative study of aesthetic

traditions in international popular cinema. That is largely because most scholars

do not pursue analysis of form and style. 6 but

film studies is still very far from a complete comparative study of aesthetic

traditions in international popular cinema. That is largely because most scholars

do not pursue analysis of form and style. 7 7

Why didn’t we situate Hollywood in

relation to American society as a whole? The jump to socio-cultural

explanation is always tempting, and nearly every historian before us had succumbed.

Part of our point was to show that a great many questions can be answered satisfactorily

by examining what Sartre called mediations—the processes and social

formations that intervene between an art work and the broader society.

In our case, the mediations were the institutions in and around film production,

as well as the discourses those institutions generated.

Why didn’t we discuss reception? We anticipated

this query and in our preface we wrote:

If we have taken the realms of style and production as primary, it is

not because we consider the concrete conditions of reception unimportant. Certainly

conditions of consumption form a part of any mode of film practice. An adequate

history of the reception of the classical Hollywood film

would have to examine the changing theater situation, the history of publicity,

and the role of social class, aesthetic tradition, and ideology in constituting

the audience. This history, as yet unwritten, would require another book, probably

as long as this one is.

Unlike form and style, reception has occupied the attention of many researchers

in the last few decades. Today I would suggest that we need some hypotheses about

how concrete conditions of reception could influence the look and sound of the

films. Theatre layout, screen size, and schedules of the showing day could well

be important factors. 8 8

Why did we not spend more time on individual

filmmakers? From

one angle, this objection entails a different set of questions than we chose

to focus on. For some decades before CHC, most serious works of film

studies cinema concentrated on auteurs or genres. In contrast, we aimed to bring

out the norms or implicit standards that Hollywood filmmakers as a community

practiced. We did try to suggest that these norms formed a set of options, a

paradigm from which a filmmaker might pick. One implication of our project was

that we might be able to characterize a filmmaker’s originality more exactly

by noting what choices were favored in the body of work. It’s nonetheless

fair to say that we emphasized the menu over the meal. Accordingly, readers more

interested in emphasizing the originality of films or directors would find our

work at best preliminary.

A more complicated methodological question comes up

here. We decided to select two batches of films. One consisted of a hundred titles

generated by using a random-number array; this we called our “Unbiased

Sample.” (It wasn’t

strictly random, since not every film we initially listed survived, and so didn’t

have an equal chance of being picked.) The second batch consisted of another

two hundred films we picked because of renown, acknowledgment in the trade literature,

and other factors. This we called the “Extended Sample.” Through

these two bodies of film we deliberately moved from auteur aspects of the films

we studied.

This isn’t the only way, or even the most common

way, to study a group style. Researchers often study a group style by picking

influential works and valued creators. Charles Rosen’s The Classical

Style,

for instance, concentrates on Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven for the simple reason

that they created the style and were from the start its most accomplished and

influential exponents.

But Hollywood film style did not originate or sustain

itself in this fashion. There is no single creator or cadre of creators to whom

one can attribute the style. Griffith is often considered the central innovator,

but his films are in many respects untypical of what would become the classical

cinema. When Kristin and I asked Dore Schary about what films influenced studio

filmmakers of the 1930s, he said there was no single film, but everybody who

made films wanted some of the lively energy of the play version of The Front

Page. That’s

an interesting point, but it doesn’t identify the sort of breakthrough

works one finds in schools of literature or painting.

Twenty-five years later, and after studying a lot more movies from the era, I

still think that we are dealing with a collective invention. It’s an academic

style without much of a canon. In this respect (and to revise the formulation

in our proposal), classical filmmaking isn’t a well-punctuated group style

like Viennese classical music or Impressionist painting. It develops more in

the manner that visual perspective, or, to take a musical analogy, Western tonality

did. Certainly there were powerful filmmakers who took the received style in

fresh directions, and sometimes those creators influenced others. But in its

totality, the classical Hollywood style is an instance of an “art history

without names.” It is the result of many routine iterations, accompanied

by both striking innovations and minor tweaks. It was maintained for decades

by a host of creators both major and minor, famous and anonymous. Gathering data

from films en masse seems to suit a collective trend.

What’s in a name?

Some people objected to using the word “classical” to describe the

studio style. Did it make us seem conservative theorists? In a word, no. The

word was already circulating in French and English-language film talk. On the

first page of the book we pointed out that it dates back at least to the 1920s.

Did it commit us to a “neoclassical” aesthetic, believing in adherence

to rules and academic canons? In the same word, no. We used “classical” as

shorthand description, and it carries no deep commitment to a worldview or an

aesthetic. All of three of us have written about “unclassical” cinemas.

The worry about terminology recalls a point made by Karl Popper.

In science, we take care that the

statements we make should never depend upon the meaning of our terms. Even where

the terms are defined, we never try to derive any information from the definition,

or to base any argument upon it. This is why our terms make so little trouble.

We do not overburden them. We try to attach to them as little weight as possible….

This is how we avoid quarreling about terms. 9 9

By contrast, literary academics often argue about terminology, insisting that

the choice of a single word reveals deep things about an author’s conceptual

commitments and biases. Perhaps this is one reason the literary humanities make

so little progress in producing reliable knowledge. In our book we used the term “classical” because

it was current. After hearing about our project, a colleague gave an encouraging

response: “Maybe after you do this we’ll finally know what we’re

doing when we talk about a classical film.” And early on in the book (CHC,

3–4) we say that the word isn’t the worst that could be found. But very

little hangs upon it. “Classical” in our title could easily be replaced

by another word, say “standard” or “orthodox” or “canonical.” The

substance of our evidence and arguments would not be changed.

It is that substance that may have proven most fruitful

in CHC. We made

claims about a wide variety of historical processes, and those claims impelled

later scholars to test them—sometimes to contest them, sometimes to refine

them, sometimes to find further support for them. The book seems to have helped

scholars of a certain temperament find a fit between the film industry and film

artistry. 10 10

Some

have speculated that the book pluralized the field, turning research away from

abstract theory (or Theory) toward more concrete and empirical research programs.

This is partly true, but I think CHC had little effect on

the two primary tendencies in film studies. Despite many writers’ claim

to think historically, the dominant method in the field remains hermeneutics

driven by Grand Theory. Once the Theory was derived from Foucault or Lacan, now

it comes from Zizek or Deleuze, but the conceptual and rhetorical moves are the

same. At the other pole, there stand those who believe that what’s important

about film as an art can’t be explored by quantitative methods, models

of social organization, or specification of stylistic parameters. For such academics,

the intuitions of the sensitive critic, perhaps steered by an approved theory,

will always be preferable to inductive inference based on historical research.

Again, this is largely a matter of the different research questions that people

are inclined to ask.

As for things I would change: There’s scarcely a

page of my chapters in CHC that

I wouldn’t want to fiddle with—to clarify, expand, nuance, or prune.

I think, for example, I came up with a better way to explain my idea of narration

in the book devoted to that subject. The invocation of mental schemas in the

Hollywood book seems to me cumbersome. My discussion of sound, and music in particular,

is sketchy at best and in fact contains one howler: Not “Ernest Newman” but

of course Alfred Newman (CHC, 33). Fortunately many scholars have since

then dug into Hollywood recording and scoring practices with far more precision,

largely supplanting my account. 11 11

In pursuit of poetics

What did I learn from CHC? More or less a new way to think about film.

Our effort to articulate the premises and vagaries of Hollywood filmmaking offered

me my first opportunity to practice a historical poetics. By forcing me to spell

out the principles and practices of a tradition, to trace the conditions that

foster innovation, and to consider the tradition’s ties to proximate social

institutions, writing the book became more than a research project: It promised

a research program. You could find an intriguing film, and then shuttle to and

fro between that and other films that manifested similar strategies of storytelling

or style. In the process you could expose some principles behind the film’s

design, all the while still finding areas of difference, even uniqueness. Once

you had located some principles, that discovery made other films—films

you hadn’t noticed before—more interesting. A film’s distinctiveness

could in large part be said to lie in its transformations of schemas available

to both filmmakers and film viewers. And the researcher could bring those patterns

out, and seek causes within the filmmaking community for this whole dynamic.

Once

I realized that I was pursuing a poetics, I started to understand why some scholars

resisted my conclusions. For many, a film writer’s central task

is to interpret and evaluate individual works—as art, as politics, as expression

of social identity or modern culture. Judicious criticism of one stripe or another

is taken as the heart of film studies. So anything that smacks of generalization

does violence to the integrity of the film at hand. For other scholars, tracing

general principles of form and style within a tradition isn’t theoretical

enough if the conclusions don’t lead to generalizations about culture as

a whole. Middle-level theorizing isn’t considered interesting. In addition,

an emphasis on aesthetics is suspect. At once over-theorized and under-Theorized,

a poetics of cinema still lies outside many academics’ agendas.

I think

that film-critical appraisal and general theorizing are intrinsically valuable,

but when you undertake particular research projects, they aren’t

always needed. Many inquiries need something in between, as I’ve argued

at various points in my work. More to the issue here, since 1985 I’ve tackled

several questions that develop ideas and information I encountered in writing CHC.

For example, many writers seem to have taken our period’s 1960 cutoff point

as an assertion that after that point Hollywood developed a “post-classical” style.

I’m not of that persuasion, for reasons I explain in The Way Hollywood Tells

It. But in arguing further for the persistence of classical principles in

the 1980s and 1990s, I found new areas of innovation within the system, particularly

with respect to narrative structure. I keep learning that ingenious filmmakers

can renew this tradition almost indefinitely.

Similarly, some readers have objected

that my conception of classical storytelling is too tidy, that Hollywood films

are more disjointed than I allow. Causality is less important than “spectacle,” many

say. I’ve not been

convinced by the arguments I’ve seen in the literature, and I try to rebut

them elsewhere

on this site and in The Way Hollywood Tells It. More broadly, my

thoughts on plot unity emerge in Planet Hong Kong,

which is another attempt to characterize a popular mode of filmmaking. There

I suggest what a tradition of genuinely episodic storytelling looks like, and

I try to characterize the other principles that emerge to shape these movies.

In that book as well I try to connect style with mode of production (which led

the Variety reviewer to characterize me as a Marxist).

Likewise, my book Narration in the Fiction Film, written while we were

waiting for a publisher to risk printing CHC, recasts some of the CHC’s

theoretical framework pertaining to narration and situates classical narration

in a wider field of options. Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema is an authorial

study that tries to capture Ozu’s transformation of norms he inherited

from both Hollywood and Japanese film traditions. My books on the history of

style and the traditions of cinematic staging are further studies in norms and

their creative recasting. Many of my online essays and blog entries bear on the

same issues. My study of Eisenstein is at once an auteur analysis and an account

of a director who himself explicitly aimed to create a poetics of cinema. Most

recently, the first essay in Poetics of Cinema is my attempt to sum

up what I’m aiming to accomplish in the study of film. In sum, if anyone

is tempted to take what I wrote in CHC as definitive, or as my final

thoughts, I urge them to turn to my later work. I’ve learned a few things

since 1985.

Perhaps the most valuable thing I’ve learned is

that analyzing craft is endlessly interesting. By studying Hollywood with my

two collaborators I was constantly reminded that art-making is a human activity,

guided by will and skill, working on materials inherited from others. And this

activity takes place within a community of artisans, who are sharing information

but also competing to do something fresh. The line between craft and artistry

in its more exalted sense is a hazy one, and I don’t claim to be able to

define it. But I’ve

worried little about drawing that line. Instead, I’ve surrendered to the

pleasure of finding things out about how filmmakers do what they do. I want to

know their secrets, even the ones they don’t know they know.

Once after

a day spent studying a sequence in a swordplay film, I told a friend that I’d

figured out how King Hu got the effect he wanted. She said, “Well,

I guess that’s all right, as long as you don’t tell anyone.” Fat

chance.

Janet Staiger

I am personally extremely proud to have been associated

with David and Kristin’s

expansion of some art historical theories into moving images. Perhaps one

reason that I worked well with them was that Herbert Eagle had introduced me

to the Russian Formalists before I arrived at the University of Wisconsin. I

find symptomatic criticism (finding subtexts of race, sex, sexual, and class

ideologies within films) a valuable critical project because I believe that many

people see such ideologies while watching films. However, I also believe

that Neoformalism has the greatest critical scope for describing and analyzing

works of art.

When I came onto the project in the late 1970s, also influential

for me were Marxism and the ideological critique of romantic authorship since

these theories assumed a historical materialist base. This philosophical

position was much more credible to explain history and historical change. It

also fit with my biography as a working-class daughter who was a first-generation

college student. It

matched my political progressivism. Turning to an eclectic group of Marxist

theorists—Harry Braverman, Raymond Williams, Jean-Louis Comolli, John Ellis,

Louis Althusser, and other analyses of modes of production—I looked for

(and found) valuable explanations about how and why labor divided and constructed

systems of bureaucracy and work patterns to insure both the standardization and

differentiation of an entertainment product. One of the points that I stressed

was that “what was occurring was not a result of a Zeitgeist or

immaterial forces. The sites of the distribution of these practices were

material: labor, professional, and trade associations, advertising materials,

handbooks, film reviews” (CHC, 89). Although I had not been

reading contemporaneous structural-functionalist production of culture literature

by Howard Becker, Paul DiMaggio, Paul Hirsch, Richard A. Peterson, and others,

similar general issues permeated both sets of literature even if the theoretical

explanations differed.

It is now exciting to see how many scholars are

beginning to do production of culture work on contemporary Hollywood—both

the film and television sectors, for instance, John Thornton Caldwell’s Production

Culture and

Vicki Mayer, Miranda J. Banks, and Caldwell’s Production Studies: Cultural

Studies of Media Industries. Differences do exist between these volumes

and the project of CHC. I was focused on the past rather

than contemporary practices. While I used interviews published in trade

papers, I did not engage in ethnographic research: most of my subjects

were elderly or deceased. Moreover, I was trying to capture the discursive

establishment of the production practices ca. 1915, not 1980, and we know how

suspect individual memories can be for oral history. The current production

of culture work indicates that little has changed in the Hollywood mode of production

and its discourses in the past ninety years. The talk amongst workers and

their labor practices continue to be crucial in understanding how films and television

programs are financed and created. Variations also need to be studied,

of course, but a strong sense of what remains the same and what differs offers

a growth of knowledge and a historical account. Trying to tie together

work of the 1910s and 1920s with the present excitement about these questions

is an important and worthwhile research project.

Additionally, a whole field of scholarly study of screenwriting

practices has developed over the past thirty years. Starting from CHC’s

premise that the script functioned in Hollywood not only as a guide for shooting

the film but as the blueprint for the entire efficient planning of the film,

scholars are now exploring the historical transitions and variations of this

part of the work process.

Of course, questions have been raised about parts of the industrial and institutional

analysis. One criticism of the mode of production sections was their failure

to discuss the broader industry. When I read that, I actually laughed,

partially in agreement. In my first draft of my dissertation, I had an

extensive description and analysis of the industry, but wise counsel was that

I was writing two dissertations. I agreed, and we eliminated the

industrial details from the dissertation and the book, trying instead to focus

on pertinent effects of the broader industry on its mode of production and leaving

to others further detailing of industry structure, conduct, and performance. After

all, we had over 1200 typescript pages, and not everything could be said to create

a somewhat manageable book. So that, for me, has always been one

of those ironies about the project which I might have explained in the foreword.

Two criticisms about the CHC textual argument

are that it does not seem to account for spectacle or for emotional trajectories

in narratives. I have mixed beliefs about the validity of these complaints. As

with our divided labor in CHC, I will tackle the question from the mode

of production angle.

Regarding spectacle, I think that CHC does

acknowledge its function within the Hollywood mode of production. However, little

time was spent emphasizing this or the presentation was lost to our readers.

In my sections, I discuss spectacle as a major selling point (CHC, 96–102),

and I even provide a theory of the necessity of product differentiation that

includes spectacle (CHC, 108–12). In fact, the articulation

of this argument—standardization

vs. product differentiation as the economic motor of Hollywood production—is

now so accepted in the field that discussions in CHC and other texts 12 are

no longer even cited. At any rate, the production sections in CHC did

not dwell on excessive discussion about spectacle per se but did acknowledge

spectacle as one factor that is a major component within the Hollywood system—both

in narrative and economic terms. 12 are

no longer even cited. At any rate, the production sections in CHC did

not dwell on excessive discussion about spectacle per se but did acknowledge

spectacle as one factor that is a major component within the Hollywood system—both

in narrative and economic terms.

The complaint about not discussing emotional trajectories (particularly in melodrama)

in narratives has a bit more validity; I have wished that we had paid more attention

to the industrial discourse about emotional experiences for spectators. In

a separate discussion about variable approaches to reception of films, I discussed

my concern that neoformalism as an enacted critical practice might place too

much weight on some actions by spectators (seeking causal motivations, organizing

chronology). 13 Yet,

this is not inherent within its premises. How formal systems of texts solicit

other aspects of watching films (alliance with characters, tears and laughter)

could certainly be considered. The question is: what is possible in a

historical analysis and in a critical method? 13 Yet,

this is not inherent within its premises. How formal systems of texts solicit

other aspects of watching films (alliance with characters, tears and laughter)

could certainly be considered. The question is: what is possible in a

historical analysis and in a critical method?

I believe that CHC’s analysis of the mode of production and style could be

used to describe emotional trajectories by considering other aspects of the formal

arrangement of devices (although as with motivations and causality, the spectator

would need to be hypothetical). Indeed, one of the outcomes of the

book has been the application of the critical method to further film practices

and the attempt to work on emotional trajectories as well as the composition

of plot and story (see the work of Murray Smith, Carl Plantinga, and Greg Smith). 14 From

the production perspective, the CHC does open the door to looking at

the industry’s discursive preferences about creating a story that produces

emotional affects, which we certainly did discuss. Particularly in Kristin’s

sections about scriptwriting, matters such as “punch” and clarity

of action for comedic effects are product expectations to insure audience emotional

engagement. 14 From

the production perspective, the CHC does open the door to looking at

the industry’s discursive preferences about creating a story that produces

emotional affects, which we certainly did discuss. Particularly in Kristin’s

sections about scriptwriting, matters such as “punch” and clarity

of action for comedic effects are product expectations to insure audience emotional

engagement.

In relation to these criticisms of gaps in our discussion,

I also wish we had spent a bit of time on a mid-level set of norms commonly referred

to as genre. 15 I

discussed the production reasons for cycles (CHC, 110–12) that include

genres as well as stylistic practices. David deals with generic motivation

as one of the four major constructive principles for classical construction,

and he analyzed film noir as a group of films (CHC, 74–77).

A glance through our index indicates that we have sporadic comments on these

groupings and the sorts of affects they solicit, but a section on these clusters

of texts as perceivable groups within the broader scale norms that we were trying

to describe would have been helpful to articulate our analysis of how the mode

of production encourages the use of genre (its standards ensure both efficient

and effective production) and how discursive systems articulate what constitutes

good (and not-so-good) storytelling practices. 15 I

discussed the production reasons for cycles (CHC, 110–12) that include

genres as well as stylistic practices. David deals with generic motivation

as one of the four major constructive principles for classical construction,

and he analyzed film noir as a group of films (CHC, 74–77).

A glance through our index indicates that we have sporadic comments on these

groupings and the sorts of affects they solicit, but a section on these clusters

of texts as perceivable groups within the broader scale norms that we were trying

to describe would have been helpful to articulate our analysis of how the mode

of production encourages the use of genre (its standards ensure both efficient

and effective production) and how discursive systems articulate what constitutes

good (and not-so-good) storytelling practices.

Twenty-five years later?

My research has continued from the bases of CHC. It has taken

two directions. One is a concern to explain the detailed workings mode

of production. As our proposal for the book put it, our point was to appreciate

how a group of people operated within a set of industrial conditions. Still,

in every group, some actions are more fruitful to the system than others. So

a further question is to explain the behavior of an individual within the institution

and the reactions of the institution to that person’s behavior. For

instance, Thomas Ince’s method of organizing efficient and, hence, economical

production through the tool of the continuity script (and associated paperwork)

seems to have created a standard. I stressed that the term “standard” has

two meanings: “one is regularity or uniformity…. [the other

is] a criterion, norm, degree or level of excellence” (CHC, 96). Ince’s

system was a standard that spread throughout the industry and within a few years

was common work practice.

We might now want to call Ince a “genius of the

system,” but, like

André Bazin, I would prefer to emphasize the “system” rather

than “genius.” 16 Still

it is important to recognize the value of Ince’s appropriation of common

business practices and application to filmmaking. We dedicated our

book to the workers whose labor seemed to typify the excellence of the system.

We wrote: “Dedicated to Ralph Bellamy, Margaret Booth, Anita Loos,

Arthur C. Miller, and their many co-workers in the Hollywood cinema.” 16 Still

it is important to recognize the value of Ince’s appropriation of common

business practices and application to filmmaking. We dedicated our

book to the workers whose labor seemed to typify the excellence of the system.

We wrote: “Dedicated to Ralph Bellamy, Margaret Booth, Anita Loos,

Arthur C. Miller, and their many co-workers in the Hollywood cinema.”

The value of worker innovations is material, and CHC tried to show how

the contradictory nature of capitalism rewarded both adherence to and variation

from the norms (both standardization and differentiation). That

observation works not only for the system but also for the individual operating

within Hollywood. Both economic and stylistic analysis points to

a bounded set of options that have flexibility to change. Such an

observation is not one solely available to scholars. People working within

the industry may witness it operating. I stressed in my evaluation

of the Hollywood mode of production that an ideological attitude about authorship

had permeated the industry by the 1930s (CHC, 336). It is

scarcely a grand observation to note that discourses resembling early forms of

auteurism appear in industry and educational venues; D. W. Griffith even put

out ads in trade papers in the early teens claiming he invented various stylistic

practices (see http://www.davidbordwell.net/blog/?p=1174).

Thus, promoting one’s self has been, throughout the history of Hollywood,

part of labor practices. 17 Analyzing

authorship as a determined and historical agency continues as one of my on-going

research agendas. 17 Analyzing

authorship as a determined and historical agency continues as one of my on-going

research agendas.

The other direction that I have taken is trying to develop a historical materialist

account of reception. One of the most obvious divergences in our research

paths since CHC has been our view of how to pursue the question of consumption

of films. First of all, I would point out that despite how in sync theoretically

we were in 1980, differences still existed. For one that I remember in

particular, I wanted to use the term “signifying practices,” a concept

which obviously is not Neoformalist. When we divided our labor and indicated

specific authorship to various portions of CHC, I recall our doing this

for at least a couple reasons. In part, I did not yet have my doctoral

degree, and David was a young associate professor; dividing labor would allow

readers to assess each author’s contributions—an important factor

in academic evaluation. Additionally, this decision ultimately allowed

us to resolve disputes. Despite our attempts to convert one another to

our point of view, if we failed, we would say, “Well, it’s your section.”

This retrospective is not the place to hash out differences of opinion about

research in reception. In my view, David’s trajectory has been to

consider how textual systems solicit and cue hypothetical spectators to engage

with a film. In many instances, hypothetical spectators are very

much like historically constituted spectators. My trajectory has been to

try to develop historical methods to investigate actual instances of reception

in order to work towards theorizing the real effects of cinema and other media

within social and cultural circumstances. I see a place for both sorts

of questions, but I do see significant differences in what they want to explain.

So,

rather than develop those differences, I choose to celebrate what we achieved

with CHC and what a pleasure it has been to have had that early professional

collaboration and our ongoing friendship.

Kristin Thompson

Today there are annual festivals of silent cinema, award-winning DVD boxes

of restored silent films, and even the weekly “Sunday Silents” series

on Turner Classic Movies. In 1978, unless one did research in an archive or could

attend public screenings at places like the Museum of Modern Art and George Eastman

House’s Dryden Theater, silent films consisted mainly of 16mm prints, often

transferred from mediocre copies, of classics by Griffith, Keaton, Chaplin, and

the best-known of the foreign directors.

We conceived The Classical Hollywood Cinema in

1978, during a period when the study of the silent era was undergoing a seismic

shift.

Museums provided some of the earliest alternatives to the

standard accounts of Hollywood’s history, as when Richard Koszarski programmed

films by then little-known directors like Maurice Tourneur, Benjamin Christensen,

and Reginald Barker. 18 18

As

we were formulating our project, the Fédération Internationale

des Archives du Film (FIAF) held its landmark 1978 conference, termed the “Brighton

Project.” That event attempted to program all the surviving films from

the 1900–1906 era. Those not lucky enough to have attended first learned of it

in late 1979 through Eileen Bowser’s “The Brighton Project: An Introduction.” The

two volumes of proceedings, one a hugely helpful filmography, were not published

until 1982. 19 Another

important publication that came out of the conference was André Gaudreault’s “Temporalité et

narrative: Le cinéma des premiers temps” (1980). 19 Another

important publication that came out of the conference was André Gaudreault’s “Temporalité et

narrative: Le cinéma des premiers temps” (1980). 20 20

In those days, Robert C. Allen’s dissertation Vaudeville and Film 1895–1915:

A Study in Media Interaction (finished 1977, published 1980) 21 was

our primary source for the fledgling cinema’s relationship to vaudeville,

and Nicholas Vardac’s Stage to Screen our source for its relationship

to live theater. 21 was

our primary source for the fledgling cinema’s relationship to vaudeville,

and Nicholas Vardac’s Stage to Screen our source for its relationship

to live theater. 22 22

Charles

Musser, who would contribute to our knowledge of early exhibition, Edwin S. Porter,

and the nickelodeon era, was just beginning to publish his work in article form.

Our access to his discoveries was “The Nickelodeon Begins:

Establishing the Foundations for Hollywood’s Mode of Representation” (1983). 23 In

fact, we were virtually finished with revising the book to shorten it when Musser’s

piece appeared, and we were able to refer to it only in Chapter 14, footnote

9 (p. 439). 23 In

fact, we were virtually finished with revising the book to shorten it when Musser’s

piece appeared, and we were able to refer to it only in Chapter 14, footnote

9 (p. 439).

Barry Salt’s pioneering work on the history of film

technique and style had begun before we conceived our book. His articles “Film

Form 1900–06” (1978)

and especially “The Early Development of Film Form” (1976), were

useful guides as we pursued our research. His Film Style & Technology:

History & Analysis did not appear until after we had finished our book. 24 I

was encouraged by the fact that he pinpointed the year 1917 as the point when

the classical stylistic system became dominant practice in Hollywood; my own

work indicated the same thing. 24 I

was encouraged by the fact that he pinpointed the year 1917 as the point when

the classical stylistic system became dominant practice in Hollywood; my own

work indicated the same thing.

A lesson from 1915

In the intervening years, the field of silent-film studies has burgeoned, and

it now seems astonishing to look back thirty years to the situation when we launched

our project. Its twenty-fifth anniversary inevitably leads me to wonder what

I would do differently now.

Recently I had occasion to seek out my folder of photocopied articles on continuity.

One brief piece by an early expert on the subject suggested one aspect of classical

editing that I had discerned at the time but not dealt with sufficiently.

The

expert was Epes Winthrop Sargent, whom we often had occasion to quote in CHC. He

was an authority on screenplay-writing, contributing a regular column, “The

Photoplaywright,” to The Moving Picture World and publishing one

of the best how-to books of the day, The Technique of the Photoplay (three

editions, 1912, 1913, and 1916).

In one of his columns from early 1915, Sargent dealt with

the subject of “Cutting

Back.” 25 In

one usage of the time, “cut-back” seems to have referred to cross-cutting.

But sometimes the term designated a cutting pattern in which shots taken from

the same basic framing are inserted at intervals across a scene. That yields

at least two areas of space that are intercut. But are the two areas close to

each other or far apart? Would shot/reverse shot editing between two people conversing

count as a series of “cut-backs”? I’m not sure, but from the

example I’m about to give, shot/reverse shot with the characters at a greater

distance, in this case about forty feet, does seem to constitute an instance

of cutting back. 25 In

one usage of the time, “cut-back” seems to have referred to cross-cutting.

But sometimes the term designated a cutting pattern in which shots taken from

the same basic framing are inserted at intervals across a scene. That yields

at least two areas of space that are intercut. But are the two areas close to

each other or far apart? Would shot/reverse shot editing between two people conversing

count as a series of “cut-backs”? I’m not sure, but from the

example I’m about to give, shot/reverse shot with the characters at a greater

distance, in this case about forty feet, does seem to constitute an instance

of cutting back.

In illustrating how aspiring screenwriters might understand

the cut-back, Sargent came up with a hypothetical scene, one that he realized

was clichéd and

rather silly, but that does make his point.

I was struck by one aspect of this

little scene as he broke it down into numbered shots (or “scenes,” as

they were called at the time). In 1915, two years before the continuity editing

system really gelled and became nearly universal practice in American films,

almost every shot description contained a suggestion of how clear spatial relations

could be sustained across a sequence. That is, most shots contained either a

description about where the character was looking (eyeline

matches and shot/reverse shots) or moving in relation to the frame-line.

Below I’ve quoted the entire example, which is obviously aimed at real

beginners. In the numbered shot list, I’ve indicated phrases describing

eyelines in italics and those describing figure movement in bold.

Cutting back seems to be one of the chief difficulties of the beginner

and yet cutting back is quite simple once the mechanism of the idea is understood.

Suppose

that Bill has fallen down the cliff and Lottie wants to drag him up with a rope.

Of course Lottie could not do this in real life without the aid of a pulley,

but we’ll forget that side of it for a moment. The novice

would write the scene something like this:

19—Cliff—Bill at bottom

hurt—Lottie looking over

the top—calls to him to be patient—gets lariat from Bill’s

saddle—lowers down—Bill puts under arms—she pulls him part

way up—tired—stops to spit on her hands—Bill drops to bottom

again—dies.

We’ll suppose that this is a nice, easy

little cliff with a drop of only about forty feet. Played as one scene, the camera

would have to be so far away from the cliff in order to get in both top and bottom

that the players would be about two inches high on a big picture. The expression

could not be seen and practically none of the details of the action. But by cutting

back we can get, each time, the full detail and at the same time get the suggestion

of height. Look at this:

19—Bottom of cliff. Bill on ground—apparently

badly hurt.

20—Top of cliff—Lottie cautiously approaches the edge—looks

over.

21—Bottom of cliff—Bill hears Lottie—looks up—calls.

22—Top of cliff—Lottie rises—in despair—undecided—has

an idea, runs out of scene.

23—Cliff near No. 20—Horses (Bill’s and Lottie’s)

picketed—Lottie runs in—snatches lariat from the pommel of Bill’s

saddle—runs out—

24—Top of cliff—Lottie runs in with lariat—drops end

over cliff.

25—Bottom of cliff—lariat comes into picture from above.

Bill seizes—starts to put under arms.

26—Top of cliff—close-up of Lottie watching Bill—her

face shows intense anxiety.

27—Bottom of cliff—Bill now has lariat under arms—gives

signal—rises slowly out of scene.

28—Top of cliff—Lottie braced-pulling on rope—strain

almost too much for her—stops—breathing heavily—afraid she

cannot hold on.

29—Flash [brief shot] of Bill, suspended by rope, hanging in the

air—shoot out to get clear sky, or suggestion of great height.

30—Top of cliff—Lottie rallies—fresh determination—lets

go rope to spit on her hands—rope whips out of scene—Lottie realizes.

31—Bottom of cliff—Dummy dropped into scene—cut.

32—Top of cliff—Lottie looks down—calls—

33—Bottom of cliff—Bill lying there—dead.

34—Top of cliff—Lottie realizes it is all over—starts

for home.

This is sixteen scenes instead of one, but the actions run very little

longer, and the dramatic tensity [sic] is greatly increased.

The simple sequence illustrates the “cut-back” through

an editing pattern that cuts back to the top of the cliff, then back to the bottom,

and so on.

Apart from the beginning and end of this brief action,

only one pair of shots lacks an eyeline or figure-movement cue. Shots 28 and

29 are privileged because they set up the reason for the catastrophe. We must

concentrate on Lottie’s

acting to sense her growing weariness and a brief shot of Bill to remind us of

what is at stake if she fails.

Indeed, Sargent emphasizes that the sequence needs

to be broken down into a series of closer shots for precisely this reason: we

need to see the expressions and “the

details of the action.”

This is basically the argument made in Chapter 16

of CHC: that continuity

editing gradually replaced single-shot scenes because the filmmakers could provide

better clarity for the viewer. Individual character expressions and details could

be emphasized via closer views exactly at the moments when they were most significant

to our understanding of the plot.

Reading over Sargent’s example, I realized

that there is another important facet to the flow of action across shots which

I did not discuss sufficiently in CHC. The closer views also link our

attention to that of the characters. Because characters are the main forces driving

the story causality, we are concerned to see what they see and understand how

they react to it. I did devote one paragraph to this notion, in the conclusion

of the section on the development of analytical editing:

The classical

cinema’s dependence upon POV shots, eyeline matches,

and SRS [shot/reverse shot] patterns reflects

its general orientation toward character psychology. As Part One stressed, most

classical narration arises from within the story itself, often by binding our

knowledge to shifts in the characters’ attention: we notice or concentrate

on elements to which the characters’ glances direct us. In the construction

of contiguous spaces, POV, the eyeline match, and SRS do

not work as isolated devices; rather, they operate together within the larger

systems of logic, time, and space, guaranteeing that psychological motivation

will govern even the mechanics of joining one shot to another. As a result, the

system of logic remains dominant. (CHC, 210)

All true, and yet I now think I should have spent more

time considering this notion of attention, rather than focusing so thoroughly

upon the devices for achieving continuity and hence clarity.

A few years later I discussed our close concern with character

attention and reaction in my essay, “Closure within a Dream? Point of View

in Laura.” 26 There

I adopted Boris Uspensky’s term “spatial attachment” to describe

situations in which shots do not represent a character’s visual point of

view but do systematically keep us close enough to consistently concentrate on

his or her knowledge and emotions. I describe the techniques of the continuity

system as functioning to create that concentration. (See pages 174 to 175.) This

focus on characters’ shifting vision and thought is referred to in common

parlance as character identification. 26 There

I adopted Boris Uspensky’s term “spatial attachment” to describe

situations in which shots do not represent a character’s visual point of

view but do systematically keep us close enough to consistently concentrate on

his or her knowledge and emotions. I describe the techniques of the continuity

system as functioning to create that concentration. (See pages 174 to 175.) This

focus on characters’ shifting vision and thought is referred to in common

parlance as character identification.

I now think that I should have discussed

the increasing focus on character attention as somewhat parallel to the concurrent

shift from expository to dialogue titles. In discussing intertitles in CHC,

I emphasized the move during the 1910s from a dependence primarily on expository

titles to one on dialogue titles (pp. 183–89). One purpose of this shift was

to make the narration of the action less overt, making the story information

seem to come from the characters rather than from a commenting, omniscient non-diegetic

source.

Expository intertitles are generally more noticeably overt

as narration than are cut-ins from a long shot of a room to an item on a table.

If no one within the scene is looking at the item, the cut’s motivation is less clear:

An overt narrational force wants us to notice it. But at least the closer shot

is within the diegetic space, while an intertitle is not. If a character notices

the item and a cut-in to it follows, the narrational manipulation remains within

the story space and fits into the general flow of character-based information.

Thus dialogue titles and character glances both make the narration seem to come

from the people in the story.

Where’s the four-part structure?

On the whole, though, I have found that twenty-five years of viewing hundreds

of additional American silent films has largely confirmed the account of the

historical development of the continuity editing system as originally presented

in 1985.

One last point. Some readers might expect CHC to

mention ideas that emerged in my later work on large-scale narrative structure.

In Storytelling

in the New Hollywood (1999), I propose that traditional classical plots

consist of four major, roughly temporally equivalent large-scale parts; films

with such plots are considerably more common than those with the “three-act” structure

popularized by Syd Field in his Screenplay (1979).

Ideally, yes: Had

I recognized the kind of form that I analyzed in the later book, we should have

at least briefly discussed the four-part structure somewhere in CHC. But

that was a concept that wasn’t a major part

of Hollywood’s own conception of the stylistic and formal guidelines that

we call “classical.” Practitioners did not describe their stories

in such terms. For techniques like three-point lighting and consistent screen

direction, we could point to examples, make generalizations from numerous cases,

and quote from contemporary sources. That would not have been true for the four-part

structure.

The four-part structure is an analytical observation more

general and conceptual than the other techniques we described in the book. It

is something that would need to be proven to be part of the system by examining

many films for their common underlying patterns.

As a concept, the idea of large-scale

parts, or “acts,” divided

by the film’s most important turning points didn’t come to be common

currency until 1979. Even then, it was an idea circulated primarily among aspiring

scriptwriters. 27 27

I started studying recent classical narrative films in the late 1980s, first

presenting a series of analyses of individual films to a group of film critics

in Beijing in 1988. Subsequently I wrote essays on additional films and turned

them into a book, Storytelling in the New Hollywood.

Among other things, the book was intended to show that,

contrary to what many critics and film historians were saying, the classical

narrative is not a thing of the past. We have not entered into a post-classical

era dominated by films sacrificing traditional narrative techniques like goal

orientation and dialogue hooks in favor of sheer spectacle.

To demonstrate that the four-part structure was part of what stretched back into

the earlier studio era, I included an appendix where I timed ten films from each

decade reaching back to the 1910s, when feature filmmaking was standardized.

(This was not an unbiased sample, as in The Classical Hollywood Cinema;

these films were chosen because they are considered models of Hollywood scriptwriting

practice.) Although I occasionally found three-act films, four large-scale parts

were far more common, even in short features from the 1910s.

Thus the four-part

structure had to be studied in reverse, from modern films (where I had first

noticed it) backward to the time when it originated. This was not only a procedure

that ran contrary to the way that we researched and wrote The Classical Hollywood

Cinema, but it required a great deal more

space, more than we could spare in such a large tome. In Storytelling in

the New Hollywood, I was able to show both that the classical model persists

in many, probably most, mainstream American films, and that it has been a staple

of such films going back to the very era in which classical filmmaking was formulated.

1 :

Both

Janet and Kristin went on to publish later books with Princeton under Joanna’s

editorship.

2 :

Raymond Williams, “Base

and Superstructure in Marxist Cultural Theory,” Problems in Materialism

and Culture (London: New Left Books, 1980), pp. 47–48.

3 : Examples are The

Fiction Factory: or, From Pulp Row to Quality Street (New York: Random House,

1955), Quentin James Reynolds’ study of Street & Smith dime novels

and pulp magazines; and Mary Noel’s Villains Galore: The Heyday of

the Popular Story Weekly (New York: Macmillan, 1954).

4 : One of the benefits

of undertaking the Classical Hollywood Cinema project was meeting Rob

and his collaborator Judy Milhous.

5 : There is, for

example, F. M. Scherer’s Quarter Notes and Bank Notes: The Economics

of Music Composition in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries (Princeton:

Princeton University Press, 2004) and Lorenzo Bianconi and Giorgio Pestelli’s

anthology Opera Production and Its Resources, vol. 4 of The History of Italian

Opera (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998). One of the liveliest

studies in this vein is Ken Emerson’s Always Magic in the Air: The

Bomp and Brilliance of the Brill Building Era (Viking, 2005), which shows

how a pop-music company could develop its own forms, genres, and division of

labor.

6 :

See our Film

History: An Introduction, as well as Kristin’s study of German cinema

after World War I in Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood: German and American

Film after World War I (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2006) and

David’s work on the 1910s’ tableau style in On the History of

Film Style (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998) and Figures

Traced in Light (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005).

7 :

An exception is Colin Crisp’s superb study The Classic French Cinema

1930–1960 (Bloomington:

Indiana University Press, 1997).

8 :

The ongoing work of William Paul on screen formats and theatre architecture is

particularly promising. See “The K-Mart Audience at the Mall Movies,” Film

History 6,

4 (1994), pp. 487–501; “Screening Space: Architecture, Technology,

and the Motion Picture Screen,” Michigan Quarterly Review (Winter

1996), pp. 143–173; and “Breaking the Fourth Wall: ‘Belascoism,’ Modernism,

and a 3-D Kiss Me Kate,” Film History 16, 3 (2004), pp.

229–242.

9 :

Karl Popper, The

Open Society and Its Enemies, vol. II: The High Tide of Prophesy: Hegel,

Marx, and the Aftermath (London: Routledge, 1990), p. 19.

10 :

Some examples are James Lastra, Sound Technology and the American Cinema (New

York: Columbia University Press, 2000); Charles O’Brien, Cinema’s

Conversion to Sound: Technology and Film Style in France and the U.S. (Bloomington:

Indiana University Press, 2004); Scott Higgins, Harnessing the Technicolor

Rainbow: Color Design in the 1930s (New York: Columbia University Press,

2007) and Patrick Keating, Hollywood Lighting from the Silent Era to Film

Noir (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009).

11 :

In particular, Kathryn Kalinak, Settling the Score: Music and the Classical

Hollywood Film (Madison:

University of Wisconsin Press, 1992); Jeff Smith, The Sounds of Commerce (New

York: Columbia University Press, 1998); James Buhler, David Neumeyer, and Rob

Deemer, Hearing the Movies: Music and Sound in Film History (New York:

Oxford University Press, 2009)

12 :

“Dividing Labor for Production Control: Thomas Ince and the Rise of the

Studio System,” Cinema

Journal 18, no. 2 (Spring 1979): 16–25; “Mass-Produced Photoplays:

Economic and Signifying Practices in the First Years of Hollywood,” Wide

Angle 4, no. 2 (1981), 12–27; “‘Tame’ Authors and

the Corporate Laboratory: Stories, Writers, and Scenarios in Hollywood,“ The

Quarterly Review of Film Studies 8,

no. 4 (Fall 1983): 33–45; “Blueprints for Feature Films: Hollywood’s

Continuity Scripts,” in The American Film Industry, ed. Tino

Balio, 2nd ed. (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1985), pp. 173–92. The

same goes for my labeling of the post-1950 labor practice as the “package-unit” mode

of production.

13 : Perverse

Spectators: The Practices of Film Reception (NY: New York University

Press, 2000), pp. 28–42.

14 :

For example, Murray Smith, Engaging Characters: Fiction, Emotion and the

Cinema (NY:

Oxford University Press, 1995); Carl Plantinga and Greg M. Smith, eds., Passionate

Views: Film, Cognition, and Emotion (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University

Press).

15 :

David and Kristin do discuss generic motivation as one of the four motivations

for any film practice but a full-fledged analysis in relation to the normal articulation

of the term might have made the point clearer as well as how to apply Neoformalism

to smaller groups of films.

16 :

Andre Bazin, “La

Politique des auteurs,” in The New Wave, ed. Peter Graham (NY:

Doubleday, 1968), p. 154, quoted in CHC, p. 4.

17 : “Individualism

versus Collectivism: The Shift to Independent Production in the US Film

Industry,“ Screen, 24, no. 4–5 (July–October 1983), 68–79; (editor), The

Studio System (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press,

1995); “Authorship Approaches,” in Authorship and Film,

ed. David A. Gerstner and Janet Staiger (New York: Routledge, 2002), pp.

27–57; “Authorship Studies and Gus Van Sant,” Film Criticism 29,

no. 1 (Fall 2004): 1–22; “The Revenge of the Film Education Movement:

Cult Movies and Fan Interpretative Behaviors,” Reception: Texts, Readers,

Audiences, History 1 (Fall 2008): 43–69, http://www.english.udel.edu/RSSsite/Staiger.pdf; “Analysing

Self-Fashioning in Authoring and Reception,” in Ingmar Bergman Revisited:

Performance, Cinema and the Arts, ed. Maaret Koskinen (London: Wallflower,

2008), pp. 89–106.

18 :

See the accompanying booklet, The Rivals of D. W. Griffith: Alternate Auteurs

1913–1918 (Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, 1976).

19 :

Roger Holman, ed., Cinema 1900/1906: An Analytical Study by the National

Film Archive (London)

and the International Federation of Film Archives (Bussels: FIAF, 1982).

The filmography in the second volume was supervised by André Gaudrault.

20 :

Eileen Bowser, “The

Brighton project: an introduction,” Quarterly Review of Film Studies 4,

no. 4 (Fall 1979); André Gaudreault, “Temporalité et narrative:

le cinéma des premiers temps,” Études littéraires 13,

no. 1 (April 1980).

21 :

Robert C. Allen, Vaudeville

and Film 1895–1915: A Study in Media Interaction (PhD dissertation,

University of Iowa, 1977; rep. New York: Arno Press, 1980).

22 :

Nicholas Vardac, Stage

to Screen (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1949).

23 :

Charles Musser, “The

nickelodeon era begins: establishing the foundations for Hollywood’s mode

of representation,” Framework nos. 22/23 (Autumn 1983).

24 :

Barry Salt, “Film

form 1900–1906” Sight and Sound 47, no. 3 (Summer 1978) and “The

early development of film form,” Film Form, 1, no. 1 (Spring 1976),

and Film Style & Technology: History & Analysis (London: Starword,

1083).

25 :

Epes Winthrop Sargent, “The Photoplaywright,” Moving Picture

World 23,

no. 12 (20 March 1915), p. 1757.

26 : Breaking

the Glass Armor: Neoformalist Film Analysis (Princeton University Press,

1988), pp. 162–94.

27 :

There is no way to prove a negative, of course. David and I both, however, have

subsequently tried to find older references to “act” structures in

Hollywood films as we were researching Storytelling in the New Hollywood and The

Way Hollywood Tells It. They are so rare as to suggest

that they do not refer to a shared assumption about structure.

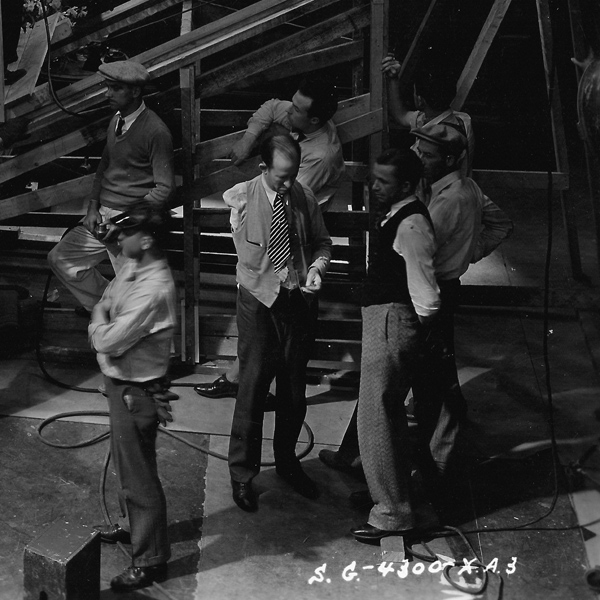

Filming Raffles (Goldwyn, 1930).

|

|