Murder Culture: Adventures in 1940s Suspense

March 2013

“I’m afraid.”

She had spoken aloud. She hadn’t meant to; she hadn’t wanted those words to come up from her throat to her lips. She hadn’t meant to think them, much less speak them. She didn’t want Gratia to have heard them.

But across the room the girl lifted her eyes from her book.

“What did you say?” she queried.

Opening of Dorothy B. Hughes’s Dread Journey

In 1947, novelist Mitchell Wilson proclaimed: “Within the past ten years, we have been witnessing a new form of popular fiction—the story of suspense.” 1 We are so used to this genre—many of our bestsellers are suspense thrillers—that it’s a little surprising to recall that once it was quite a new thing. On reflection, though, we might wonder: Was it really so new? Don’t all novels and short stories, indeed all narratives in popular media, depend on suspense? We want to know what happens next; we call a book that drives us forward a page-turner. But writers of the period began to distinguish this general sort of suspense from something more specific. 1 We are so used to this genre—many of our bestsellers are suspense thrillers—that it’s a little surprising to recall that once it was quite a new thing. On reflection, though, we might wonder: Was it really so new? Don’t all novels and short stories, indeed all narratives in popular media, depend on suspense? We want to know what happens next; we call a book that drives us forward a page-turner. But writers of the period began to distinguish this general sort of suspense from something more specific.

Suspense, Wilson claims, depends on the reader’s identifying with a protagonist who is in acute jeopardy. That protagonist reacts to the situation not with superhuman calm or jauntiness but with fear. By describing the situation and the character’s response to it, the writer can communicate fear directly to the reader, who, says Wilson, “is aware of his own cowardice.” The universality of fear as an emotion allows the reader to understand how the hero reacts, either by impulsively lashing out or by fleeing the situation.

What can best justify fear? The prospect of death. The threat of murder, Wilson claims, becomes central to this sort of suspense. It proves to the reader that there is no limit to the impending violence. 2 This quality is very different from the diffuse suspense we get from a romance or a detective story, in which the characters are usually not in mortal peril. 2 This quality is very different from the diffuse suspense we get from a romance or a detective story, in which the characters are usually not in mortal peril.

Sooner or later, though, the protagonist will have to come to overcome fear.

The framework of the suspense story is the continual struggle of the frightened protagonist to fight back and save himself in spite of his pervading anxiety, and in this respect he is truly heroic. The action of the story does not consist in mere activity, but in the hero’s change of mood in response to changing circumstances.

The suspense story, in this sense, is centrally about a character who starts out as a victim but who through brains and bravery can overcome the threat of death.

Wilson wasn’t alone in spotting the trend. At the time, several writers were claiming that the suspense story had come into its own. Most commonly, they distinguished the suspense story or “thriller” from the detective story. Wilson points out that the detective story relies upon curiosity rather than suspense—both for the reader and the detective, who tends to respond to murder with detached, intellectual calm. The sleuth is a puzzle-solver, and the reader is asked to join in the game of deciding “whodunit.” The reader doesn’t identify with the detective because the narration typically doesn’t give us access to the detective’s mind, or at least not at every point: something is kept back so the detective can reveal the solution at the climax.

Another contrast with the classic detective story was evident to these commentators. Instead of starting the plot with a dead victim, as the detective story tends to do, the suspense story builds up to the crime by centering on the potential victim—someone “enmeshed…in a web of circumstance.” 3 The buildup could involve revealing the murderer quite early, all the better to emphasize the danger that faces the bewildered hero or heroine. Indeed, part or all of the story could be told from the viewpoint of the killer. Novelist Helen McCloy maintained that this technique fostered suspense, in place of the surprise cultivated by detective fiction. 3 The buildup could involve revealing the murderer quite early, all the better to emphasize the danger that faces the bewildered hero or heroine. Indeed, part or all of the story could be told from the viewpoint of the killer. Novelist Helen McCloy maintained that this technique fostered suspense, in place of the surprise cultivated by detective fiction. 4 Charlotte Armstrong agreed, noting that “Surprise is not much fun.” 4 Charlotte Armstrong agreed, noting that “Surprise is not much fun.” 5 5

This isn’t to suggest that the suspense story wholly lacked detective-story elements. Indeed, there were often mysteries aplenty. Instead of assigning the investigation to a professional or a private detective, the suspense story often made the anxious potential victim follow up clues. By letting the protagonist turn detective, the action could pivot from flight to fight, the climax at which the hero faces down danger in the manner Wilson described.

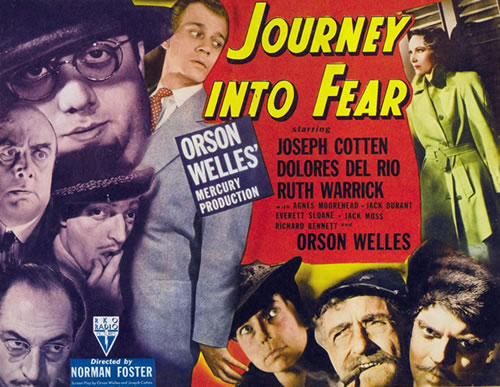

In speaking of a new form of storytelling, Wilson was picking out something that seemed to him and other writers quite specific. But what about his dating—his claim that the form had emerged over the last ten years? That would put the beginning of the suspense story at 1937 or 1938. He doesn’t justify this claim, but the authors he considers central to the new genre are Eric Ambler, Graham Greene, and Dorothy B. Hughes, all novelists who began writing crime fiction around that date. Wilson’s readers would have been aware of Ambler’s spy novels (most notably, The Mask of Dimitrios, 1939, and Journey into Fear, 1940), Greene’s criminal “entertainments” such as A Gun for Sale (aka This Gun for Hire, 1936), The Confidential Agent (1939), and The Ministry of Fear (1943), and Hughes’ tales of domestic murder and international espionage such as The So-Blue Marble (1940), The Bamboo Blonde (1941), The Fallen Sparrow (1942), and Dread Journey (1945). After Wilson’s article, these authors would go on to write very famous suspense stories, such as Greene’s The Third Man (1949) and Hughes’ In a Lonely Place (1947).

Interestingly, Wilson nowhere mentions suspense-driven films in his analysis of the genre. Yet by 1947 they were becoming a major form of Hollywood cinema. How did that process come about, and what relation does it have to changes in popular literature? We can understand the dynamic, I think, in two steps.

First, we can trace the 1940s model of suspense back to three relatively stable traditions that fed into it: the detective story, the domestic thriller, and the spy story. These suggest that Wilson’s ten-year window is somewhat too narrow. Then we can see how those traditions gained wide popularity in the 1940s as part of a diverse ecosystem of mystery narratives and informed what we came to recognize as the suspense thriller. Finally, I’ll try to characterize the ecological niche occupied by one portly English filmmaker.

Displacing the detective

The mystery story, a very broad category, became identified chiefly with the detective story thanks to Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes adventures. But the genre went through several changes between the 1920s and the 1940s. Central to the classic form was the series detective, the investigator who in a string of stories solved crimes through rational inference aided by brilliant intuition. The set of character roles was constant: the investigator(s); the criminal(s); the victim(s); and the bystanders, those suspects, witnesses, and helpers drawn into the inquiry. Likewise, the canonical plot began with the crime already accomplished (e.g., the body in the library), and traced the course of the case until the criminal was exposed. Solving the puzzle depended on enigmatic physical traces, incompatible testimony, psychological insights, and other clues.

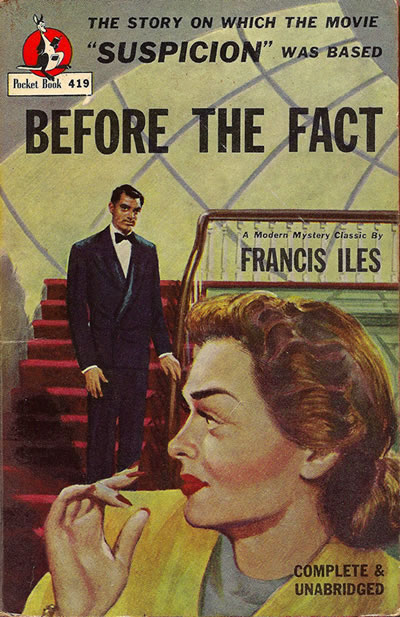

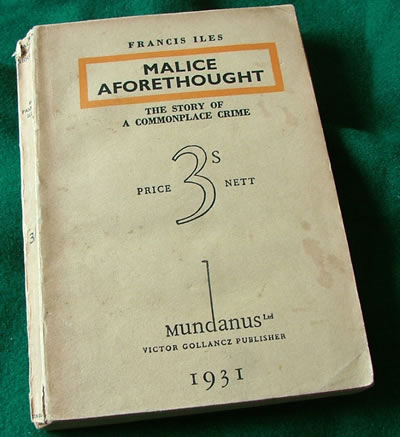

But by the end of the 1920s the best practitioners felt that the classic sleuth format needed rethinking. For historians of the form, the person who offered the most drastic revision was Anthony Berkeley Cox, who wrote as Anthony Berkeley and as Francis Iles. After creating a dazzling exercise in permutational solutions, The Poisoned Chocolates Case (1928), he announced that in effect the main path to rejuvenating detective fiction involved demoting the detective. Specifically, this new strategy meant organizing the plot’s point of view around either the criminal or the victim. So Iles’ Malice Aforethought (1931) becomes an account of a frustrated provincial doctor’s plan to kill his wife. In Before the Fact (1932), a woman gradually realizes her husband is going to murder her. Neither book is narrated in the first person, but each does confine itself wholly to the mind of the protagonist. Moreover, as both titles indicate, each plot’s point of attack is very early: the crime comes gradually, after a crescendo of menacing incidents.

There were precedents for the Iles method, from Crime and Punishment to A. P. Herbert’s House by the River (1920), C. S. Forester’s Payment Deferred (1926), and Berkeley’s The Second Shot (1929). Of the earlier experiments, most directly influential on mystery writers were the “inverted” detective stories by R. Austin Freeman gathered in The Singing Bone (1912). Freeman redesigned point of view by using the first part of the tale to recount the commission of the crime, chiefly from the criminal’s point of view, while part two traces the efforts of Dr. Thorndyke to solve the mystery. With the killer’s identity revealed at the outset, the story depends on generating curiosity about how Thorndyke will solve it (a dynamic continued in the television series Columbo). As for point of attack, the “inverted” plots begin well before the crime is committed, in order to establish motives and plans. In essence Iles’ novels lopped off the second half of the inverted tale, eliminating or minimizing the role of the investigation and concentrating wholly on the buildup to the crime—the panic and pressures suffered by the killer, or the suspicion and fear of the victim.

Coming from a skilled practitioner of whodunits, the two Iles books crystallized, at least in England, the creative option of designing a mystery plot focused around a would-be killer or victim. Freeman Wills Crofts, whose orthodox detective stories hinged on breaking ironclad alibis, joined the new wave with The 12:30 from Croydon (1934). Here the step-by-step planning and execution of a murder is told from the would-be killer’s standpoint. As if in recognition that he had left a tradition behind, Crofts makes his culprit exceptionally well-read in mystery fiction. He meditates in prison:

Somehow, alone there in the semi-darkness, the excellence of his own plans seemed less convincing than ever before. Stories he had read recurred to him in which the guilty had made perfect plans, but in all cases they had broken down. Those double tales of Austin Freeman’s! 6 6

Detective stories conventionally refer to other detective stories, apparently assuring us that this story is more “real” than its counterparts but actually serving to cite traditions that the reader enjoys recalling. Here Crofts acknowledges that Freeman’s “inverted” story made salient the possibility of a new gimmick: How will the criminal err in committing the crime?

Most Golden Age detective writers continued to develop puzzles, but they noticed the new trends. Dorothy Sayers acknowledged that an emphasis on psychology and the circumstances leading up to the crime had created “studies in murder” rather than straight detective tales. 7 Agatha Christie, whose talent was more protean than is usually acknowledged, blended before-the-fact plotting with mystery in And Then There Were None (1939), and she had a character in Towards Zero (1944) muse: 7 Agatha Christie, whose talent was more protean than is usually acknowledged, blended before-the-fact plotting with mystery in And Then There Were None (1939), and she had a character in Towards Zero (1944) muse:

I like a good detective story.…But, you know, they begin in the wrong place! They begin with the murder. But the murder is the end. The story begins long before that—years before sometimes—with all the causes and events that bring certain people to a certain place at a certain time on a certain day.…Even now…some drama—some murder to be—is in course of preparation. 8 8

Domesticating murder

Ten-Minute Alibi (1935).

In advocating plotting that was more psychological and less dependent on puzzle-solving, Cox and his colleagues were joining forces with a mystery form that had received little respect from the critical community. Since at least World War I, British and American writers had been cultivating what we might call the domestic thriller, a tale of mystery and danger in ordinary circumstances.

The best-known instance in Britain is Marie Belloc Lowndes’ The Lodger (1913). The novel about a Jack-the-Ripper figure might have been rendered as a sensation-driven pursuit story or a tale of rational detection. Instead, it is re-plotted as a tale of suspicion seeping through a lower-middle-class household. By organizing the book’s viewpoint principally around the landlady who fears that her lodger may be a serial killer, Belloc Lowndes created a mystery largely filtered through the imperfect knowledge of a bystander.

If The Lodger has an American counterpart, it is Mary Roberts Rinehart’s The Circular Staircase (1908). Again, the action is focused around a witness: the spinster Rachel Innes, who encounters the bizarre happenings in a rented summer house. Unlike The Lodger’s Mrs. Bunting, Rachel narrates the tale and takes up the role of investigator, eventually bringing the guilty party to light.

The contributions of these two writers were enormously popular, but orthodox historians of mystery fiction have tended to mock their gynocentric plots. Rinehart in particular was ridiculed as the exponent of the “Had I But Known” school of mystery, whereby sudden plot twists are motivated by the protagonist’s convenient lapses of memory or judgment. Worse, as one authoritative history puts it, is “the manner in which romantic complications are allowed to obstruct the orderly process of puzzle and solution.” 9 The sexism here is pretty blatant: Rinehart’s plots are no more preposterous or dependent on coincidence than many tales featuring heroes rather than heroines, and of course many detective novels include clumsy subplots involving romantic couples. 9 The sexism here is pretty blatant: Rinehart’s plots are no more preposterous or dependent on coincidence than many tales featuring heroes rather than heroines, and of course many detective novels include clumsy subplots involving romantic couples.

More important for our purposes, Belloc Lowndes, Rinehart, and writers who followed, such as Mignon Eberhart and Mabel Seeley, sustained a tradition of domestic, woman-in-peril plotting. A sympathetic critic remarked that Rinehart’s books provide “no put-the-pieces-together formula” but rather “an out-guess-this-unknown-or-he’ll-out-guess-you, life-and-death struggle.” 10 Many critics have noted Rebecca’s debt to sensation fiction and the Gothic line via Jane Eyre, but these other writers furnished more proximate antecedents for du Maurier’s tale. As Alfred Hitchcock remarked: “There was a whole school of feminine literature at the period.” 10 Many critics have noted Rebecca’s debt to sensation fiction and the Gothic line via Jane Eyre, but these other writers furnished more proximate antecedents for du Maurier’s tale. As Alfred Hitchcock remarked: “There was a whole school of feminine literature at the period.” 11 11

At almost exactly the same time, murder was being domesticated on the English and American stage. The major vogue seems to have come in the late 1920s, when, as a New York Times correspondent put it, London suffered “a theatrical crime wave…owing to a deluge of mystery plays and ‘thrillers.’” 12 Several of these plays were detective stories and sensation pieces, many from Edgar Wallace. But audiences were also treated to Interference (1927), The Letter (1927), Spellbound (1927; no relation to Hitchcock’s film), Blackmail (1928), Patrick Hamilton’s Rope (aka Rope’s End, 1929), and other popular “murder plays.” 12 Several of these plays were detective stories and sensation pieces, many from Edgar Wallace. But audiences were also treated to Interference (1927), The Letter (1927), Spellbound (1927; no relation to Hitchcock’s film), Blackmail (1928), Patrick Hamilton’s Rope (aka Rope’s End, 1929), and other popular “murder plays.”

The genre continued through the decade, with successes like the stage adaptation of Payment Deferred (1932), the ticking-clock drama Ten-Minute Alibi (1933), Without Witness (1934), The Two Mrs. Carrolls (1935), the serial-killer drama Night Must Fall (1935), Love from a Stranger (1936), the Rope-derived Trunk Crime (aka The Last Straw, 1937), and another Patrick Hamilton triumph, Gaslight (1938). The New York stage didn’t lag behind, importing several of these hits while adding Nine Pine Street (1933, based on the Lizzie Borden case), Double Door (1933, an anticipation of Rebecca), Invitation to a Murder (1934), and Kind Lady (1935). 13 13

A new label came to be attached to these dramas of home-bred homicide. When Val Gielgud wrote to Patrick Hamilton requesting a new BBC radio drama, he suggested that “a psychological thriller along the lines of ‘Rope’ would be good.” 15 The phrase came into currency during the 1930s to describe domestic thrillers in fiction, onstage, and onscreen, and plays began advertising themselves with the label. 15 The phrase came into currency during the 1930s to describe domestic thrillers in fiction, onstage, and onscreen, and plays began advertising themselves with the label. 15 15

Why the emphasis on psychology? Chiefly, I suspect, to distinguish these plays from the blood-and-thunder sensation of Edgar Wallace and the extroverted adventure of John Buchan. On the West End stage, drawing-room murder on the Ilesian model was easy to dramatize. If the plot divulges the plotter or killer from the start, the emphasis falls naturally on why the crime is committed and whether the guilty party will escape.

Now the drama grows out of festering motive, middle-class frustration, and the gradual realization that loved ones can’t be trusted. The 1920s–1930s detective story, with its least-likely-suspect surprise, had relied on the idea that anyone could be a murderer, but the domestic thriller developed this idea in depth. The theme was doubtless accelerated by much-publicized murders committed by solid citizens, notably Dr. H. H. Crippen, Loeb and Leopold, and baby-faced Sidney Fox (inspiration for Night Must Fall). These fictions replaced the Napoleonic crimes of sensation thrillers by a sense that humdrum life harbored lethal passions.

Hence a series of books organized around killers’ psychological states: Richard Hull’s The Murder of My Aunt (1935), Winifred Duke’s Skin for Skin (1935), Bruce Hamilton’s Middle Class Murder (1936), and James Ronald’s This Way Out (1939). Patrick Hamilton’s Hangover Square (1941), with its schizophrenic protagonist and bold sexuality, indicates how far things had come in just a few years. A parallel trend emerged in America. While the hard-boiled stories of Cain and Chandler gained most attention, other writers—again, mostly women—offered stories of lethally disturbed husbands (Elisabeth Sanxay Holding’s Death Wish, 1934, and Net of Cobwebs, 1935) and tangled domestic murder plots (Cora Jarrett’s Night over Fitch’s Pond, 1933).

What about focusing point of view around the victim? Psychology came to prominence there too. Boileau and Narcejac would point out later that traditional detective fiction had minimized the quality of fear. 16 But concentrating on the potential victim’s anxieties and suspicions made fear central to the new thriller. Not incidentally, most of the killers were male and many of their victims were female, continuing the woman-in-peril motif developed in Lowndes, Rinehart, and their followers, as well as in Before the Fact. The psychological thriller was able to reactivate the Bluebeard tradition, often making explicit reference to it. 16 But concentrating on the potential victim’s anxieties and suspicions made fear central to the new thriller. Not incidentally, most of the killers were male and many of their victims were female, continuing the woman-in-peril motif developed in Lowndes, Rinehart, and their followers, as well as in Before the Fact. The psychological thriller was able to reactivate the Bluebeard tradition, often making explicit reference to it.

Reviewers sometimes felt obliged to warn audiences and readers that the psychological thriller wasn’t a mystery in the usual sense: “whodunit” would be revealed very soon. Yet this foreknowledge didn’t dissipate interest. Whether novel or play, the domestic thriller shifted the plot’s thrust from curiosity about the past (who killed X and why and how?) to anticipation (will Y succeed in killing X and escape punishment?). As one writer explained in reviewing A. A. Milne’s play The Fourth Wall (1928):

Though we saw the murder, we do not know what little slip Carter may have made in the arrangement of the room or the concoction of his own and Laverick’s alibi. Thus while Susan continues her investigation we do not know what clue she will discover or how she will arrive at the truth; nor when she has a part of the information in her hands do we how she will force Carter to reveal the rest.

Here is scope for action enough, and not for action only but for as much drawing of character as is possible in the course of a narrative so full of events. The first act, which shows the murder, is admirable in its suspense and surprise. 17 17

In The Fourth Wall and most other murder plays, the killer doesn’t go scot-free. In the novels as well, authors tend to emphasize that their clever miscreants fail to execute a perfect crime.

I spy (All the worse for me)

As some detective-story writers, under the Iles influence, moved closer to the psychological thriller, another group of writers exploited suspense in tales of international intrigue. This trend seems to have been central to Mitchell Wilson’s 1947 intuition about the new thriller, for all three of his specific examples—Greene, Ambler, and Hughes—made their reputations in the spy genre.

Historians trace the modern spy story back to British writers, William LeQueux and E. Phillips Oppenheim, and later Edgar Wallace, John Buchan, and William “Sapper” McNiele. 18 These writers developed the basic conventions. Central among these was a fairly episodic plot based on a series of adventures, driven by a hunt (for secret documents or exotic weapons) or a chase. Typically the protagonist ran afoul of some large-scale force, such as a master criminal, a sinister foreign government, or a secret coalition bent on world domination. At the same time, the protagonist might also be sought by the police, a domestic intelligence agency, or some other force of law. The result was the “double chase,” in which the hero must elude both villains and the law, as in John Buchan’s The Thirty-Nine Steps (1915). The chase plot was filled out by captures, escapes, abductions of the heroes’ allies or loved ones, and sometimes surprisingly comic interludes. The conventions forged by these writers were ready-made for cinema, so it’s not surprising that some of the earliest feature films and serials in many countries were spy stories, such as Denmark’s Dr. Gar-el-Hama series, Louis Feuillade’s crime serials, and Lang’s Dr. Mabuse films and Spies (1928). 18 These writers developed the basic conventions. Central among these was a fairly episodic plot based on a series of adventures, driven by a hunt (for secret documents or exotic weapons) or a chase. Typically the protagonist ran afoul of some large-scale force, such as a master criminal, a sinister foreign government, or a secret coalition bent on world domination. At the same time, the protagonist might also be sought by the police, a domestic intelligence agency, or some other force of law. The result was the “double chase,” in which the hero must elude both villains and the law, as in John Buchan’s The Thirty-Nine Steps (1915). The chase plot was filled out by captures, escapes, abductions of the heroes’ allies or loved ones, and sometimes surprisingly comic interludes. The conventions forged by these writers were ready-made for cinema, so it’s not surprising that some of the earliest feature films and serials in many countries were spy stories, such as Denmark’s Dr. Gar-el-Hama series, Louis Feuillade’s crime serials, and Lang’s Dr. Mabuse films and Spies (1928).

Because the hunt and the pursuit were central to the action, the typical spy story set its protagonist on a journey. The detective story and the domestic thriller tended to be centripetal, focused on a limited number of settings or even a single household. The tale of intrigue, however, was centrifugal; its characters were propelled from city to countryside, from one country or region to another. Central scenes might take place on a train or on a highway. The Middle East, Russia, and Asia furnished exotic locales. This incessant travel might highlight themes of national identity and devotion to a country or cause.

The protagonist of the spy novel might be a professional secret agent or an independent adventurer who takes on a mission out of patriotism, personal loyalty, or a quest for excitement. Before the late 1930s, the spy thriller also contained some degree of humor, either in comic characters and dialect rendering or in a light-hearted approach to dangers, as seen in Agatha Christie’s Tuppence and Tommy Beresford series.

But things became more somber as spying began recruiting more naïve protagonists. Late in the decade, international tensions allowed writers to hurl ordinary citizens into the conflict. In Ambler’s Epitaph for a Spy (1938), the protagonist is a weak emigrant who is pressured into spying by brutal and bungling intelligence officials. Helen MacInnes’ Above Suspicion (1941) propels an Oxford couple into intrigue while they visit Europe for “one last look at peacetime” in 1939. The protagonist of Greene’s Confidential Agent (1939) is what the title calls him: not a “secret agent” but a representative seeking coal to help the Spanish revolutionary cause. Now that the plot depended on amateurs and innocents, missions can go amiss and the ending may be more glum than happy; Epitaph for a Spy and The Confidential Agent end with little sense of victory.

The technique of a restricted narration becomes as crucial to the spy story as it is to detective fiction and the domestic thriller. Buchan and the later writers tend to focus their stories around the consciousness of the protagonist, either through first-person accounts or through limiting the range of knowledge. In these books, we often know only as much as the hero or heroine does. Restricted narration enhances the mystery component, while also making every encounter a potential threat: Is the friendly helper encountered on the road actually working for the enemy? The limitations of knowledge make possible the conventional bluffs and double-crosses that create plot reversals typical of spy fiction, but they can also generate the anxiety—in protagonist and in reader—that Mitchell Wilson found central to the suspense story.

These three trends in popular fiction and drama seem most pertinent to the emergence of the 1940s suspense story. But they could not have exercised their influence had not America, home to Hollywood, gone mad for mystery and murder.

Murder for the millions

Hitchcock, Judith Anderson, and Joan Fontaine on the set of Rebecca.

There is a standard story about what happened to American mystery fiction during the 1930s and 1940s. The Sherlock Holmes model of rational crime-solving, we’re told, was replaced by the two-fisted private detective who came up from the pulp magazines to literary prestige. Like most such synopses, though, this one cuts some corners.

In popular literature, the adventures in deduction of Lord Peter Wimsey, Hercule Poirot, and Ellery Queen remained far more widely read than the chronicles of Sam Spade, Philip Marlowe, and other roughnecks. Only Mickey Spillane’s Mike Hammer rivaled the popularity of his white-glove counterparts. 19 Moreover, the standard outline plays down the syntheses between the puzzle-driven and action-driven plotting we find in the work of Rex Stout and Erle Stanley Gardner (hands down the most popular mystery writer of the 1940s). 19 Moreover, the standard outline plays down the syntheses between the puzzle-driven and action-driven plotting we find in the work of Rex Stout and Erle Stanley Gardner (hands down the most popular mystery writer of the 1940s). 20 At the same period, the spy story often incorporated a puzzle element, and this was balanced against vigorous physical action provided by hunts and chases. 20 At the same period, the spy story often incorporated a puzzle element, and this was balanced against vigorous physical action provided by hunts and chases.

Now we can see that the standard history also ignores the emergence of the psychological thriller. Mitchell Wilson’s remark in 1947 that the suspense story had come of age marks a dawning recognition that there was currently a form of mystery that steered a course between the puzzle and the hard-boiled adventure.

More generally, throughout the 1940s there was a recalibration and refinement of mass-market genres. Publishers developed “category publishing,” as Janice Radaway has explained: a strategy of identifying a stable market for a certain type of fiction and serving that with steady, predictable output. 21 Mysteries, Westerns, and romances, so identified, made up the bulk of U.S. genre fiction in the 1940s. Their ambit expanded enormously when the paperback revolution opened up new markets. 21 Mysteries, Westerns, and romances, so identified, made up the bulk of U.S. genre fiction in the 1940s. Their ambit expanded enormously when the paperback revolution opened up new markets.

Mystery, including detective stories, spy stories, and suspense fiction, was by far the most popular category. In 1940, 40% of all novels published were mysteries. 22 Serialized in slick magazines, then brought out in hardcover, then in cheaper editions, perhaps eventually to be the basis of radio plays or movies, mystery titles assured publishers solid returns and attained a degree of literary respectability at the same time. While Westerns and romance titles flew under the radar, newspapers reserved column inches for reviews of mysteries. Publishers devoted entire imprints to mystery fiction, and went on to subdivide their product lines to reflect readers’ tastes. Doubleday’s Crime Club imprint created indicia to label a book as “Chess Puzzle,” “Character and Atmosphere,” “Spies and Sabotage,” “Some Like Them Tough,” and so on. Simon and Schuster’s “Inner Sanctum” logo marked “a novel of suspense, a novel of crime and punishment rather than a novel of crime and detection.” 22 Serialized in slick magazines, then brought out in hardcover, then in cheaper editions, perhaps eventually to be the basis of radio plays or movies, mystery titles assured publishers solid returns and attained a degree of literary respectability at the same time. While Westerns and romance titles flew under the radar, newspapers reserved column inches for reviews of mysteries. Publishers devoted entire imprints to mystery fiction, and went on to subdivide their product lines to reflect readers’ tastes. Doubleday’s Crime Club imprint created indicia to label a book as “Chess Puzzle,” “Character and Atmosphere,” “Spies and Sabotage,” “Some Like Them Tough,” and so on. Simon and Schuster’s “Inner Sanctum” logo marked “a novel of suspense, a novel of crime and punishment rather than a novel of crime and detection.” 23 23

As this ecosystem expanded and diversified, commentators began to distinguish suspense stories from other forms of thriller. The radio program Suspense began regular broadcasting in 1942. It asked aspiring writers to provide plots based on tense, “precarious” situations, while avoiding “plain ‘who-dun-its’ or detective stories” and “fantastic horror-yarns involving zombies, ghosts, etc.” 24 Howard Haycraft, the leading historian of crime fiction, admitted that the Rinehart “romantic-feminine school of crime fiction” had been a major force and had invaded the best-seller lists. Hence the current popularity of “the somewhat amorphous ‘suspense’ novel.” 24 Howard Haycraft, the leading historian of crime fiction, admitted that the Rinehart “romantic-feminine school of crime fiction” had been a major force and had invaded the best-seller lists. Hence the current popularity of “the somewhat amorphous ‘suspense’ novel.” 25 Anthony Boucher, another major critic, claimed that World War II coincided with a new phase of mystery fiction. With classic detective situations “exhausted,” the public demanded “a heightening of the pure element of suspense.” Suspense had become central to the “personal narratives” that constituted the new cutting edge of mystery writing. 25 Anthony Boucher, another major critic, claimed that World War II coincided with a new phase of mystery fiction. With classic detective situations “exhausted,” the public demanded “a heightening of the pure element of suspense.” Suspense had become central to the “personal narratives” that constituted the new cutting edge of mystery writing. 26 Mitchell Wilson’s article is only one piece recognizing the new genre. 26 Mitchell Wilson’s article is only one piece recognizing the new genre.

If you had to pick a single book that shifted U.S. mystery publishing toward psychological suspense, it would probably be Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca. (Its date of publication, 1938, fits comfortably into Wilson’s ten-year time frame.) Upon publication it immediately became a bestseller, and by the end of the 1940s it had sold over a million copies, making it the most successful mystery novel of the era. 27 In fact, it was hardly recognized as a mystery novel. Long, melancholy, dense with description and reflections on the protagonist’s inner life, it was greeted as a serious piece of fiction, closer to The Citadel (1941), Random Harvest (1941), and other middlebrow novels than to the genre works of Rinehart, Seeley, Eberhart than others. With its echoes of Jane Eyre, Rebecca provided a model for the “romantic suspense” novel that would come to prominence in the 1950s and eventually become the Harlequin romance of our day. 27 In fact, it was hardly recognized as a mystery novel. Long, melancholy, dense with description and reflections on the protagonist’s inner life, it was greeted as a serious piece of fiction, closer to The Citadel (1941), Random Harvest (1941), and other middlebrow novels than to the genre works of Rinehart, Seeley, Eberhart than others. With its echoes of Jane Eyre, Rebecca provided a model for the “romantic suspense” novel that would come to prominence in the 1950s and eventually become the Harlequin romance of our day.

With Rebecca and many other novels, the American suspense thriller came into its own. Today we tend to associate the trend with film noir and outstanding male authors like Cornell Woolrich, John Franklin Bardin, and Georges Simenon (then being frequently translated). Again, however, the trend was also shaped by Vera Caspary, Dorothy B. Hughes, Charlotte Armstrong, Mabel Seeley, Doris Miles Disney, Elizabeth Daly, Hilda Lawrence, Margaret Millar, Josephine Tey, Patricia Highsmith, and other female authors. As the “inverted” and multi-perspectival detective story had pushed some English practitioners toward psychological mystery, so too did many of these women novelists abandon their series detectives and shift toward pure suspense.

Cinema followed the trend. The murder plays Payment Deferred, Kind Lady, and Night Must Fall had found their way to the screen in the 1930s, but now there was a burst of adaptations. Gaslight was filmed in 1944, The Two Mrs. Carrolls and Love from a Stranger in 1947. Other revivals included the Gothic classics Jane Eyre (1944) and The Woman in White (1948) and the Edwardian books The Lodger (1944) and The House by the River (1950).

Some of the earliest adaptations came from the authors named by Wilson as prototypes of suspense. Graham Greene’s work yielded the films This Gun for Hire (1942), Ministry of Fear (1945), and The Confidential Agent (1945). Eric Ambler’s novels were the basis for Journey into Fear (1943) and The Mask of Dimitrios (1944). The less-known Dorothy B. Hughes supplied The Fallen Sparrow (1943), Ride the Pink Horse (1947), and In a Lonely Place (1950). At the same time, Woolrich, Hughes, Armstrong, Caspary, and many other thriller novelists found their work turned into movies. 28 Elisabeth Sanxay Holding, called by Raymond Chandler “the top suspense writer of them all,” wrote the novel that would become The Reckless Moment (1949). 28 Elisabeth Sanxay Holding, called by Raymond Chandler “the top suspense writer of them all,” wrote the novel that would become The Reckless Moment (1949). 29 29

Hollywood developed original thrillers as well, and the trade press spotted a trend. A 1944 Variety article claimed that

The typical tale in the new genre crawls with living horror, is eerie with something impending, and socks its suspense thrill well along toward the middle of the story, instead of doing the crime victim in at the beginning and then building a whodunit and a detective quiz as the element of suspense. 30 30

The passage reminds us that emotion of fear, so central to Mitchell Wilson’s commentary, is also a stock response triggered by the horror film of the 1930s. In 1947 Wilson felt no need to specify that the fear conjured up by the suspense story was not akin to that in horror or fantasy films: the cause was not a monster or a supernatural being. Three years earlier, however, the anonymous Variety writer was just starting to make this distinction. The article takes Rebecca (1940), Phantom Lady, Gaslight, Dark Waters (1944), Mask of Dimitrios, Hangover Square (1945), and even The Picture of Dorian Gray (1945), as examples of the “new horrifier.” Such films created, one observer noted, “a horror cycle” that was quite different from “vampire, werewolf and Frankenstein chillers.” 31 31

Lumping all these "suspense" films together seems a bit odd today. Aren’t Gaslight and Dark Waters really Gothics? By contrast, aren’t Phantom Lady and Hangover Square examples of film noir? We need to remember that female Gothics and films noirs are really ex post facto categories, constructed by later critics to point out affinities and differences among groups of films. These categories didn’t exist for contemporaries, and filmmakers and writers of the time carved things up rather differently.

Many of the 1940s films’ plots, as we’d expect, put women in danger in a forbidding household. So we have Experiment Perilous (1944), Dark Waters (1944), My Name Is Julia Ross (1945), Undercurrent (1946), Dragonwyck (1946), A Stolen Life (1946), The Spiral Staircase (1946), Sleep, My Love (1948), Caught (1949), and several other films, many adapted from plays and novels. When a Hollywood’s psychological thriller focused on a male protagonist it could yield something like Hangover Square, The Woman in the Window (1944), Conflict (1945), Scarlet Street (1945), The Suspect (1945), The Chase (1946), They Won’t Believe Me (1947), The Big Clock (1948), Take One False Step (1949), and The Second Woman (1950).

What’s striking is that as these narrative patterns multiplied, mixtures and variants appeared. The plot of Phantom Lady, novel and film, depends on a properly victimized, perhaps paranoid noir hero; but he is rescued by his girlfriend. Instead of murderous husbands we find equally manipulative women targeting husbands, wives, and engaged couples (A Guest in the House, 1944; Strange Impersonation, 1946; Leave Her to Heaven, 1946). Even the “Gothic” plots exhibit a lot of variety. In Dark Waters, the villain isn’t the husband but an entire family conspiring against the bride. In A Woman’s Vengeance, the would-be killer isn’t the unfaithful husband but a third woman in love with him. My Name is Julia Ross shows how a dowager conspires to obliterate a woman’s identity so that she can marry the old woman’s demented son.

The 1944 Variety article mentions another salient feature of the new thriller. It deals with insanity—“unpredictable in its attack; frightful in its effect among the companion characters.” 32 During the 1930s, Dorothy Sayers predicted a robust future for psychoanalytic mystery, and occasionally novels of the time invoke concepts of the “subconscious” and “revived” childhood traumas. 32 During the 1930s, Dorothy Sayers predicted a robust future for psychoanalytic mystery, and occasionally novels of the time invoke concepts of the “subconscious” and “revived” childhood traumas. 33 American detective stories of the 1940s dabbled in the trend more overtly; one of the earliest seems to be Lawrence Treat’s 1943 O as in Omen, which makes its sleuth a psychiatrist who interprets not only suspects’ dreams but his own. Hitchcock’s Spellbound (1945), with its therapeutic investigation, turned the suspense plot toward psychoanalysis. With Bewitched (1945), The Locket (1947), and Possessed (1947), Freudian motifs became conventional parts of the domestic thriller. Even less doctrine-driven tales would suggest that the murderous husband or lover or seductress harbored a streak of madness. 33 American detective stories of the 1940s dabbled in the trend more overtly; one of the earliest seems to be Lawrence Treat’s 1943 O as in Omen, which makes its sleuth a psychiatrist who interprets not only suspects’ dreams but his own. Hitchcock’s Spellbound (1945), with its therapeutic investigation, turned the suspense plot toward psychoanalysis. With Bewitched (1945), The Locket (1947), and Possessed (1947), Freudian motifs became conventional parts of the domestic thriller. Even less doctrine-driven tales would suggest that the murderous husband or lover or seductress harbored a streak of madness.

By the late 1940s, the suspense story was a major genre. In her survey of the movie colony, Hortense Powdermaker noted the recent vogue for “psychological murder thrillers” and the rise of suspense as a factor in A pictures. 34 Instead of a detective story, remarked another writer, Hollywood could now offer “adult and exciting screen drama on the mystery framework, with emphasis on character and suspense.” 34 Instead of a detective story, remarked another writer, Hollywood could now offer “adult and exciting screen drama on the mystery framework, with emphasis on character and suspense.” 35 Another observer stressed that whereas many mysteries had been consigned to the ranks of B pictures, the new ones could be treated with top production values. 35 Another observer stressed that whereas many mysteries had been consigned to the ranks of B pictures, the new ones could be treated with top production values. 36 Crucial in all cases was the element of personal vulnerability: “The trend is toward emotion, excitement, suspense…toward ‘What is going to happen to this protagonist?’” 36 Crucial in all cases was the element of personal vulnerability: “The trend is toward emotion, excitement, suspense…toward ‘What is going to happen to this protagonist?’” 37 37

The Master

The Lady Vanishes (1938).

Sharp-eyed readers will have noticed that nearly all my examples of suspense films come from the years 1944 onward. What about the years before?

Examples of suspense pictures are curiously hard to find in those years. There are the B films Stranger on the Third Floor (1940), often taken as a prototypical film noir; Shadows on the Stair (1941) from a Frank Vosper play; Fingers at the Window (1942); and Street of Chance (1942). The rare A pictures we might consider include Ladies in Retirement (1941), but featuring minor players; I Wake Up Screaming (1941), a somber detective film narrated largely from the standpoints of witnesses and suspects; and two upper-tier spy films of 1943, Journey into Fear and Above Suspicion. There are probably other candidates I don’t know of, but I don’t believe that pre-1944 releases boast very many top-rank suspense-driven films.

Except of course, for the films directed by Alfred Hitchcock.

So far my story must seem a case of Hamlet without the Prince. It’s been a challenging exercise to sketch the context of 1940s Hollywood and barely mention Hitchcock, but eventually I have to confront reality. The “missing” suspense films of the early 1940s are by Hitchcock: Rebecca (1940), Foreign Correspondent (1940), Suspicion (1941), Saboteur (1942), and Shadow of a Doubt (1943). And it seems likely that they strongly influenced what would follow.

Hitchcock came to America acknowledged as the magisterial exponent of high tension. In a 1936 article in the Times of London, a reviewer writes, “Mr. Hitchcock’s long and strong suit is suspense.” 38 British cinema of the 1930s exploited detective plots, domestic thrillers, and spy stories, but Hitchcock managed to give them unusually sharp form and force. 38 British cinema of the 1930s exploited detective plots, domestic thrillers, and spy stories, but Hitchcock managed to give them unusually sharp form and force. 39 Murder! (1930) respects the detective-story premises of the source novel. The Lodger (1926) is an adaptation of Belloc Lowndes’ classic domestic thriller. Blackmail (1929) also relies on conventions of that genre: the killer’s identity is known at the start, and her task is to escape punishment. Above all there were the five spy films in the second half of the 1930s. Although The Secret Agent (1936) centers on a professional spy, the others show ordinary people caught up in international intrigue: the family in The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934) and a couple on a train in The Lady Vanishes (1938). Even the Richard Hannay of The 39 Steps (1935) seems more an ordinary person than the adventure-loving gentleman of the Buchan books. Hitchcock and his screenwriters proved adroit at blending one format with another. Young and Innocent (1937) is derived from a detective novel, but the film divulges the murderer’s identity in the first scene in order to set up a double-barreled pursuit. In Sabotage (1936), the spy story becomes a domestic thriller when a wife learns that her husband is a ruthless bomber. 39 Murder! (1930) respects the detective-story premises of the source novel. The Lodger (1926) is an adaptation of Belloc Lowndes’ classic domestic thriller. Blackmail (1929) also relies on conventions of that genre: the killer’s identity is known at the start, and her task is to escape punishment. Above all there were the five spy films in the second half of the 1930s. Although The Secret Agent (1936) centers on a professional spy, the others show ordinary people caught up in international intrigue: the family in The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934) and a couple on a train in The Lady Vanishes (1938). Even the Richard Hannay of The 39 Steps (1935) seems more an ordinary person than the adventure-loving gentleman of the Buchan books. Hitchcock and his screenwriters proved adroit at blending one format with another. Young and Innocent (1937) is derived from a detective novel, but the film divulges the murderer’s identity in the first scene in order to set up a double-barreled pursuit. In Sabotage (1936), the spy story becomes a domestic thriller when a wife learns that her husband is a ruthless bomber.

In both England and the U.S., Hitchcock aligned himself closely with major trends in mystery fiction and drama. His reading tastes ran to Belloc Lowndes and John Buchan. 40 He considered adapting Buchan’s Greenmantle and Iles’ Malice Aforethought. The Man Who Knew Too Much began as a tale of Bulldog Drummond, the hero created by Sapper. Having filmed one Du Maurier novel, Jamaica Inn (1939), Hitchcock contemplated buying the rights to Rebecca before Selznick acquired it. 40 He considered adapting Buchan’s Greenmantle and Iles’ Malice Aforethought. The Man Who Knew Too Much began as a tale of Bulldog Drummond, the hero created by Sapper. Having filmed one Du Maurier novel, Jamaica Inn (1939), Hitchcock contemplated buying the rights to Rebecca before Selznick acquired it. 41 Two of his films featured the actor Frank Vosper, co-author of the significant murder play Love from a Stranger. Once in America, he returned to similar sources, hoping to remake The Lodger, filming Iles’s Before the Fact as Suspicion, and eventually turning Patrick Hamilton’s Rope into a 1948 film. There were personal affinities as well. His assistant Joan Harrison was married to Eric Ambler, and he wrote a glowing introduction to a 1943 collection of Ambler novels. 41 Two of his films featured the actor Frank Vosper, co-author of the significant murder play Love from a Stranger. Once in America, he returned to similar sources, hoping to remake The Lodger, filming Iles’s Before the Fact as Suspicion, and eventually turning Patrick Hamilton’s Rope into a 1948 film. There were personal affinities as well. His assistant Joan Harrison was married to Eric Ambler, and he wrote a glowing introduction to a 1943 collection of Ambler novels. 42 42

With the exception of the comedy Mr. and Mrs. Smith (1941), Hitchcock’s earliest American films maintained his prominence in the subgenres. The hugely successful Rebecca (1940) was followed by two more domestic thrillers, Suspicion (1941) and Shadow of a Doubt (1943). Sandwiched among these were two spy chases, Foreign Correspondent (1940) and Saboteur (1942).

Very quickly his work set the benchmark. Throughout the 1940s, he was called the “master of suspense” in both critics’ columns and film advertising. The term reappeared in trade advertisements for Shadow of a Doubt, Lifeboat, and Spellbound. 43 A 1941 review of Ladies in Retirement praised it for providing Hitchcockian suspense. 43 A 1941 review of Ladies in Retirement praised it for providing Hitchcockian suspense. 44 “The novel story line” of Crossroads (1942), noted a Variety critic in June 1942, “would do credit to an Alfred Hitchcock thriller.” 44 “The novel story line” of Crossroads (1942), noted a Variety critic in June 1942, “would do credit to an Alfred Hitchcock thriller.” 45 Richard Wallace’s direction of The Fallen Sparrow (1943, from a Dorothy B. Hughes novel) was said to be “reminiscent of the Hitchcock touch.” 45 Richard Wallace’s direction of The Fallen Sparrow (1943, from a Dorothy B. Hughes novel) was said to be “reminiscent of the Hitchcock touch.” 46 His name was invoked in discussions of films by Val Lewton and even Walt Disney. 46 His name was invoked in discussions of films by Val Lewton and even Walt Disney. 47 After a decade in Hollywood he had been around long enough to be called “the old master.” 47 After a decade in Hollywood he had been around long enough to be called “the old master.” 48 48

Hitchcock worked to promote his brand. 49 In interviews and public talks he differentiated the detective story from his sort of thriller, often stressing that distinction between suspense and surprise that was picked up by Charlotte Armstrong, Helen McCloy, and other commentators on the emerging suspense genre. 49 In interviews and public talks he differentiated the detective story from his sort of thriller, often stressing that distinction between suspense and surprise that was picked up by Charlotte Armstrong, Helen McCloy, and other commentators on the emerging suspense genre. 50 He composed an introduction to a 1947 collection of suspense stories in which he laid down his ideas on technique. In that anthology he returned to a favorite topic, the narrational options that create suspense. Much of suspense comes down to range of knowledge. “The author may let both reader and character share the knowledge of the nature of the dangers which threaten….Sometimes, however, the reader alone may realize that peril is in the offing, and watch the characters moving to meet it in blissful ignorance and disquieting unconcern.” 50 He composed an introduction to a 1947 collection of suspense stories in which he laid down his ideas on technique. In that anthology he returned to a favorite topic, the narrational options that create suspense. Much of suspense comes down to range of knowledge. “The author may let both reader and character share the knowledge of the nature of the dangers which threaten….Sometimes, however, the reader alone may realize that peril is in the offing, and watch the characters moving to meet it in blissful ignorance and disquieting unconcern.” 51 Hitchcock continued to pronounce on principles of suspense throughout the 1940s, applying them to whatever project he had in hand. (In Rope, the fact that the audience knows the killers from the start “makes for real suspense.” 51 Hitchcock continued to pronounce on principles of suspense throughout the 1940s, applying them to whatever project he had in hand. (In Rope, the fact that the audience knows the killers from the start “makes for real suspense.” 52) He became the foremost practitioner and theorist of the new genre. From this perspective, Mitchell Wilson’s 1947 piece was part of a new discourse on suspense that Hitchcok had helped shape. 52) He became the foremost practitioner and theorist of the new genre. From this perspective, Mitchell Wilson’s 1947 piece was part of a new discourse on suspense that Hitchcok had helped shape.

His influence extended beyond cinema. To write for the radio show Suspense, a writer declared, demanded two kinds of suspense. “Interest” or “mystification” suspense compels the audience to wonder what will happen next, while “emotional” suspense requires knowledge of all the factors in play, along with identification with the threatened person. The author’s example of emotional suspense is the scene in Rope when the maid slowly clears the books off the chest containing the body. Indeed, the program was explicitly designed to bring to radio “the particular kind of suspense developed in pictures by Alfred Hitchcock.” 53 53

The Master’s problems, and some solutions

Above Suspicion (1943).

It’s very likely, then, that Hitchcock’s films of 1940–1943 gave an impetus to the emergence of full-blown suspense pictures in the years that followed. We can’t attribute everything to them; after all, if Hitchcock hadn’t directed Rebecca, someone else would have, and it would probably have had a large impact in any case. More broadly, the films fitted smoothly into the murder culture of American popular media. Still, the films provided high standards of quality and meticulous models of plot and style that other filmmakers could learn from.

In following Hitchcock’s models and other efforts of the early forties, the studios couldn’t turn on a dime. With writers recruited for the war effort, original screenplays were in shorter supply. Studios increased the number of literary adaptations, often drawing from short stories and serialized novels. Once a property was found, it typically took at least a year to develop into a finished film, and very often a story went through several years of development. 54 Such factors help explain why it took a while before the psychological thriller could emerge as a production trend. 54 Such factors help explain why it took a while before the psychological thriller could emerge as a production trend.

When it did, in calendar 1944, Hitchcock’s example remained inescapable. Yet counter-forces developed. Once the suspense story developed, was he to be its only master?

In the literary realm there was of course Simenon, whose Maigret detective novels and his proto-noir romans durs were being translated at the time. Fritz Lang, dubbed by Variety “a master at maintaining high suspense,” 55 had like Hitchcock made his reputation with crime thrillers before arriving in America, and his Hollywood work of the 1940s soon paralleled the Englishman’s: espionage thrillers (Man Hunt, Hangmen Also Die!, Ministry of Fear, Cloak and Dagger) alongside domestic ones. Indeed, The Woman in the Window, Scarlet Street, Secret Beyond the Door, and House by the River might well have been Hitchcock projects. There was also Robert Siodmak. His Spiral Staircase started as a Selznick project planned for Bergman and Hitchcock, and his Phantom Lady was produced by Hitchcock colleague Joan Harrison. Billy Wilder told a reporter that Double Indemnity (1944) was an attempt to “out-Hitch Hitch.” 55 had like Hitchcock made his reputation with crime thrillers before arriving in America, and his Hollywood work of the 1940s soon paralleled the Englishman’s: espionage thrillers (Man Hunt, Hangmen Also Die!, Ministry of Fear, Cloak and Dagger) alongside domestic ones. Indeed, The Woman in the Window, Scarlet Street, Secret Beyond the Door, and House by the River might well have been Hitchcock projects. There was also Robert Siodmak. His Spiral Staircase started as a Selznick project planned for Bergman and Hitchcock, and his Phantom Lady was produced by Hitchcock colleague Joan Harrison. Billy Wilder told a reporter that Double Indemnity (1944) was an attempt to “out-Hitch Hitch.” 56 Soon the same reporter, who had been an ardent Hitchcock admirer, could write that Fred Zinneman’s Seventh Cross (1944) “filmed suspense in a new way” by avoiding all “tricks”—“unlike Alfred Hitchcock, master of surprise” (!). 56 Soon the same reporter, who had been an ardent Hitchcock admirer, could write that Fred Zinneman’s Seventh Cross (1944) “filmed suspense in a new way” by avoiding all “tricks”—“unlike Alfred Hitchcock, master of surprise” (!). 57 57

Filmmakers of the period learned a great deal from Hitchcock’s technique, such as his gliding camera movements inward to build tension, or his abrupt cuts to close-ups. There was even open copying. Lifting from the Albert Hall climax of The Man Who Knew Too Much, Richard Whorf’s Above Suspicion (1943) presents an assassination during an orchestra performance, with the gunshot masked by a blast of music. 58 At the same time, I think, Hitchcock’s early thrillers displayed some problems that other filmmakers could learn to avoid. Take Rebecca and Suspicion, the two tales of uxorial mistrust. 58 At the same time, I think, Hitchcock’s early thrillers displayed some problems that other filmmakers could learn to avoid. Take Rebecca and Suspicion, the two tales of uxorial mistrust.

Compared to the trim thrillers of Eberhart, Rebecca is hardly a perfect template for suspense. Its plot evokes mystery but in a rather leisurely way, gradually crystallizing questions about how Rebecca died and why widower Maxim de Winter behaves brusquely. The emphasis falls on the nameless heroine’s pangs of naivete and inferiority when thrust into a wealthy milieu. Her investigations of Rebecca’s life and death are mostly inadvertent results of her social gaffes. Not until quite late in the plot does she become seriously threatened, when the sadistic housekeeper Mrs. Danvers urges the distraught girl to fling herself out a window.

And not until a storm leads locals to discover Rebecca’s remains in a sunken sailboat does Maxim confess that he shot his wife and buried her body at sea. Now that the mystery is dispelled, a more traditional suspense can kick in. Maxim must bluff the coroner’s inquest and evade the blackmailing scheme of Rebecca’s lover Favell. Maxim and the heroine are saved, again more or less accidentally, but with the Manderley estate destroyed, they end their lives in a seedy French hotel and brood on their lost Manderley and their hollow marriage.

Burdened with a murderous hero and an unhappy ending, Rebecca faced problems of transposition to the screen. To placate the Hays Office, Selznick and Hitchcock modified the plot to make Rebecca’s death an accident, covered up by Maxim. On the whole, other changes made for the film streamlined the action, excising the musings that fill the book and building up the suspense, chiefly through the pressures the sinister Mrs. Danvers brings to bear on the new wife. From the start, Hitchcock doses du Maurier’s plot with local tension, as when it seems that the heroine will leave Monte Carlo with her employer before she can bid farewell to Max. The cinematography turns Manderley into an oversized mausoleum with doorknobs set at the level of the heroine’s shoulders. Hitchcock seized the opportunity to hint at ominous secrets harbored in the vast rooms and corridors. Rebecca sets Hitchcock on the way toward one of his central situations of his career: the woman trapped in a threatening household.

Rebecca poses the questions: Whom have I married? What is his past? What am I to him? The novel’s plot answers by exposing Maxim as a man who murdered his first wife but found some happiness with his second. Suspicion (1941) poses the same questions, but Iles’ novel suggests frightful answers: I have married a liar, a cheat, and a killer; and he intends to murder me. Again, the film’s ending had to be fudged. Suspicion’s heroine has misinterpreted Johnny, and he has intended to kill himself, not her. The reconciliation is even more of a letdown than in the Rebecca instance. Variety responded sourly:

In switching tragic ending of Francis Iles’ novel in favor of a happy finale, Hitchcock and his scripters devised a most inept and inconclusive windup that fails to measure up to the dramatic intensity of preceding footage, and this doesn’t reach the climax expected. In this respect, picture structure is deficient, and it is obvious that the writers endeavored to toss in the happy ending in a few hundred feet and let it go at that. 59 59

Later filmmakers solved the problem of the enigmatic husband in a simpler fashion: Let the husband be a murderer, and let the wife escape. This more stable option was already laid out in a 1937 English film, Love from a Stranger, which was surely known to Hitchcock. Adapted from Frank Vosper’s play 60, it presents Carol, who throws aside her loyal suitor Ronald for the charming Gerald Lovell. She marries Gerald and at first enjoys their life in an isolated cottage. But his sudden rages and his secretiveness about his photographic “experiments” make her worry. Breaking with Carol’s range of knowledge about halfway through the film, the narration shows Gerald in the cellar burning a photograph of her. Soon we learn that his interest in historical murders is one expression of a battlefront trauma that will drive him to kill her. Gradually Carol’s suspicions crystallize. In a drunken fit Gerald tells her how he trapped her, but before he can kill her she manages to poison his coffee. He collapses and Ronald arrives in time to console a sobbing Carol. 60, it presents Carol, who throws aside her loyal suitor Ronald for the charming Gerald Lovell. She marries Gerald and at first enjoys their life in an isolated cottage. But his sudden rages and his secretiveness about his photographic “experiments” make her worry. Breaking with Carol’s range of knowledge about halfway through the film, the narration shows Gerald in the cellar burning a photograph of her. Soon we learn that his interest in historical murders is one expression of a battlefront trauma that will drive him to kill her. Gradually Carol’s suspicions crystallize. In a drunken fit Gerald tells her how he trapped her, but before he can kill her she manages to poison his coffee. He collapses and Ronald arrives in time to console a sobbing Carol.

Ronald plays a secondary role in Love from a Stranger. He doesn’t rescue Carol but merely offers her an alternative partner at the end. Hollywood’s later versions of the plot turned the other man into what Diane Waldman has called a “helper male”—a figure who can save the heroine and supply a romantic alliance once the murderous husband has been eliminated. 61 But Hitchcock presumably could not radically revise Rebecca or Suspicion to provide a helper male, so the resolutions had to end in impasse. Interestingly, when Hamilton’s play Gaslight made it to film in the U.S. (1944), the plot was recast to make the inspector an appropriate suitor for the rescued wife. 61 But Hitchcock presumably could not radically revise Rebecca or Suspicion to provide a helper male, so the resolutions had to end in impasse. Interestingly, when Hamilton’s play Gaslight made it to film in the U.S. (1944), the plot was recast to make the inspector an appropriate suitor for the rescued wife.

Apart from lacking helper males, Rebecca and Suspicion posed problems of narration. Love from a Stranger provided a wide frame of knowledge. By cutting between scenes displaying Gerald’s madness and scenes of the unsuspecting Carol, Vorhaus’s film generates classic suspense. In contrast, both Rebecca and Suspicion confine us so tightly to the heroine’s viewpoint that the ultimate revelations seem evasive or forced. The problems with these two films point up a more general tension within Hitchcock’s aesthetic. Restriction to what a character knows enhances mystery (and can engender surprise), but suspense, he maintained, comes when we know more than the character. 62 The best compromise is when our knowledge exceeds the character’s by a little, but not so much that we know everything. Hence the moments that fall outside Jeff’s range of knowledge in Rear Window, the judicious inserted scene of the agency meeting in North by Northwest, and other instances in which Hitchcock slightly widens our range of knowledge, often in a teasing way. 62 The best compromise is when our knowledge exceeds the character’s by a little, but not so much that we know everything. Hence the moments that fall outside Jeff’s range of knowledge in Rear Window, the judicious inserted scene of the agency meeting in North by Northwest, and other instances in which Hitchcock slightly widens our range of knowledge, often in a teasing way. 63 An anonymous reviewer for the London Times caught this strategy in Sabotage: Hitchcock will usually “lay most of his cards on the table.” 63 An anonymous reviewer for the London Times caught this strategy in Sabotage: Hitchcock will usually “lay most of his cards on the table.” 64 64

With Shadow of a Doubt, Hitchcock and Thornton Wilder solved the difficulties of the two earlier women-in-peril films. A freer range of narration allows suspense to build: the opening man-on-the-run episode, confined largely to Uncle Charlie, segues into a section that centers on what Young Charlie suspects and eventually discovers. In accordance with Mitchell Wilson’s anatomy of the suspense plot, she takes the initiative and turns on her tormentor, forcing him to leave town. Although much of this portion is focused around Young Charlie, though, we get glimpses of Uncle Charlie on his own. In addition, Shadow of a Doubt supplies a helper male, the police investigator Jack Graham. Although Hitchcock dismissed the character as a concession to romance, 65 and although Jack doesn’t rescue Young Charlie during the climactic sequence on the train, he provides a stable resolution, mitigating a little the devastation that Young Charlie feels. 65 and although Jack doesn’t rescue Young Charlie during the climactic sequence on the train, he provides a stable resolution, mitigating a little the devastation that Young Charlie feels.

Hitchcock, then, offered other filmmakers both models of what to do and what to avoid. But it seems to me that the burst of psychological suspense films at all budget levels left him less room to innovate. Many variations were emerging; the space was getting crowded. Women-in-peril plots featuring murderous husbands had become commonplace, and they often displayed skilful use of restricted point of view, as in Sorry, Wrong Number (1948). There were even “Hitchcockian” movies avant la lettre: The crime inadvertently witnessed, the premise of Rear Window, was tried out in Lady on a Train (1945), in Shock (1946), and perhaps most vividly in Ted Tetzlaff’s The Window (1949), in which a tenement boy sees a stabbing but can’t convince anyone of it.

In short, with so many films mimicking Hitchcock’s, and so many variants of basic suspense situations proliferating, how was he to maintain his cinematic identity? In Spellbound (1945) he led the way to a burst of talking-cure films. He and Ben Hecht blended his favored woman-in-peril situation with spy intrigue in Notorious (1946), making the helper male into a rival suitor from the start and organizing part of the plot around his range of knowledge. For other projects Hitchcock seemed to strain to find something highly distinctive, either dramatically or technically. A contract-fulfilling job, the courtroom drama The Paradine Case (1948) posed appetizing technical challenges, but Selznick’s interference dominated the results.

It seems to me that the proliferation of suspense films was one cause of Hitchcock’s shift to more outré angles for his projects: increased sexual explicitness (The Paradine Case, Rope), provocative drama of ideas (Lifeboat, Rope), confinement to a single setting (Lifeboat, Rope), long-take shooting (Paradine Case, Rope, Under Capricorn), and duplicitous flashback (Stage Fright). Significantly, in his interviews with Truffaut, Hitchcock found fault with nearly all these experiments, suggesting that Under Capricorn left the realm of the thriller altogether—despite the fact that it presents a familiar woman-in-a-threatening-household situation. Having helped set the terms for thriller storytelling in the 1940s, he was obliged to recalibrate what he could offer in the face of competition. 66 66

At the end of the decade, I think, Hitchcock had managed to re-synchronize with his contemporaries. Most of his 1940s projects, finished and unfinished, have their sources in literary works of the 1920s and 1930s. Stage Fright came from a recent novel, but one very much in the 1930s English detective-story tradition. 67 Strangers on a Train (1950), however, was based on a male-oriented psychological thriller written by one of the women participating in the 1940s burst of suspense fiction. Despite making some compromises in adapting Patricia Highsmith’s original, 67 Strangers on a Train (1950), however, was based on a male-oriented psychological thriller written by one of the women participating in the 1940s burst of suspense fiction. Despite making some compromises in adapting Patricia Highsmith’s original, 68 the master of suspense had allied himself with a writer who typified the new phase of the suspense thriller—a phase that he had done much to foster. 68 the master of suspense had allied himself with a writer who typified the new phase of the suspense thriller—a phase that he had done much to foster. 69 69

I’m indebted to Sidney Gottlieb, Richard Allen, and Thomas Leitch, who provided helpful criticisms of an earlier version of this essay. Thanks also to David Meeker, who provided access to a hard-to-find film.

1 : Mitchell Wilson, “The Suspense Story,” The Writer 60, 1 (January 1947), 15.

2 : Wilson, 16.

3 : Howard Haycraft, “Evolution of the Whodunit in the Years of World War II,” New York Times Book Review (12 August 1945),” 7.

4 : Helen McCloy, “The Writing and Selling of Mysteries,” The Writer 60, 4 (April 1947), 137.

5 : Charlotte Armstrong, “Razzle-Dazzle,” The Writer 66, 1 (January 1953), 3–4.

6 : Freeman Wills Crofts, The 12:30 from Croydon (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1965), 187.

7 : Dorothy L. Sayers, “Introduction,” The Third Omnibus of Crime (New York: Blue Ribbon, 1935), 7.

8 : Agatha Christie, Towards Zero (New York: Pocket Books, 1972; orig. 1944), 12–13.

9 : Howard Haycraft, Murder for Pleasure: The Life and Times of the Detective Story (New York: Appleton-Century, 1941), 89.

10 : Quoted in Haycraft, 90.

11 : François Truffaut, Hitchcock (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1967), 127.

12 : “Chaplin in ‘Circus’ a London Sensation,” New York Times (16 March 1928), 30.

13 : Some of these plays can still be read in acting editions. For a generous overview of them and many others see Amnon Kabatchnik, Blood on the Stage 1925–1950: Milestone Plays of Crime, Mystery, and Detection (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2010).

14 : Quoted in Sean French, Patrick Hamilton: A Life (London: Faber and Faber, 1993), 139.

15 : For example, The State v. Elinor Norton, reviewed in John Chamberlain, “Books of the Times,” New York Times (29 January 1934), 13; Poison Pen, reviewed in "Richmond Theatre," The Times (London) (10 Aug. 1937): 8; “Detective Stories: Death Has a Past,” The Times (London) (6 June 1939), 19.

16 : Boileau-Narcejac, Le roman policier (Paris: Payot, 1964), 150–154.

17 : Charles Morgan, “Mr. Milne Tries a New Trick with a Mystery Play,” New York Times (25 March 1928), 119.

18 : For much of what follows, I’m indebted to LeRoy L. Panek’s acute, entertaining study The Special Branch: The British Spy Novel, 1890-1980 (Bowling Green: Bowling Green University Popular Press, 1981), especially chapters 1–12.

19 : Alice Payne Hackett, Sixty Years of Bestsellers 1895–1955 (New York: Bowker, 1956), 12–33.

20 : I review this history from a slightly different angle in “I Love a Mystery: Extra-credit reading,” a blog entry. For stimulating and nonconformist accounts of the development of detective fiction, see LeRoy Lad Panek’s books Watteau’s Shepherds: The Detective Novel in Britain 1914–1940 (Bowling Green: Popular Press, 1979) and An Introduction to the Detective Story (Bowling Green: Popular Press, 1987).

21 : Janice Radaway, Reading the Romance: Women, Patriarchy, and Popular Literature (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1984), 30–31.

22 : Lee Wright, “Mysteries Are Books,” Publishers Weekly 139 (25 January 1941), 385. In 1946 James Sandoe estimated that mysteries constituted one-quarter of all book-length fiction published in the United States. See “Dagger of the Mind” in The Art of the Mystery Story, ed. Howard Haycraft (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1946), 254. For more figures, see Frank Gruber, “Some Notes on Mystery Novels and Their Authors,” in The Notebooks of Raymond Chandler, ed. Frank Gruber (New York: Ecco Press, 1976), 33–34.

23 : Flyleaf blurb for Mitchell Wilson’s The Panic-Stricken (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1946).

24 : “Radio—General Markets,” The Writer 64, 1 (January 1951), 58.

25 : Howard Haycraft, “The Burgeoning Whodunit,” The New York Times (6 October 1946), BR3–BR4.

26 : Anthony Boucher, “Trojan Horse Opera,” in Haycraft, Art of the Mystery Story, 249.

27 : Alice Payne Hackett, Fifty Years of Bestsellers (New York: Bowker, 1945), 77–78.

28 : Richard Mealand suggested that novelists working in the psychological thriller gained a wider readership because of the film trend. See “Hollywoodunit,” in Haycraft, Art of the Mystery Story, 301–303.

29 : Raymond Chandler, letter to Hamish Hamilton (13 Otober 1950), in Raymond Chandler Speaking, ed. Dorothy Gardiner and Kathrine Sorley Walker (Plainview, NY: Books for Libraries Press, 1971; orig. 1962), 60.

30 : Anonymous, “New Trend in the Horror Pix,” Variety (16 October 1944), 143.

31 : Fred Stanley, “Hollywood Shivers,” New York Times (28 May 1944), X3.

32 “New Trend in the Horror Pix,” 143.

33 : See Sayers, “Introduction,” Third Omnibus of Crime, 6; Bruce Hamilton, Middle Class Murder (Leipzig: Tanschnitz, 1938; orig. 1936).

34 : Hollywood, The Dream Factory: An Anthropologist Looks at the Movie-Makers (Boston: Little, Brown, 1950), 119, 140. See also Stanley, “Hollywood Shivers,” X3.

35 : Howard Haycraft, “Evolution of the Whodunit in the Years of World War II,” New York Times Book Review (12 August 1945),” 7.

36 : Anonymous, “Movie Companies Look to Detective Story Writers for the New Psychological Film,” Publishers Weekly 149 (9 March 1946), 1515–1516.

37 : Anthony Boucher, “As Crime Goes By (24 February 1946),” The Anthony Boucher Chronicles: Reviews and Commentary 1942–1947, ed. Francis M. Nevins (Lexington, KY: Ramble House, 2001), 102.

38 : “New Films in London,” The Times (London), 25 May 1936, 12.

39 : See Tom Ryall, Alfred Hitchcock and the British Cinema (London: Croom Helm, 1986) and Robert Murphy, “Dark Shadows around Pinewood and Ealing,” Film International no. 7 (2004), 28–35.

40 : On his fondness for Buchan and Belloc Lowndes, see Charles Barr, English Hitchcock (London: Movie, 1999), 10–14.

41 : Patrick McGilligan, Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light (New York: HarperCollins, 2003), 212.

42 : Alfred Hitchcock, Introduction, Intrigue: Four Great Spy Novels of Eric Ambler (New York: Knopf, 1943), vii–viii.

43 : “Foreign Correspondent,” Variety (28 August 1940), 16; Philip K. Scheuer, “A Town Called Hollywood,” Los Angeles Times (7 April 1940), C3; advertisement for Rebecca, Variety (24 April 1940), 21; advertisement for Shadow of a Doubt, Variety (19 January 1943), 4; advertisement for Lifeboat and Spellbound, Variety (23 February1945), 12. Supposedly the “master of suspense” label was coined by a New York advertising agent promoting the Suspense radio pilot (McGilligan, Alfred Hitchcock, 276).

44 : “Ladies in Retirement,” Variety (20 March 1940), 50.

45 : “Crossroads,” Variety (24 June 1942), 8.

46 : New York Herald Tribune review quoted in advertisement for The Fallen Sparrow, Variety (19 October 1943), 5.

47 : Philip K. Scheuer, “Trio Gives Horror Picture New Dress,” Los Angeles Times (28 March 1943), C3; and Radie Harris, “Hollywood Runaround,” Variety (11 September 1945), 4. The Disney film Harris mentions is Make Mine Music, in which the Johnny Fedora and Alice Blue Bonnet episode is said to contain suspense “as breathless as a Hitchcock thriller.”

48 : Philip K. Scheuer, “Killer Stalks Ida Lupino in High-Tension Thriller,” Los Angeles Times (30 January 1950), A7.

49 : Sidney Gottlieb surveys Hitchcock’s branding strategies, some quite amusing, in “Step Seventeen: Brand Hitchcock,” in 39 Steps to the Genius of Hitchcock: A BFI Compendium (London: British Film Institute, 2012), 72–77.