The Hook: Scene Transitions in Classical Cinema

January 2008

How do movies carry us from scene to scene? The question is simple, but not

many people have explored it. I’m especially interested in how transitions

are managed in mainstream, mass-audience movies, but I’ll have some things

to say about other traditions too.

I’ll also be talking a lot about unity, which can make the whole exercise

seem fairly old-fashioned and Aristotelian. Yet examining how films create internal

patterns reminds us that those patterns are almost always aimed at the audience.

We’re supposed to register those patterns, consciously or not, and they

prompt us to react in particular ways. As so often, when we talk about form we’re

actually talking about the psychology of spectators.

A movie’s architecture

If we want to know how mainstream movies take us from scene to scene, I suggest

we start by acknowledging three different levels of architecture.

First, we can consider our film as having large-scale

parts. Call this macrostructure—the

way those biggish parts fit together.

We might treat reel lengths as

the salient parts, as silent filmmakers and Hong Kong filmmakers sometimes did.

More recently, we’re urged to think

of the large-scale parts as acts, either three in the current Hollywood

advice books or four, as Kristin Thompson and I have suggested. But these more

or less material divisions tally up with phases of the story action. So, for

example, the traditional conception of three-act structure depends on the main

characters choosing goals, being blocked in achieving them, and at the climax

decisively achieving them or not.

In National Treasure (2004), Benjamin

Gates is searching for the treasure of the Knights Templar. He’s kept from

achieving this goal by conflicts, obstacles, and delays. In the film’s

first part, he and his assistant Riley learn that directions to the treasure

are inscribed on the back of the US Declaration of Independence. But Ben’s

former backer Ian is also on the trail of the map, so our heroes acquire another

goal: to protect the Declaration. At the turning point of the first part, Ben

decides that the only way to achieve his goals is to steal the Declaration. In

the second part, Ben and Riley make off with the document, picking up archivist

Abigail along the way. The third part consists of following the trail of clues

laid out in the coded message, as our three are pursued by Ian’s gang and

by the FBI. The film’s fourth part constitutes

a climax. The trail leads to Manhattan, where Ian takes our heroes hostage and

they plunge into a lair underneath a church. The treasure is discovered, Ian

is defeated, and in an epilogue the protagonists are rewarded.

For more on macrostructure, see the essay, “Anatomy

of the Action Picture” elsewhere

on this site.

At a lower level, we can think of the film as having midsize

parts, usually called scenes or sequences.

These parts, usually 30 to 50 in a modern feature, are tied together in particular

ways. Typically the scenes develop and connect through short-term chains of cause

and effect. Characters formulate specific plans, react to changing circumstances,

gain or lose allies, make appointments, act under deadlines, and otherwise take

specific steps toward or away from their goals. Part of the screenwriter’s

craft is to find ways to fit the short-term actions into the overarching movement

toward resolution.

In National Treasure, for example, the first large-scale part consists

of concrete actions that flow naturally out of the goals. To find the treasure,

Ben and Riley and their opponents need the map. The map is on the Declaration

of Independence. Ian will try to steal it, so Ben tries to alert the FBI, but

he’s considered a crank. He tries to get permission to look at the Declaration,

but that effort fails too. So he is obliged to protect it from Ian by stealing

it himself. This cascade of choices, actions, and reactions flows logically out

of his double goals: to find the treasure and to protect the Declaration.

This second level of structure isn’t quite as linear

as I’ve made

it out, since well-constructed plots interweave various elements from earlier

scenes into the development of later scenes. Appointments and deadlines illustrate

this strategy. So does a causal chain that’s left unresolved in one scene.

Kristin and I have called this device the dangling cause, and it is

very common in Hollywood dramaturgy. For example, in National Treasure,

when calling on Abigail to seek permission to examine the Declaration, Ben notices

a folder advertising an archive reception. Several scenes later we learn that

that reception will be the occasion on which Ben and Riley pull off their heist.

Because of this weaving of causes and effects, we might best call this midlevel

architecture the level of plot coherence: each scene is designed

to advance the action but also to develop or tie off lines of activity set off

earlier.

A third, still finer-grained level of organization is what

I’ll

call microstructure.

This is the tangible, moment-by-moment texture, conceived as a pattern of images

and sounds. For example, within a scene, we often find patterns of cutting—an

establishing shot, reverse angles, close-ups, and so on—meshed with the developing

dialogue. The audiovisual patterning carries the story along bit by bit, and

these bits we take in and assemble into larger patterns of intelligibility, such

as Ben and Riley fail to persuade Abigail to let them study the Declaration.

Likewise, in action sequences, cutting, composition, point of view, sound-image

interaction, and the like carry the discrete developments of the action, which

we intuitively pull into a larger unit, such as Ben, Riley, and Abigail escape

Ian and keep custody of the Declaration.

Global macrostructure, midlevel

plot coherence, and audiovisual texture or microstructure: we can study a film’s

narrative at any of these levels. Usually we hop back and forth among them, searching

for patterns that yield significant effects on the viewer’s experience.

I’ll try to convince you that transitions

play an important role in those patterns.

Meet the Hook

Most scene transitions facilitate the first and second

levels of unity. In many films, a fade-out marks the end a discrete “act.” At

the midrange level of coherence, the end of one scene and the beginning of another

will often be marked in a conventional way, by a disjunctive cut or a burst of

music. Usually, however, the immediate blow-by-blow action of scene A and its

audiovisual texture aren’t linked directly to that of Scene B.

Take an example from National Treasure. Kicked out by the FBI, Riley

says that they have no one to turn to, but Ben says that they need someone who’s “passionate.”

Cut to the exterior of the National Archives building, then a close-up of

the flyer for the gala that will be so important in the second part.

After several more shots, Ben and Riley are ushered in to meet Abigail.

The first part of the scene has left the causal line of the men’s search dangling

in order to wedge in the motif of the reception brochure. Now their hunt for

a helper resumes.

But suppose things were presented differently. Suppose that after Ben says they

need someone passionate, we cut directly to the close-up of Abigail on the phone.

That would be an example of the sort of transition that most interests me in

this essay: The hook.

In our book The Classical Hollywood Cinema, we

called it that, and nowadays some screenwriters use the term too. 1 Here

the audiovisual texture links a specific causal element the end of one scene

to that at the very start of the next. The second, in a concrete way, completes

the element we see or hear at the end of the first scene. 1 Here

the audiovisual texture links a specific causal element the end of one scene

to that at the very start of the next. The second, in a concrete way, completes

the element we see or hear at the end of the first scene.

At a later point in National Treasure, driving away from the scene of

their robbery, Ben mentions the clues in “those letters.” “What

letters?” asks Abigail, over a shot of the van. Cut to an extreme long

shot of the van parked, Ben pacing outside it. Abigail is saying, “You

have the original Constance Dogood letters.”

Scene A ends with a question; scene B opens with the answer.

This is a common way a hook is used, though we’ll see that principles of

continuity or contrast can work as well.

But first, let’s map the possibilities. Confining ourselves for the moment

to sound cinema, we can ask: What can hook to what? There are four simple possibilities.

1.) A sound can hook to another sound. Typically,

a line of dialogue at the end of scene A links directly to a line at the start

of scene B. That’s what happens in the Constance Dogood instance. Here’s

another example from National Treasure. Riley is insisting that the

Declaration is impossible to steal. On the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, he

says, “Let me prove it to you.” Cut to the dome of the Library of

Congress.

At the visual level, this might seem not to be a tight

link; isn’t it

like the exterior shot of the National Archives in the default example? What

creates the hook is the second shot’s use of Riley’s voice, which

says that he has brought Ben to the Library of Congress to convince him to “listen

to Riley.” This is the proof he proffered in his final line of the previous

scene.

So this first type of hook is easy to test for. Just ask: Would it work on radio?

2.) A sound can hook to an image. Usually

the sound is a line of dialogue. In CHC, we called this a “dialogue

hook.” Lewis

Herman, in his indispensable book on screenwriting, calls it a “dialogue

transition.” 2 2

This is the most common sort of hook in National Treasure, and it provides

some clever transitions. When Ben and Abigail are trying to bring out the cipher

on the back of the Declaration, they squeeze on lemon juice and blow fervently

on the paper. The image clarifies.

Ben: “We need more juice.” Abigail: “We

need more heat.”

Cut to a bowl of lemons, then to a drawer opening to reveal a hair dryer.

Ben and Abigail proceed to coax the code out of the paper.

This is a double dialogue hook, “juice” answered by the lemons

and “heat” answered by the dryer. The double entendre adds a nice

twist, for the scene captures the erotic energy—juice and heat—Ben

and Abigail share in making a historical discovery.

3.) An image can hook to an image. This

is rarer than the first two types, but the first hook in National Treasure illustrates

the possibility. In the prologue, as a boy Ben learns of the Templars’ treasure

from his grandfather. Grandpa Gates asks him to take on the duty of protecting

the treasure and the family name. “I so swear.” The young Ben raises

his head as the music starts to rise as well.

Cut to Ben, now a man, raising his head as he and Ian drive across the arctic

wastes to find the buried ship, the Charlotte.

The match-on-action across years is driven home by a rhythmic shift in the

score and a new, urgent brass theme.

The image-based hook is somewhat more common in the 1920s and 1930s, I think.

Ozu uses it a lot, and here is an example from Fritz Lang’s You Only

Live Once (1937). We dissolve from a cluster of parcels in an office to

the same parcels, now opened at home.

Lang, as we’ll see below, is one of the early masters

of the hook.

4.) An image can hook to a sound. This seems to be the rarest

sort of audiovisual transition, and pure examples are hard to find. Imagine a

shot of a commander signing an order for a prisoner to be shot by a firing squad.

Cut to darkness and the sound of a fusillade; fade up to show the prisoner lying

dead against the wall.

I don’t find an instance in National Treasure, but Kristin suggests

one example from Groundhog Day. Phil the weatherman has already been

through one day’s repetition of events. He tests whether tomorrow will

be the same by breaking a pencil and putting the pieces on his bedside table.

He lies there propped up and watching the digital clock face. He evidently intends

to stay up all night to see what happens around six o’clock.

Cut to an extreme close-up of the clock face changing to

6:00 and the tune, “I’ve

Got You Babe.” Cut to Phil, who has fallen asleep, snapping bolt upright.

Although the shot of the clock indicates a new scene, the

basic logic of the transition moves us from an image posing a question to a crucial

sound that answers the question. After all, 6:00 AM comes every day, but “I’ve Got You

Babe” doesn’t, thankfully. Director Harold Ramis could just as easily

have cut to a black frame and simply let us hear the tune, and we’d know

that Phil’s fears are now confirmed. Interestingly, we don’t see

the pencil at first; it’s the sound that tells us that the day is repeated,

and the restored pencil confirms it.

Playing games and finding functions

This catalogue is merely a first effort to pick out the possibilities. But we

need to recognize that the hook need not be literal or on the nose. It can be

ironic or nugatory, metaphorical or misleading. We find a deflationary negative

hook in one episode of The Simpsons. Homer: “I predict that this

is the last we’ll be hearing about prohibition.” Cut to enraged women

chanting: “We want prohibition!”

National Treasure creates a playful narration

by means of some misleading hooks. Riley is parked outside the National Archives,

checking on some video installations he’s made that will monitor Ben’s theft. When he finds

they work, he says, “Game on.”

Cut to a digital readout counting down from 3 to End.

A timer in his equipment? Nope; a microwave oven in which Ben is preparing

lasagna before he settles down to studying plans.

What we took as a continuity cut within a scene was a hook

between scenes. A similar effect arises in a transition from Donnie Brasco,

pointed out by Jeff Smith. Lefty is headed out of his apartment, knowing he’ll

be killed. Cut to a black frame.

Over the black frame we hear a gunshot. Cut to a target

on a shooting range, then to Donnie firing.

It’s a rare case of an image/sound hook, but it’s

made ambiguous by the two ways we can take the pistol shot. The sound of the

shot indicates Lefty’s death, although it is retrospectively linked to

the firing range (it sounds the same as the other rounds Donnie fires). Metaphorically,

of course, it underscores the fact that Donnie is responsible for Lefty’s

death.

And hooks can be combined and embedded. We’ve already seen one instance

in National Treasure, the double hook on juice and heat. Here’s

another from the same movie. Sadusky, the FBI officer, is questioning Ben’s

father and assures him, “Don’t worry, Mr. Gates. We’ll find

your car—and your son.”

Cut to the Cadillac hood ornament, and tilt up to show Ben driving.

The two dialogue elements, car and son, have been linked

to the visual ones, and in that order. With the redundancy characteristic of

Hollywood, Riley, dozing in the back seat, murmurs, “Your dad’s got

a sweet ride.”

We’ll consider some other complicated cases later, but we should have enough

examples to begin to ask about functions. What purposes are fulfilled by the

hook? Why should we have the hook at all?

Lang, who used sound/sound hooks extensively in M (1931),

explained two reasons behind his choice. First, breaking off a line and completing

it with another in the next scene “not only accelerates the tempo of the

film but also strengthens the dramaturgically necessary association of thoughts

between two successive scenes.” 3

So we gain pacing, an impression of rapid narration, as if there were no time

wasted on establishing shots and other padding. We also gain emphasis: the core

motifs of a scene can be brought directly to the viewer’s

attention. In many cases, however, this second condition isn’t met; in

many of the National Treasure examples, the hooking elements are peripheral

to the scene (the lasagna, the Cadillac). 3

So we gain pacing, an impression of rapid narration, as if there were no time

wasted on establishing shots and other padding. We also gain emphasis: the core

motifs of a scene can be brought directly to the viewer’s

attention. In many cases, however, this second condition isn’t met; in

many of the National Treasure examples, the hooking elements are peripheral

to the scene (the lasagna, the Cadillac).

An implication of Lang’s point

is that hooks create a more overt narration. They address the audience more or

less directly, letting us put the scenes together without benefit of character

exposition. This sort of direct address can work in classical films because the

beginnings and endings of scenes are typically the most overt portions. (Some

theorists have claimed that Hollywood storytelling is “transparent,” but

this quality actually fluctuates across the film and across individual scenes.)

This overt narration can build up a sense of cleverness or resourcefulness or

sophistication.

In some of the more complex cases, the hook also functions

as useful disorientation. It provides a bump, asking us to be alert and find

a fresh way to fit together what was just said or shown.

One of the most interesting

functions of the hook is that the strong audiovisual cohesion it yields can give

the impression of a tightly unified film. This could be valuable in the case

of a movie that lacked plot coherence or a balanced macrostructure. That is,

clever hooks can mask a weakly plotted movie. You might argue that the strong

local connections among scenes in National Treasure distract

us from the massive improbabilities of the action.

Most rarely, I think, reliance

on hook-transitions can feed into a larger strategy of narrational manipulation.

The key example would be, again, You Only Live

Once. I must speak generally so as not to spoil the film if you haven’t

seen it. Here the hooks are part of a larger system of ellipses between scenes.

At first those ellipses don’t conceal important story information, but

at a crucial point they do. Lang trains us to see the hooks as innocent, if flamboyant,

gestures, but in fact they lull us into trusting this narration, which brutally

betrays us.

The hook in history

Where, finally, did

the hook come from?

We can find it in literature, although exact analogies

are complicated. Certainly hooks are common in today’s popular fiction; I append

some examples at the end of this essay. But did the device originate in the nineteenth-century

novel? I leave that for literary researchers to determine.

In cinema, it’s clearly a device of classical filmmaking. It flourished

in the 1930s, not only in You Only Live Once but in Penthouse (1933)

and The Case of the Lucky Legs (1935; discussed in The Classical

Hollywood Cinema). It can be seen in Hitchcock’s The Man Who Knew

Too Much (1934) as well, and of course Welles makes much of hook tactics

in what he called the “lightning mixes” of Citizen Kane (1941).

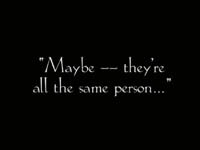

How far back can we trace it? Noël Burch argues that

Lang in effect invents the hook in Dr. Mabuse der Spieler (1922), especially

in the way that intertitles work with the images that precede and follow them. 4 When

the police inspector von Wenk speculates that all the mysterious men might be

the same person, we cut to Mabuse in his laboratory; the shot confirms von Wenk’s

hypothesis. 4 When

the police inspector von Wenk speculates that all the mysterious men might be

the same person, we cut to Mabuse in his laboratory; the shot confirms von Wenk’s

hypothesis.

But we ought to note that the “hooking” transitions

in Mabuse tend

to occur not between scenes but between two crosscut threads of a single long

sequence. Silent films were typically built out of long sequences, often crosscut

ones that trace parallel lines of action. When talkies came in, sequences grew

shorter and more numerous, and crosscutting was chiefly assigned to situations

of suspense.

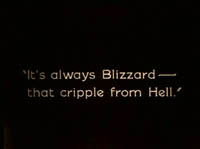

In any case, before Mabuse, other films were using

the sort of hooks that Lang did. For instance, in The Penalty (1920),

the cops discuss Blizzard, the gangster played by Lon Chaney, and the dialogue

hooks are aligned with shots identifying him.

Other examples can be found in The Whispering Chorus (1919)

and A

Delicious Little Devil (1919). Granted, these passages are not quite as

crisp and curt as Lang’s juxtapositions, but they might be considered intermediate

steps toward what Lang would do. In the Penalty passage, it isn’t

difficult to see that you could cut straight from the dialogue title to a close

shot of Blizzard interrogating his minion. Changes in stylistic history can arise

from tightening up a schema, making it less redundant.

Lang applied the tighter

version to M, and it’s likely that that

film was influential in popularizing these practices for Hollywood in the 1930s.

Filmmakers of the sound era started to take audiovisual texture very seriously,

and as scenes became shorter, cohesion tactics became more valuable. Hooks are

today written into the script, even if they aren’t used or are replaced

by different ones. 5 A

remark of Elmore Leonard’s about writing screenplays confirms the importance

of transitions in modern cinema. “I like to add scenes, but then when it

comes to the transitions you’re in big trouble. You can’t just stick

a scene in because you feel like it.” 5 A

remark of Elmore Leonard’s about writing screenplays confirms the importance

of transitions in modern cinema. “I like to add scenes, but then when it

comes to the transitions you’re in big trouble. You can’t just stick

a scene in because you feel like it.” 6 6

Revising the schema

Because the hook is a classical device, we might be inclined to expect that other

traditions don’t make use of it. This belief isn’t wholly wrong.

Maurice Pialat asked a would-be editor: “Do you like films in which the

guy says, ‘Let’s go to the sea,’ and the next scene is on the

seashore?” 7 7

It isn’t hard to find films outside the mainstream

that deny us such hooks. A notable example is Michael Haneke’s 71 Fragments

of a Chronology of Chance (1994), in which each scene is separated off from

the others by black leader and silence, refusing the forward tug of the action.

But more interestingly, we find that “art movies” use hooks too.

Bresson does it in an effort to be laconic. At the beginning of Au hasard

Balthazar (1966), Marie’s

father refuses to buy the donkey, but in the next shot we see him leading it

off. Hooks can also be comic, as in Tsai Ming-liang’s What Time Is

It There? (2001). What we get is a process not of simple refusal but of

borrowing and transformation, schema and revision. A lot of art cinema takes

Hollywood devices and repurposes them.

This isn’t to say that classically constructed films don’t revise

their inherited devices too. This can sometimes occur in those virtuoso moments

so beloved of contemporary Hollywood. One last time, consider National Treasure.

Ben, Riley, and Abigail are in a mall shop when they realize

the import of a clue issuing from the Declaration. It steers them to the clock

tower on Independence Hall, which is represented on the hundred-dollar bill.

Ben realizes that the clock and the time indicated on it point to the next clue

in the hunt. But today, they believe, the appointed hour has passed. But Riley

reminds them that daylight savings time began after the revolutionary period,

so as per the clue’s dictates, they have an extra hour today. The couple rush

off and call out the name of the man who first suggested daylight savings time: “Benjamin

Franklin!” Cut

to Ian, offering a hundred-dollar bill to the little boy who had helped Riley

crack the clue leading to Independence Hall.

In a movie that relies so heavily

on hooks, this transition intertwines them in felicitous ways. The mall scene

ends with Ben and Abigail calling out Franklin’s name. This is an oblique sound/

image hook to the second shot in the following scene, when a reverse angle picks

up the bill and Franklin’s portrait on it.

It’s not irrelevant that our hero’s full name is Benjamin

Franklin Gates.

Even more subtly, earlier in the first scene, Ben’s optical

point-of-view shot underscored the clock motif as he began to understand the

clue. (The framing of Ben and the bill will be mirrored by a reverse shot of

Ian, his adversary.)

The clock motif is picked up in the initial shot of the

following scene, as the little boy examines the bill.

But Ian is blind to the significance of the

clock that is literally staring him in the face. He will soon have to resort

to the duffer historian’s tool, a Yahoo! search.

As a storytelling device, the

hook affects both narrative design and stylistic patterning. Studying it helps

us grasp some basic mechanics of classical storytelling. Just as important, these

devices display tacit knowledge and decisions on the part of filmmakers, who

adapt traditions to the needs at hand. And filmmakers’ tacit

knowledge corresponds to that of audiences, the skills you and I exercise unawares.

We can follow the corrugations of sound/ image organization because we know about

the world outside cinema, we know how conventions reshape that world, and we’re

alert for narrative and audiovisual organization. Analyzing how movies are put

together helps us understand how we experience them.

Appendix: The hook in literary texts

George Pelecanos, The Night Gardener (New

York: Little, Brown, 2006). Scene change within Chapter

Twenty-Five, p. 231:

“Let’s

get a beer or something,” said Holiday.

“Drop

me at my car,” said Ramone.

“C’mon,

Ramone. How often do we see each other? Right?”

“I’ll

have a beer,” said Cook.

Ramone looked

over the bench at Cook. He seemed small, leaning against the door in the front

seat of the car.

“Okay,” said

Ramone. “One beer.”

Ramone

was finishing his third beer as Holiday returned from the bar with three more

and some shots of something on a tray.

Elmore Leonard, Unknown Man #89 (New

York: Harper, 2002). End of Chapter 12, p. 144:

Ryan saw the

manager. The manager said he had just talked to the police. Who was this girl,

anyway? What’d she do? She certainly hadn’t worked for Uncle Ben.

Maybe

not, but for some reason she had used the address. She was around, somewhere.

That

was on a Monday.

Chapter 13[p. 145]:

Wednesday

afternoon, Ryan was sitting in a bar on Saginaw Street in Pontiac.

Ian Rankin, The Naming of the Dead (New

York: Little, Brown, 2007). Scene change within Chapter 3, p. 62:

Rebus finished the call, decided to check for messages. There was only the one.

Steelforth’s voice had gotten just a dozen words out before Rebus cut it

off. The unfinished threat echoed in his head as he crossed to the stereo and

filled the room with the Groundhogs.

Don’t

ever try to outsmart me, Rebus, or I’ll…

“…break

most of the major bones,” Professor Gates was saying.

He gave a shrug. “Fall like that, what else can you expect?”

1 : Karl

Iglesias, “8 Ways to Hook the Reader,” Creative Screenwriting 13,

4 (2006), 48–49.

2 : Lewis

Herman, A Practical Manual of Screen Playwriting for Theater and

Television Films (New York: New American Library, 1974; orig. 1952), 134–152.

3 : “Fritz

Lang on M: An Interview,” Criterion DVD

booklet for M (1998), trans. from Gero Gandert interview in Fritz

Lang: M-Protokoll (Hamburg: Marion von Schroeder, 1963).

4 : Burch

discusses these matters in several places. See “Fritz

Lang: German Period,” In

and Out of Synch: The awakening of a Ciné-Dreamer (Aldershot,

England: Scolar, 1991), 3–31; “Notes on Fritz Lang’s first Mabuse,” In

and Out of Synch, 205–227; and “De ‘Mabuse’ à ‘M’:

Le travail de Fritz Lang,” in Cinéma: Théories, lectures,

ed. Dominique Noguez (Paris: Klincksieck, 1973), 227–248.

5 : A late

script draft of National

Treasure, dated

9 April 2003 by Cormac and Marianne Wibberley, includes some intriguing hooks

that were not used in the final film.

6 : Quoted in Woody Haut, Heartbreak

and Vine: The Fate of Hardboiled Writers in Hollywood (London:

Serpent’s Tail, 2002), 224.

7 : Yann Dedet, quoted in

Roger Crittenden, Fine

Cuts: The Art of European Film Editing (Boston: Focal Press, 2006), 26. |