Common Sense + Film Theory = Common-Sense Film Theory?

May 2011

Start with this question, which I think is one of the

most fascinating we can ask: What enables us to understand films?

All films?

Well, set aside some hard cases, like Brakhage abstractions and transmissions

of the Crab Nebula from the Hubble telescope (above). Let’s

start with a prototype: a film whose moving images present more or less recognizable

persons, places, and things caught up in what we intuitively call stories. In

other words, an ordinary movie shown in theatres and on video.

Catching a code

The Naked City.

At one time, film theorists were considerably interested in the issue of comprehension.

The heyday of film semiology, roughly from the mid-1960s to the end of the 1970s,

brought forth vigorous conjectures about how we grasp images and comprehend stories.

One of the boldest proposals was the idea that understanding rests upon codes—rule-governed

relations between the signifier (a material thing, like an image) and a signified

(a concept). In other words, a shot of a cat not only picked out a particular

cat but signified the concept cat. Likewise, we understand a chase scene because

we know the cinematic code for this concept. In Naked City,

we see alternating shots of two men running, and we decode the whole scene as

showing a man pursued and his pursuer.

Semiology was a promising attempt to study

comprehension in a systematic way. This school of thought called our attention

to the ways in which mainstream films are highly structured for audience pickup.

Everything we understand in a movie could be taken as the result of our deciphering codes,

governed by rules and presenting a coherent menu of alternatives. 1 1

For some thinkers, the concept of codes promised to give substance to the age-old “film

grammar” metaphor. Despite some crucial differences, maybe film was really

a sort of audiovisual language, with its own syntax. And since verbal languages

vary dramatically across societies, so might the codes of picturing or of storytelling.

Just as language must be learned, so too perhaps the codes of cinema require

learning.

Semiological research reminded us that what seems natural is often very artificial,

and relative to one society rather than another. In another culture, the code

of traffic signals might employ not red, yellow, and green lights, but any other

colors. The notion of codes also suited an emerging view of what one influential

book of the time called the “social construction of reality.” 2 Would

people from cultures without cinema or television be able to recognize the blobs

on the screen as people and settings? Do codes go all the way down to the very

core of our perception? At some point someone was sure to bring up the idea that

Eskimos had six or ten or thirty different words for what Americans just called “snow.” 2 Would

people from cultures without cinema or television be able to recognize the blobs

on the screen as people and settings? Do codes go all the way down to the very

core of our perception? At some point someone was sure to bring up the idea that

Eskimos had six or ten or thirty different words for what Americans just called “snow.” 3 3

Today, classic semiologists are rare in film studies.

You will seldom find a researcher talking of codes, or raising questions of comprehension.

Nevertheless the idea that filmic expression is quite arbitrary, socially constructed,

and learned remains in the ether. Film academics assume, along with most humanists,

that once you set aside some uninteresting aspects of the human creature, usually

summed up as “physiology,” culture goes all the way down. Beyond

cell division and digestion, let’s say, everything is cultural, and to

invoke any other explanations risks rejection.

That 80s show

In Narration in the Fiction Film (1985), I asked

how we could best explain our grasp of one aspect of cinema, the flow of story

information I called narration. I argued that since most narrative films were

made in order to be experienced by viewers, we ought to study the strategies

filmmakers used to elicit understanding. Most of those strategies, it seemed

to me, exploited rather general human perceptual and cognitive capacities.

Perceptual

research of the 1970s was dominated by a school of thought derived ultimately

from the great psychophysicist Helmholtz. “New Look” perceptual

psychologists like Jerome Bruner and Richard Gregory held that the stimuli hitting

our sense organs were noisy, incomplete, and ambiguous; we needed higher-level

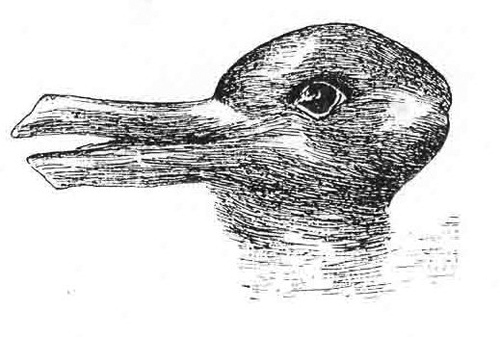

faculties to sort them out. Illusions like the famous duck/ rabbit showed that

when we could not decide between one visual configuration and another, endless

ambiguity was the result. The eye, as was commonly said, was part of the mind.

Seeing in the full sense was a kind of inference to the best explanation: What

could be out there that would produce this pattern on the retina?

At first, this

research tradition meshed neatly with the emerging discipline of cognitive science.

In the early 1980s, cognitive scientists were largely focused on matters of language,

reasoning, applying categories, and making decisions about action. 4 As

with New Look thinking, cognitive science saw mental activity as a quasi-Kantian

interplay of input stimuli and conceptual structures, sometimes called schemas,

that made sense of the data. Those structures might be all-purpose or specialized,

diffuse (like, say, the ability to solve problems) or single-purpose (the ability

to recognize faces). Again, inference was the model, although some mental inferences,

like those involved in vision, were held to be fast, automatic, and “informationally

encapsulated” (i.e., ignorant of anything outside their dedicated domain). 4 As

with New Look thinking, cognitive science saw mental activity as a quasi-Kantian

interplay of input stimuli and conceptual structures, sometimes called schemas,

that made sense of the data. Those structures might be all-purpose or specialized,

diffuse (like, say, the ability to solve problems) or single-purpose (the ability

to recognize faces). Again, inference was the model, although some mental inferences,

like those involved in vision, were held to be fast, automatic, and “informationally

encapsulated” (i.e., ignorant of anything outside their dedicated domain). 5 Eventually,

the inferential approach would become the basis of a computational approach to

both perception and cognition, and it probably remains the dominant view in psychological

research. 5 Eventually,

the inferential approach would become the basis of a computational approach to

both perception and cognition, and it probably remains the dominant view in psychological

research.

How adequate were New Look perceptual theory and Cog Sci mental mechanics to

explaining everyday thinking? NiFF tried to be somewhat agnostic on

certain points, but it did argue that these psychological frames of reference

were helpful in studying films. Perceptually, films are illusions, not reality;

cognitively, they are not the blooming, buzzing confusion of life but rather

simplified ensembles of elements, designed to be understood. They are made to

engage thought, particularly thought that goes “beyond the information

given.” 6 Film

narratives, like narratives in all media, abstract and streamline their real-world

components for smooth pickup and invite us to fill in what is left unshown and

unsaid. What outline drawings are to the eye, narratives are to the mind. 6 Film

narratives, like narratives in all media, abstract and streamline their real-world

components for smooth pickup and invite us to fill in what is left unshown and

unsaid. What outline drawings are to the eye, narratives are to the mind.

So NiFF claimed that we could study films as

ensembles of cues that prompt inferential extrapolation at many levels—of

perception, of comprehension, and of interpretation. In other words, films prompt

us to apply schemas, or

knowledge structures, to what we see moment by moment on the screen. Those schemas

can be based in real-world knowledge or filmic conventions. Each type posed problems

for the concept of codes.

Real-world knowledge may not be as strictly structured

as the concept of code suggests. A schema is less rigid than the traditional

concept of code; it may not exist as binary alternatives or rule-governed choices.

Some schemas are fuzzy, with their members conceived as prototypes or core/periphery

structures. So for us a robin is a prototypical bird, a penguin or ostrich is

not. The latter might be prototypes for people in other cultures, but that doesn’t

invalidate the point that some categories are organized by “best-instance” criteria

rather than hard and fast boundaries.

Some cinematic conventions more crisply

structured: You can end a scene with a cut or a fade or a dissolve or a wipe

or a swish-pan….and that’s

about it. So sometimes we encounter, particularly within certain cinematic traditions,

a sort of menu of options we might call a code. But a lot of conventions, like

those indicating the overall space of a scene’s action, are looser. There

is no rule that requires a long-shot to be followed by a close-up, the way a

preposition in language requires an object. There is no code that dictates that

a sexy scene must be red-tinted or accompanied by hazy saxophone music, but when

such cues emerge, we make a probabilistic inference that seduction isn’t

far off. Not all conventions, it seems, are coded. NiFF studied several of these

conventions under the rubrics of causality, time, and space. Those three categories,

NiFF claimed, are basic to narrative and to human cognition, and so they ought

to play roles in the process by which we understand stories.

Further, NiFF argued

that the conventions that guide our inferential extrapolation don’t simply

float free in space. There were recurring clusters of favored choices for presenting

causality, time, and space. These modes included “classical” narration, “art-cinema” narration,

and others. The historical layout still seems valid to me, and they seem to have

proven useful to other researchers.

Theoretically, however, NiFF ran into problems in the role it assigned

to inference. At the time of writing NiFF, I was aware of the writings

of J. J. Gibson and his insistence that perception evolved in environments very

different from the impoverished information that New Look theorists assumed triggered

perception. In the three-dimensional world in which creatures like us live, the

stimuli are not typically partial or degraded; they are in fact quite rich, even

redundant. Moving through space, we register an optic flow that specifies the

layout of surfaces quite precisely. 7 7

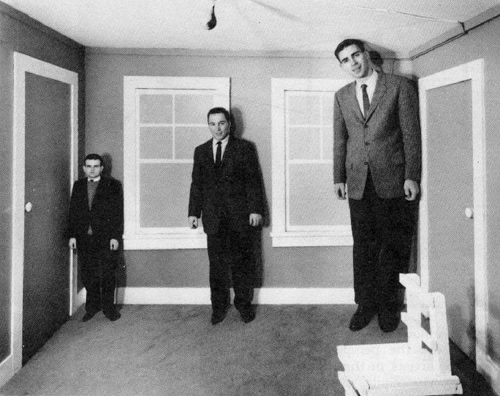

NiFF finessed this problem by saying that even if Gibson’s account

of ordinary perception were right, films don’t present the informational

array afforded by the real world. Film images—flat, often in black-and-white—are

in principle as ambiguous as the duck/rabbit. I invoked the splendid Ames Room

as evidence that, being monocular, cinema images were inherently ambiguous. 8 8

This now seems to me misguided. Films, as Gibson himself

pointed out, disambiguate their images to a huge extent by the sheer fact of

movement. It would take a mental effort no one could summon up to see alternative

ways to construe a normal shot of three men in a room. My mistake was the same as

the New Look theorists: I picked the wrong prototype. Just as illusions aren’t

fair samples of perception in the wild, so the Ames Room is an extraordinary

piece of filmmaking artifice, not a typical one. My old friends Barb and Joe

Anderson were right: Gibson has the best of this argument. 9 (That

still won’t settle whether the inferential/computational approach or the

ecological approach is the better explanation of natural vision. On that I retreat

to the amateur’s agnosticism.) 9 (That

still won’t settle whether the inferential/computational approach or the

ecological approach is the better explanation of natural vision. On that I retreat

to the amateur’s agnosticism.)

I was on surer ground, I think, in treating narrative comprehension as a version

of inference-making. But NiFF pushed it in a problematic direction.

Considering narrative comprehension as inferential led me to bring in the Russian

Formalist distinction between fabula and syuzhet. These two

terms have been used in several ways, but the most plausible way, it seemed to

me then and seems still, is to see fabula as the chronological-causal

string of events that may be presented by the syuzhet, the configuration

of events in the narrative text as we have it.

Clearly the distinction is useful as an analytical tool, to study how a narrative

can “deform” its underlying story for aesthetic purposes. But NiFF went

beyond treating the distinction as purely a tool for analysis. It argued that

it was psychologically real; that as we encountered events in the syuzhet,

we were tacitly building up the fabula too. The process is a bit like double-entry

bookkeeping, with the viewer keeping track not only of what is happening each

moment on the screen but also slotting that into the chronological pattern of fabula events.

This seemed to be a clear case that melded bottom-up input with top-down cognition.

Unfortunately, some people argued, it’s psychologically implausible. Eventually

I had to agree. For one thing, we aren’t aware of building up a fabula in

our heads, the way we can be at least partially aware of, say, solving a crossword

puzzle. For another, we can’t access it easily; try stopping a film on

video and reciting the entire chain of events leading up to the moment of pause.

Worse, try at the end of the movie to grasp mentally the entire fabula you’ve

purportedly worked out. Chances are you can’t do it. Given that our memories

are reconstructive rather than photographic, creating an accurate fabula is

extremely difficult. More theoretically, Julian Hochberg and Virginia Brooks

proposed some reasons that the viewer’s mental representation for the most

part cannot reflect the underlying structure of the film. 10 10

I think that NiFF made the valid point that our

understanding of narrative is often inferential, and we do flesh out what we’re

given. But I now think that the inference-making takes place in a very narrow

window of time, and it leaves few tangible traces. What is built up in our memory

as we move through a film is something more approximate, more idiosyncratic,

more distorted by strong moments, and more subject to error than the fabula that

the analyst can draw up. Indeed, the real constraints on what we can recall make

deceptive narration like that in Mildred Pierce and other films possible. 11 11

Still,

I think the error was a productive one. In assigning to the spectator the task

of ongoing fabula construction, NiFF harmonized with

one premise I consider central: a holistic sense of form. Even if we scan the

entire narrative through a narrow slit, it’s important for the analyst

and theorist to consider the overall design of the work, the more or less coherent

principles that govern the unfolding tale. I’m thinking of such matters

as smoothly cascading character goals, psychological motives and personality

change, gradual development of knowledge, shifts in viewpoint, repeated and varied

motifs, and finer-grained patterns of visual and sonic presentation. In an analysis

of Jerry Maguire, for instance, I tried to show how such features were

operating at many scales, creating a considerable formal richness. 12 12

Such design features need to be accounted for, especially

when they crop up in an otherwise innocuous popular movie. Why are many movies

more tightly organized than they need to be, given the drastic limits on viewer

attention and memory? Clearly, goals, motifs, and the rest aim to shape the spectator’s

experience in some respect, and we may well register many of them at some level

of awareness. NiFF posited

a too-sapient viewer, but methodologically at least, it’s better to point

up many things that a spectator could respond to, even if no real spectator

grasps or recalls all of them. Indeed, some narrative traditions seem to try

to pack things tightly, so that readers or viewers can return to the book or

film and notice things that escaped them on a first pass. Here, as elsewhere, NiFF’s

desire to mix formal analysis with an account of spectator response created some

gaps in the theory, but in some respects it’s better to have more to explain

(about the architecture and detail of the film) than less. It’s a dynamic

I’m still trying to refine many years later.

For the most part, NiFF explicitly

left aside the emotional dimensions of narration. That was done on the assumption

that comprehension as such was relatively insulated from affective response.

You can follow a story, I claimed, without being moved by it. This emphasis was

again consistent with mainstream 1970s and 1980s cognitive science; the index

of Martin Gardner’s 1985 survey,

The Mind’s New Science, contains no entry for “emotion.” And

I did consider what we might call some “cognitive emotions”: curiosity,

suspense, and surprise, all called up by the process of narration. In the decades

since the book was written, however, the relation of emotion to cognition has

become central to cognitive science, and it has been explored by several film

scholars working in the cognitivist paradigm. 13 It’s

still not something I focus on, but it’s obviously of great importance. 13 It’s

still not something I focus on, but it’s obviously of great importance.

Finally,

someone might ask: Why contrast NiFF’s cognitive approach

with semiology, which was passing out of favor when the book was written? Surely

the dominant approaches emerging in the 80’s were neo-Marxism, psychoanalysis,

cultural studies, and the study of modernity and postmodernity.

Here’s my

answer. These perspectives don’t play a role in NiFF,

or in this essay, because their proponents weren’t asking about how films

are understood. These writers focused on questions of how social, cultural, and

psychodynamic processes were represented in films. Typically those questions

were answered by interpreting individual films, reading them for traces of the

larger processes made salient by the given theory.  14 My

concern was explaining, not explicating; I wanted functional and causal-historical

accounts of why films in various traditions displayed certain regularities in

their narrational strategies. That was, I thought, most pertinent to the semiological

line of inquiry. 14 My

concern was explaining, not explicating; I wanted functional and causal-historical

accounts of why films in various traditions displayed certain regularities in

their narrational strategies. That was, I thought, most pertinent to the semiological

line of inquiry.

In the period since NiFF was published, cognitive

film studies has moved in parallel with cognitive science generally. We have

had neurological studies of film viewing; we have seen appeals to evolutionary

psychology; we have seen studies of suprapersonal patterns of emergence. 15 These

all seem to me fruitful. In what follows, I want to sketch out some ideas that

I’d develop in a new and improved version of NiFF. These bear

on our perception of images, on folk psychology, and on social intelligence.

All of these have been developed, at least a little, in work I’ve done

in more recent years. 15 These

all seem to me fruitful. In what follows, I want to sketch out some ideas that

I’d develop in a new and improved version of NiFF. These bear

on our perception of images, on folk psychology, and on social intelligence.

All of these have been developed, at least a little, in work I’ve done

in more recent years.

Dog!

We speak of “reading” an image, but do certain

kinds of images—those

that common sense declares “realistic”—demand anything like

the deciphering that printed language does? How much does grasping an image depend

on learned conventions of representation?

In NiFF I waffled on the question

too much. Although I accepting that some aspects of image perception rode on

skills acquired in commerce with the world, I granted some role to learning and

familiarity with a “carpentered

world.” More subtle is Paul Messaris’s admirable Visual Literacy:

Image, Mind, and Reality (1994). Messaris reviews the anthropological and

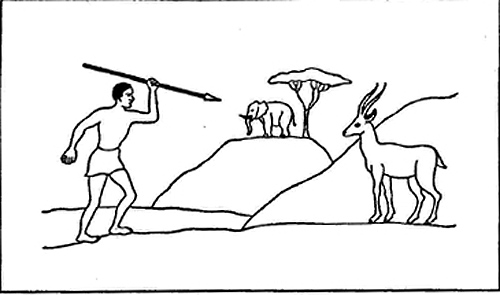

psychological literature in a very clear fashion. He points out that some conventions

for representing depth in still images may not be widely understandable; the

classic example is the drawing above, which was interpreted by viewers in some

African cultures as a hunter pointing his spear at a very tiny elephant. 16 This

suggested that some pictorial depth cues require repeated exposure or training.

But when it comes to recognizing objects that viewers know from everyday

experience, there is no problem. The African viewers recognized the tiny elephant as an

elephant. 16 This

suggested that some pictorial depth cues require repeated exposure or training.

But when it comes to recognizing objects that viewers know from everyday

experience, there is no problem. The African viewers recognized the tiny elephant as an

elephant.

When it comes to moving pictures, the issue is even clearer.

Messaris finds no evidence that people previously unacquainted with movies fail

to grasp the persons, places, and things shown on the screen. This is congruent

with more recent research by Stephan Schwan and Sermin Ildirar, who studied adult

viewers’ first

experience of watching films.  17 Indeed,

all three researchers offer evidence that even some editing techniques are immediately

understood by first-time viewers. 17 Indeed,

all three researchers offer evidence that even some editing techniques are immediately

understood by first-time viewers.

On the “film as language” question Messaris’s conclusions

are clear:

What distinguishes images (including motion pictures) from language and

from other modes of communication is the fact that images reproduce many of the

informational cues that people make us of in their perception of physical and

social reality. Our ability to infer what is represented in an image is based

largely on this property, rather than on familiarity with arbitrary conventions

(whereas the latter play a primary role in the interpretation of language, mathematics,

and so on). 18 18

Messaris’s review suggests that grasping pictures rides on our abilities

to identify objects and spatial layouts in the real world. Some intriguing research

on infants reinforces the point.

In a famous experiment, Julian Hochberg and Virginia Brooks kept their son away

from pictures during his first eighteen months. He did occasionally see billboards

and a few picture books and labels, but when a picture was encountered, the parents

never pointed out its contents or tried to name them. At nineteen months, when

the boy was starting to spontaneously call out names of things he spotted in

accidental images, “It was evident that some form of parental response

to such identification would soon become unavoidable.” In a series of tests

the boy was shown line drawings and pictures of dolls, shoes, toy trucks, keys,

and other familiar objects. He named them to a high degree of accuracy. Hochberg

and Brooks concluded:

It seems clear from the results

that at least one human child is capable of recognizing pictorial representations

of solid objects (including bare outline drawings) without specific training

or instruction. This ability necessarily includes a certain amount of what we

normally expect to occur in the way of figure-ground separation and contour formation.

At the very least, we must infer that there is an unlearned propensity to respond

to certain formal features of lines-on-paper in the same way as one has learned

to respond to the same features when displayed by the edges of surfaces….

The complete absence of instruction in the present case…points

to some irreducible minimum of native ability for pictorial recognition. If it

is true also that there are cultures in which this ability is absent, such deficiency

will require special explanation; we cannot assert that it is simply a matter

of having not yet learned the “language of pictures.” 19 19

Hochberg and Brooks used only still pictures, although

their son did once glimpse a horse on TV. (He cried, “Dog!”) What

about moving images?

For several years psychologists tested babies’ abilities

to recognize facial expressions in still pictures and movies, with mixed results. 20 Babies’ attention

can be captured by external stimuli at an early age, and they start to control

their focus and attention in the second month. By the seventh month, they are

responding accurately to pictures and moving-image displays. Yet it’s possible

that recognition starts much earlier. In ingenious experiments, Lynne Murray

and Colwyn Trevarthen set up TV cameras so that nine-week-old babies and their

mothers, stationed in different rooms, could see each other on monitors. The

experimenters wanted to record the interactions between them, as well as to vary

the timing of responses through pauses and replays. 20 Babies’ attention

can be captured by external stimuli at an early age, and they start to control

their focus and attention in the second month. By the seventh month, they are

responding accurately to pictures and moving-image displays. Yet it’s possible

that recognition starts much earlier. In ingenious experiments, Lynne Murray

and Colwyn Trevarthen set up TV cameras so that nine-week-old babies and their

mothers, stationed in different rooms, could see each other on monitors. The

experimenters wanted to record the interactions between them, as well as to vary

the timing of responses through pauses and replays. 21 21

Murray and Trevarthen’s

conclusions about the babies’ ability to

synchronize their responses with the mothers’ expressions has touched off

considerable debate and further experimentation. 22 That’s

not what matters for us as students of cinema. What’s relevant for us is

that the babies evidently did, in both real time and in tape delay, recognize

the moving images of their mothers. 22 That’s

not what matters for us as students of cinema. What’s relevant for us is

that the babies evidently did, in both real time and in tape delay, recognize

the moving images of their mothers.

What was methodology for Murray and Trevarthen

is substantive evidence for us. Very young babies could grasp the video image,

at least to some extent, as a representation of the most familiar person in their

lives. If babies do need to learn to recognize images, that learning seems to

take place very fast. In fact, we might better speak of elicitation rather

than learning: Given normal circumstances of human development, all that’s

needed is exposure to real-world persons, places, and things. Recognizing such

things in a moving-image display seems to come along for free. This account makes

sense in the light of evolution, as others and I have argued elsewhere. 23 23

Folk psychology: Success stories

The Big Clock.

There is a lot more to be said and studied about grasping

moving images as representations of real-world items, most saliently people,

but let me turn now to some matters of narrative that I’ve rethought since NiFF was

published.

Recognizing the contents of realistic images, I’ve

suggested, depends heavily upon our everyday perceptual abilities. Similarly,

filmic storytelling relies upon cognitive dispositions and habits we’ve

developed in a real-world context. That’s not to say that films capture

reality straightforwardly; as we’ll see, there are plenty of dodges and

feints. It’s simply

to say that ordinary perception and cognition ground what narrative filmmakers

do. On that foundation quite various, even fantastic, edifices can be built.

Central

to narrative psychology, I’ve come to suspect, is that elusive

thing called folk psychology. Folk psychology calls on “common sense”—our

everyday habits of attributing qualities, beliefs, desires, intentions, and the

like to ourselves and to people around us. There is considerable evidence that

many core procedures of common-sense reasoning are cross-cultural universals. 24 24

Consider “person

perception.” We tend to arrive at quick impressions

about those around us. At a glance we judge a person’s age, gender, race,

and personal attributes (Birkenstocks tell us one thing, bling another). From

their facial expressions, gestures, and voice, we judge their emotional states.

Our habits obviously transfer to stories, which present persons, or at least

person-like creatures like Daffy Duck. To follow the story we have to assign

the characters certain qualities. When introducing a character to us, a film

narrative simply hijacks our everyday capacities to build up a quick impression,

even (or especially) if that relies on stereotypes. That impression may be confirmed,

tested, or repudiated as the story develops, but our quick and dirty habits of

person perception provide a point of departure.

We also indulge in mind-reading.

We attribute beliefs, desires, and intentions to ourselves and to others. You

want a burger; you stop at a burger joint to get one. You act on your desire

based on beliefs about the world, most notably the belief that you can get a

burger at that joint. Maybe you did it all without explicit thinking, but in

retrospect you create a little story of coherent causes. We interpret others’ actions

the same way. If my friend says he wants a burger, and then I see him head for

a burger joint, I infer that he’s

acting on his beliefs and desires. Of course that inference can be overridden;

later I might find that he went to get a milkshake or to flirt with a waitress.

But even revising the inference requires the same schema. (Aha, he really

wanted a shake, or a date for tonight.)

From first to last, stories ask us

to apply what Daniel Dennett calls “the

intentional stance,” or what many would just call common sense. 25 At

the start of The Big Clock (1947), we see George Stroud slinking along

a corridor and avoiding a guard. He dodges behind a pillar and lets the guard

pass before we hear his voice-over: “Whew! That was close.” George

proceeds along a corridor, looking back nervously, as the voice-over continues: “What

if I get inside the clock and the watchman’s there?” 25 At

the start of The Big Clock (1947), we see George Stroud slinking along

a corridor and avoiding a guard. He dodges behind a pillar and lets the guard

pass before we hear his voice-over: “Whew! That was close.” George

proceeds along a corridor, looking back nervously, as the voice-over continues: “What

if I get inside the clock and the watchman’s there?”

From George’s

disheveled appearance and furtive movements, as well as the stream-of-consciousness

commentary, we have no trouble inferring his beliefs (he’s being hunted)

and his desire (to take refuge). We’ll accordingly

judge his future actions as advancing his intentions to escape detection, even

as his plans and his backstory will get specified further.

The centrality of

characters’ goals in classical filmmaking, of which

Kristin and I have made much on this site and in our research, fits our folk-psychological

tendency to pick out actions that fulfill desires in the light of characters’ beliefs.

The web of intentions can get very complicated—think of all the beliefs

and desires at play in The Godfather—but we’re very good

at tracking them because we expect that social situations exhibit what people

are planning to achieve. To bring babies back in, it seems that they too can

do mind-reading. One-year-olds attribute goals to robotic blobs that chirp and

move as if they had intentions. 26 26

There are enormous philosophical debates around the belief-desire

component of folk psychology. 27 Is

it truly explanatory, or just vacuous? But we don’t have to worry about

whether it’s true; what matters is that filmmakers invoke it and film viewers

follow their lead. Storytellers are practical psychologists, preying (usually

in a good sense) on our habits of mind in order to produce experiences. 27 Is

it truly explanatory, or just vacuous? But we don’t have to worry about

whether it’s true; what matters is that filmmakers invoke it and film viewers

follow their lead. Storytellers are practical psychologists, preying (usually

in a good sense) on our habits of mind in order to produce experiences.

Still,

there are important ways in which folk psychology leads us astray. Film exploits

those too.

Folk psychology: The downside

Daisy Kenyon.

In Everything Is Obvious* (*Once You Know the Answer),

Duncan J. Watts points out that one problem with classic belief-desire psychology

is that it is designed to explain individual behavior in concrete circumstances.

It doesn’t

scale up well to explain large-scale trends. A big event like the recent recession/

depression or the quieting down of violence in Iraq is easy to attribute to decisions

taken by Bush or Obama or Petraeus. In fact, the actual causes of such macro-events

are likely to be multiple, complex, and not visible to us. We tend to apply person-perception

habits to events that occur on a scale beyond that of individual action.

Watts’ book

is a contribution to “Wrongology,” the study of

our tendencies to overestimate our abilities, make simple logical errors, and

act inconsistently. The research area has its roots in the studies of heuristics

and biases conducted by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky. 28 Rationality,

as postulated by philosophers and economists, seems to be a rare gift. To take

a now-classic example: 28 Rationality,

as postulated by philosophers and economists, seems to be a rare gift. To take

a now-classic example:

Linda is 31 years old, single, outspoken, and very

bright. She majored in philosophy. As a student, she was deeply concerned with

issues of discrimination and social justice, and also participated in anti-nuclear

demonstrations.

Now, which is more likely?

Linda is a bank clerk.

Linda is a bank clerk and a feminist.

Most people say the latter

is more probable, although it can’t be. By adding

a second condition to the first, we make the second statement less likely. If

people reasoned according to formal logic, they would recognize this as a fallacy

of conjunction.

Likewise, the rational agent beloved of economists turns out to be motivated

by more than gain, as shown in the so-called Ultimatum

Game. Veronica has $100, while Betty has no money. According

to the rules, Veronica must offer Betty some of the money, and if Betty refuses

the split, neither player gets anything. Now if Veronica is a rational

agent, she ought to offer Betty as little as possible, maximizing her own gain.

And Betty, who starts off with zero dollars, should take even a measly $1, since

that leaves her better off than before. But in experiments conducted around the

world, the players in Veronica’s position tend to offer a fifty-fifty split.

More surprisingly, players in Betty’s position tend to reject offers of

less than $30, leaving both players with nothing.

Clearly social beliefs about

fairness are involved, along with some mind-reading on Veronica’s part

(If I offer her too little, she could get vindictive

and I could lose it all). Such factors have made the players’ behaviors

depart from strict economic rationality. Economists and psychologists who recognize

such “predictably irrational” pressures have created a discipline

called behavioral

economics.

So folk psychology has its own biases. Linda is said to

be a bank teller and a feminist because her profile fits a stereotype of feminists.

This is sometimes called the availability heuristic, the tendency to

apply the handiest schema to a situation. There is as well confirmation

bias, the

habit of looking only for evidence that supports the idea you’re leaning

toward. Once you’ve decided you’d really like an iPad, you’re

likely to overlook all the critical comments on the gadget in reviews. If you

believe in astrology, you’ll tend to remember the times that your horoscope

seemed to predict what happened to you and forget the more numerous times when

it failed to do so. Watts points out the reconstructive nature of memory as

another biasing effect. We tend to recast our recollection of what happened in

light of present circumstances.

One of my favorite biases is the primacy

effect, already discussed in

a blog

entry. Logically, the order in which items on a list are presented

should not affect how we think of them, but it does. Take Hong Kong supermogul

Leonard Ho’s

three daughters. Which of their names doesn’t belong with the other two?

Maisy, Daisy, and Pansy

Obviously, it’s

Pansy that’s out of step, since she doesn’t

rhyme with her sisters. But present them in reverse order:

Pansy, Daisy, and Maisy

…and the outlier is Maisy, who isn’t named

after a flower. The first item in a series tends to serve as a benchmark against

which we measure the ones that follow. I’ve always felt sorry that a brilliant

writer like Donald Westlake inevitably sits low and distant on paperback racks

while hacks like Jeffrey Archer benefit from the primacy effect.

Again and again,

narratives manipulate our psychological biases. For instance, once you’ve

decided that George Stroud in The Big Clock is fleeing

someone, everything he does tends to confirm that. The filmmakers exploit confirmation

bias. Likewise, the syuzhet layout relies on the primacy effect. The

film starts at a point of crisis, with George fleeing his boss’s goons.

The narration then flashes back to the beginning of the action, when George tried

to escape from Janoth’s overweening control by taking a long-promised vacation

with his family. The prologue warns us to watch for anything that will push Stroud

into danger, and we quickly expect that he will not go on the vacation. Had the

film begun with the more prosaic events that come earliest in the fabula,

we would not have been on the alert for Stroud’s plunge into a critical

situation. The prologue also signals the importance of the clock as a sinister

force and time as a motif through the film.

Alternatively, narratives can upset

our biases, as when we’re forced to

reevaluate a character about whom we formed firm initial impressions. We’re

obliged to do this with Danny Ciello in the closing moments of Prince of

the City. Here the film lures us with the primacy effect and the availability

heuristic (Catholic cop plagued by guilt decides to go straight). Confirmation

bias keeps our sympathy with him across the film; everything supports him as

righteous victim. But at the end a question emerges: might Danny be more corrupt

than we had thought? Meier Sternberg describes this as the “rise and fall

of first impressions,” and it often depends on the power of the primacy

effect. 29 At

the limit, a narrative film can try to avoid setting up any clear-cut first impressions,

as happens in “art films” like In the City of Sylvia. 29 At

the limit, a narrative film can try to avoid setting up any clear-cut first impressions,

as happens in “art films” like In the City of Sylvia. 30 30

Sometimes

one aspect of folk psychology can rescue another. For instance, Watts points

out that the Ultimatum Game doesn’t work the same way in all societies.

In experiments with the Machiguenga tribe of Peru, the moneyed partner tended

to offer only about a quarter of the total, and nearly all offers were accepted.

Both parties were being more “rational” by the economists’ standards.

But now belief-desire psychology kicks in. In Machiguenga society, the primary

bonds are with the immediate family, and strangers are of lower status. So the

moneyed partner felt little obligation to make a fair split, and the recipient

was happy with whatever was offered. Once we know this, the Machiguenga strategy

makes sense. 31 A

similar sort of thing happens in fantasy and science-fiction films. Once we learn

the unique laws and etiquette of Hogwarts or the Matrix, then familiar belief-desire-intention

patterns can lock in. 31 A

similar sort of thing happens in fantasy and science-fiction films. Once we learn

the unique laws and etiquette of Hogwarts or the Matrix, then familiar belief-desire-intention

patterns can lock in.

Folk psychology takes us beyond the purely perceptual level

I started with; it carries us into the realm of social intelligence. Mind-reading

requires us to detect, sometimes on very faint cues, what people are expressing

or signaling through their behavior. Elsewhere I’ve talked about this in

cases involving eye behavior—blinking and eyebrows,

in particular. But there’s much more to be done with the ways in which

cinema mobilizes our social intelligence in order to track a narrative. Sometimes

the narrative eases our task by making things redundant and clear; sometimes

the film throws up problems, making it hard to understand characters’ intentions

or reactions, as in the enigmatic veteran played by Henry Fonda in Daisy

Kenyon.

I found the concept of social intelligence especially useful

in explaining a form of cinematic storytelling that has become prominent since

the 1990s, what I called the network narrative. These “degrees of separation” tales

rely on our socially cultivated ability to track how people are connected to

others by proximity, kinship, or acquaintance, and how their different states

of knowledge create dramatic tension. 32 We

might as well call it the soap-opera effect. Again, however, such films are likely

to streamline the vast complexity of real-world social networks: the networks

in movies like Love, Actually and Sunshine State tend to be

simple and redundantly stated. More elliptically narrated films like Edward Yang

Dechan’s Terrorizers and Benedek Fliegauf’s Forest may

require more careful sorting and later rethinking of character connections. 32 We

might as well call it the soap-opera effect. Again, however, such films are likely

to streamline the vast complexity of real-world social networks: the networks

in movies like Love, Actually and Sunshine State tend to be

simple and redundantly stated. More elliptically narrated films like Edward Yang

Dechan’s Terrorizers and Benedek Fliegauf’s Forest may

require more careful sorting and later rethinking of character connections.

Another

aspect of folk psychology, crucial to narrative but neglected in NiFF,

merits more study: emotional response. In particular, some psychologists point

to the infectiousness of emotion. Babies share smiles with us, perhaps partly

as an evolutionary strategy to make us want to nurture them. (Even blind newborns

smile, so it can’t be something learned from watching others.) Some researchers

argue that our capacities for empathy depend on “mirror” cells tuned

to respond to others’ movements and emotion and allow us to register some

degree of mimicry. 33 Macaque

monkeys’ mirror neurons fire not only when they watch a mate grasping a

cup but also when they watch a film of a mate doing it. (More evidence that film

images require no special code-learning.) V. S. Ramachandran suggests that mirror

neurons could explain the fact that a mother sticking out her tongue provokes

her newborn baby to do the same, a presumably innate response. 33 Macaque

monkeys’ mirror neurons fire not only when they watch a mate grasping a

cup but also when they watch a film of a mate doing it. (More evidence that film

images require no special code-learning.) V. S. Ramachandran suggests that mirror

neurons could explain the fact that a mother sticking out her tongue provokes

her newborn baby to do the same, a presumably innate response. 34 If

assumptions about mirror neurons in humans turn out to be well-founded, we may

find that cinema, with its ability to capture gesture and the flickers of facial

expressions, is an ideal medium for triggering involuntary reactions (kinesthetic,

emotional), which can in turn can be recruited for narrative purposes. 34 If

assumptions about mirror neurons in humans turn out to be well-founded, we may

find that cinema, with its ability to capture gesture and the flickers of facial

expressions, is an ideal medium for triggering involuntary reactions (kinesthetic,

emotional), which can in turn can be recruited for narrative purposes.

Uncommon sources of common sense

Someone might suggest that this general line of thinking leads to observations

that are quite superficial. What viewer doesn’t see that George Stroud

in The Big Clock is trying to avoid the guards? I’d reply that

once we move beyond the moment to look at strategies of patterning at different

scales, we find things aren’t so obvious; that was the primary task of NiFF.

But I grant that our point of departure will seem very commonsensical. In fact, NiFF and

other things I’ve written have been charged with committing “common-sense

film theory.”

In one way that’s true. The humanities have in general

suffered from straining for the most far-fetched accounts of how art, literature,

and music work. In the literary humanities in particular, ingenious interpretations—often

relying on free-association, wordplay, and talking points lifted from favored penseurs—get

more notice than plausible explanations do. In various places I’ve

argued for naturalistic and empirical explanations as the best option we have

in answering middle-range questions, and even bigger ones like “How do

we comprehend movies?” Sometimes our answers will not be counterintuitive.

To say that looking at images recruits our skills of looking at the world will not surprise many people; but it is likely to be true. What’s

likely to be counterintuitive are the discoveries of mechanisms that undergird

perception. Would common sense predict that an object’s form, color, movement,

and spatial location are analyzed along distinct pathways in the visual system?

Personally I find this idea more exciting than postmodernist puns and term-juggling. 35 35

More

important, we can embrace common sense at a meta-level. Recognizing that it is

in play in narrative comprehension makes it something we need to analyze. We

can understand filmic understanding better if we recognize what’s intuitively

obvious, and then go on to ask what in the film, and in our psychological and

social make-up, makes something obvious. And those factors may not be

obvious in themselves. In other words, we may need a better understanding of

how common sense works, and how films play off it and play with it. That understanding

may in turn oblige us to accept empirical experiment, evolutionary thinking,

and neurological research—all of which most literary humanists find worrisome.

So

worrisome, in fact, that many don’t recognize naturalistic explanations

as being theoretical at all. For them, the only theories that exist are Big Theories,

and so efforts like the one I just mentioned are condemned as expressing a disdain

for or suspicion of theorizing tout court. But that objection, feeble

to start with, was blocked back in 1996 by the opening sentences Noël Carroll

and I wrote in our Post-Theory: Reconstructing Film Studies:

Our title risks misleading you. Is this book about

the end of film theory? No. It’s about the end of Theory, and what can

and should come after. 36 36

That

introduction and many of the pieces included in the volume float arguments for

theorizing as an activity that asks researchable questions and comes

up with more or less plausible answers—some commonsensical, some not, and

some probing what counts as common sense.

Ironically, just as filmic interpretation

is amenable to task analysis from a cognitive standpoint, a surprising amount

of Grand Theory seems to me to rely on the sort of folk-psychological schemas

and shortcuts that we find in ordinary life. But that’s a whole other essay.

1 :

The most influential, and still informative, account of one such code was Christian

Metz’s Grand

Syntagmatique of narrative cinema. See Metz, “Problems of Denotation in

the Fiction Film,” in Film Language: A Semiotics of the Cinema,

trans. Michael Taylor (New York: Oxford University Press, 1974), 108–146. Metz’s

more general consideration of cinematic codes is to be found in his Language

and Cinema, trans. Donna Jean Umiker-Sebeok (The Hague: Mouton, 1974).

2 : Peter L. Berger

and Thomas Luckmann, The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the

Sociology of Knowledge (New York: Anchor, 1967).

3 : On this Golden

Oldie of humanities lore, see Geoffrey Pullum, The Great Eskimo Vocabulary

Hoax and Other Irreverent Essays on the Study of Language (Chicago: University

of Chicago Press, 1991), 159–175.

4 : See Howard Gardner, The

Mind’s New Science: A History of the Cognitive Revolution (New York:

Basic Books, 1985).

5 : The phrase appears

in Jerry Fodor’s milestone 1983 book The Modularity of Mind (Cambridge:

MIT Press), 64–86.

6 : The phrase became

something of a slogan for the New Look school. See Jerome S. Bruner, Beyond

the Information Given: Studies in the Psychology of Knowing, ed. Jeremy

M. Anglin (New York: Norton, 1973).

7 : J. J. Gibson, Perception

of the Visual World (Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1974 [orig. 1950]; J. J. Gibson, The

Senses Considered as Perceptual Systems (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1966).

8 : On the Ames Room,

see William H. Ittelson, The Ames Demonstrations in Perception,

together with An Interpretive Manual by Adelbert Ames, Jr. (NewYork: Hafner,

1968). Go here for many videos employing the principles of the Ames Room. Interestingly, many of the voice-over commentators on these videos assume that

prior knowledge, expectations, and other cognitive factors influence perception,

indicating that New Look psychology remains a dominant paradigm for perceptual

researchers.

9 : Gibson made his

arguments about movies in The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception (Boston:

Houghton Mifflin, 1979), 292–302. See Joseph D. Anderson, The Reality of

Illusion: An Ecological Approach to Cognitive Film Theory (Carbondale: University

of Southern Illinois Press, 1996) and the articles collected in Moving Image

Theory: Ecological Coniderations, ed. Joseph D. Anderson and Barbara Fisher

Anderson (Carbondale: University of Southern Illinois Press, 2005). Had

I been more alert, I would also have had to consider arguments in John M. Kennedy’s A

Psychology of Picture Perception (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1974).

10 : Julian Hochberg

and Virginia Brooks, “Movies in the Mind’s Eye,” in In

the Mind’s Eye: Julian Hochberg on the Perception of Pictures, Films, and

the World, ed. Mary A. Peterson, Barbara Gillam, and H. A. Sedgwick, (New

York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 387–395.

11 : See my “Cognition

and Comprehension: Viewing and Forgetting in Mildred Pierce,” Poetics

of Cinema (New York: Routledge, 2008), 135–150. The chart in the essay was

printed inaccurately; an accurate one is at http://www.davidbordwell.net/books/poetics.php.

12 : See The

Way Hollywood Tells It: Story and Style in Modern Movies (Berkeley:

University of California Press, 2006), 63–71.

13 : Major examples

include Ed Tan, Emotion and the Structure of Narrative Film: Film as an Emotion

Machine (Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 1996); Torben Grodal, Moving Pictures:

A New Theory of Genres, Feelings, and Cognition (Oxford: Oxford University

Press, 1997), Carl Plantinga and Greg M. Smith, eds., Passionate Views: Film,

Cognition, and Emotion (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999),

Greg M. Smith, Film Structure and the Emotion System (Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press, 2007), and Carl Plantinga, Moving Viewers: American Film

and the Spectator’s Experience (Berkeley: University of California

Press, 2009).

14 : In another book,

I tried to show how theory-driven interpretations, like interpretations that

weren’t theory-driven, were amenable to cognitive and rhetorical analysis.

See Making Meaning: Inference and Rhetoric in the Interpretation of Cinema (Cambridge:

Harvard University Press, 1989).

15 : See my blog

entry, “Now you see it, now you can’t” for more discussion

of these trends.

16 : See William

Hudson, “Pictorial Depth perception in Subcultural Groups in Africa,” Journal

of Social Psychology 52 (1960), 183–208, and “The Study of the Problem

of Pictorial Perception among Unacculturated Groups,” International

Journal of Psychology 2 (1967), 89–107.

17 : See Stephan

Schwan and Sermin Ildirar, “Watching Film for the First Time: How Adult

Viewers Interpret Perceptual Discontinuities,” Psychological Science 21

(2010): 970–976. Online access is at http://pss.sagepub.com/content/21/7/970.abstract.

18 : Paul Messaris, Visual

Literacy: Image, Mind, and Reality (Boulder: Westview, 1994), 165.

19 : Julian Hochberg

and Virginia Brooks, “Pictorial Recognition as an Unlearned Activity: A

Study of One Child’s Performance,” in In the Mind’s Eye,

64.

20 : For a review

of early experiments, see Charles A. Nelson, “The Perception and Recognition

of Facial Expressions in Infancy,” in Social Perception in Infants,

ed. Tiffany M. Field and Nathan A. Fox (Norwood, NJ: Ablex, 1985), 101–125. Later

experiments in infant cognition are considered in the light of “folk” theories

of mind, physics, and the like, in Steven Pinker, How the Mind Works (New

York: Norton, 1997), Chapter 5.

21 : Lynne Murray

and Colwyn Trevarthen, “Emotional Regulation of Interactions between Two-month-olds

and Their Mothers,” in Social Perception in Infants, ed. Field

and Fox, 177–197. Ellen Dissayanake has proposed a fascinating theory of the

origins of art based in mother-child interactions; see Art and Intimacy:

How the Arts Began (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2000).

22 : See, for example,

Phillipe Rochat, Ulric Neisser, and Viorica Marlan, “Are Young Infants

Sensitive to Interpersonal Contingency?” Infant Behavior and Development 21,

2 (1998): 355–366.

23 : See Anderson, Reality

of Illusion, Chapters 3–5; see my “Convention, Construction, and Cinematic

Vision,” in Poetics of Cinema, 57–82.

24 : See for a summary

Donald E. Brown, Human Universals (Philadelphia: Temple University Press,

1991), 130–140.

25 : Daniel C. Dennett, The

Intentional Stance (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1987).

26 : Alison Gopnik, The

Philosophical Baby: What Children’s Minds Tell Us about Truth, Love, and

the Meaning of Life (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2009), 98.

27 : To get the

flavor of some of the debates, see Barry Loewer and Georges Rey, ed., Meaning

in Mind: Fodor and His Critics (Cambridge: Blackwell, 1991), especially

Daniel C. Dennett, “Granny’s Campaign for Safe Science,” 87–94

and Fodor’s reply: “The enormous practical success of belief/desire

psychology makes a prima facie case for its approximate truth” (277). By

the way, I should make it clear that I use “intentions” in this paper

in a nontechnical sense, not in the philosophical sense, as in Fodor’s

references to “intentional states.”

28 : See Daniel Kahneman,

Paul Slovic, and Amos Tversky, eds., Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics

and Biases (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982).

29 Meir Sternberg, Expositional

Modes and Temporal Ordering in Fiction (Bloomington: Indiana University

Press, 1978), 99–102. More generally, a great deal of Narration in the Fiction

Film, including its focus on curiosity, suspense, and surprise, is indebted

to Sternberg’s book, a trailblazing work of modern narratology.

30 : I discuss Prince

of the City’s narrational tactics a little bit here and

a crucial sequence of In the City of Sylvia, at greater length,

here.

31 :

Duncan J. Watts, Everything Is Obvious* (*Once You Know the Answer): How Common

Sense Fails Us (New York: Crown, 2011), 12–13.

32 : “Mutual

Friends and Chronologies of Chance,” in Poetics of Cinema, 189–250.

33 : See Giacomo

Rizzolatti and Corrado Sinigaglia, Mirrors in the Brain—How Our Minds

Share Actions and Emotions , trans. Frances Anderson (New York: Oxford University

Press, 2008) and Marco Iacoboni, Mirroring People: The New Science of How

We Connect with Others (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2008)

34 : V. S. Ramachandran, The

Tell-Tale Brain: A Neuroscientist’s Quest for What Makes Us Human (New

York: Norton, 2011), 121–128.

35 : See Margaret

Livingston and David Hubel, “Segregation of Form, Color, Movement, and

Depth: Anatomy, Physiology, and Perception,” Science 240 no 4853

(6 May 1988): 740–749. Available at http://www.sciencemag.org/content/240/4853/740.abstract.

36 : “Introduction,” Post-Theory:

Reconstructing Film Studies, ed. David Bordwell and Noël Carroll (Madison:

University of Wisconsin Press, 1996), xiii. More generally, much of what I’ve said in this online essay was said more pointedly in Carroll’s pioneering 1985 article, “The Power of Movies.” See Carroll, Theorizing the Moving Image (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 78–93. |

|